The kumbaya party: George W. Bush has united the Democrats. Now it’s up to John Kerry and John Edwards to translate that unity into victory. AMONG THE EVER-shifting blocs and factions that make up the Democratic Party, unity is an elusive and fleeting thing, more a goal than a destination, a theory rather than reality. So perhaps the thousands of Democrats gathered in Boston this week should pay tribute to the man who brought them together.

No, not John Kerry. Unlike Bill Clinton, who obliterated party divisions through the sheer force of his personality and his prodigious political gifts, the Massachusetts senator inspires respect, not passion. Rather, the Democrats are joining as one this week because of George W. Bush, reviled among the party faithful as surely the worst president since Richard Nixon, if not James Buchanan. Few speechmakers have resisted the urge to observe that Bush — true to his 2000 campaign promise — has, for the Democrats at least, been a uniter, not a divider.

On the left, you hear it from Fahrenheit 9/11 director Michael Moore, telling a crowd of young Howard Dean supporters on Tuesday to vote and work for Kerry rather than Ralph Nader, and never mind that Kerry voted for the war in Iraq. “One thing about Kerry,” Moore thunders. “He will not invade a country the way George W. Bush did.” You hear it from Arianna Huffington, speaking at a Sunday tribute to the late senator Paul Wellstone, telling the progressives who have packed the Old West Church, “When your house is on fire, it’s not the time for remodeling.” You even hear it from far-left Boston city councilor Chuck Turner, who, at the Wellstone event, pronounces himself a Kerry supporter even though he thinks the senator “isn’t prepared mentally, emotionally, spiritually to be the president we need.”

You hear it from the party’s moderate wing as well. Following an event on Tuesday at Radius, a stylish restaurant in the Financial District, Simon Rosenberg — president and founder of the centrist New Democrat Network, an outgrowth of the better-known Democratic Leadership Council — told me, “I think all wings of the party are flying this week. Moderates and liberals are speaking with a single voice because I think we really are unified. There is no evidence of left-right fighting in the Democratic Party right now. I credit John Kerry. And George Bush.”

Yet there are limits to the kumbaya approach, limits that could be exposed and exploited by the Republicans’ relentlessly negative attack machine. Rosenberg, for instance, insists that it is possible to appeal both to the Democratic base of liberal voters and to swing voters who consider themselves moderate. So I asked him — coming up with the most crudely simplistic example I could think of — how to reconcile liberal opposition to the death penalty with the more mixed view held by those in the middle. Rosenberg’s solution: change the subject. “It’s not a zero-sum game, because undecided voters do not make up their minds on a single issue,” he said, explaining that the Democrats should focus on three broad areas: security, the economy, and health care. Sound advice, perhaps, but it’s doubtful that Karl Rove will play along.

Which is why much is riding on Kerry’s prime-time speech on Thursday, the last night of the convention. An oft-repeated observation this week is that polling data show as many as 40 percent of potential voters know very little about him, even if they have expressed a strong interest in voting for him. The proverbial most-important-speech-of-his-life is the best opportunity he’ll have to introduce himself to the American people, to show some warmth and strength, and to reach out to his party’s moderate and liberal wings while simultaneously framing an appeal to independents.

“He hasn’t really made the sale yet, which puts tremendous pressure on Thursday night. He’s got to be really good,” says Robert Kuttner, co-editor of the liberal American Prospect magazine and a syndicated columnist.

The conventional wisdom is that the country remains as evenly divided as it was four years ago, when the contest between Bush and Al Gore ended in a virtual dead heat. Thus, the easy call is to predict that the 2004 campaign will yield a narrow win for Kerry or Bush. But with Bush’s job-approval ratings stuck below 50 percent, and with Democratic-leaning organizations registering thousands of new voters, there is a sense that Kerry might be able to win decisively, and return one or both branches of Congress to Democratic control as well.

“We are clearly on the verge of a major Democratic victory in the presidency, in the Senate, and in the House,” Congressman Barney Frank shouted into the microphone during a party for the Massachusetts congressional delegation on Monday at the Moakley Federal Courthouse. (Frank also warned that if the Democrats do win, “we will have inherited a very difficult situation,” with “no friends and no money.”)

Can Kerry take advantage of the opportunity that has been handed to him? Bill Clinton’s rousing speech on Monday night suggests what a long way Kerry has to go. Clinton oozed dynamism and charisma, masterfully talking about his own new wealth as a way to criticize Bush’s tax cuts for the wealthy, and about his own (and Bush’s and Dick Cheney’s) efforts to stay out of Vietnam as a way to praise Kerry’s military heroism.

Kerry couldn’t have asked for a better tribute. But on Thursday — and for the three months remaining in this seemingly endless presidential campaign — he’s got to do as well on his own.

JOHN KERRY shares something in common with Al Gore, and that’s not meant as a compliment. Whereas Bill Clinton glosses over differences and contradictions so effortlessly that he can make you believe they never existed, with Gore and Kerry you can hear the gears turning and the levers clanking as they seek to reconcile and appease various groups of voters.

Gore would pander, boasting of his tobacco-farming experience even after his sister had died of lung cancer. Kerry fudges, telling a crowd that he voted for $85 million in reconstruction money for Afghanistan and Iraq before he voted against it, and offering so many shades of gray that it can be hard to tell where he stands. He’s not a flip-flopper, as the Republicans would have you believe. But on too many issues he’s what used to be called a mugwump — that is, someone with his mug on one side of the fence and his wump on the other, shifting his emphasis depending on the circumstances and the audience. As political shortcomings go, this does not rank with, say, launching an unnecessary war that has cost nearly 1000 American lives. But it is a shortcoming nevertheless, and the Republicans have already spent tens of millions of dollars in negative advertising to exploit it.

Or consider the issue of same-sex marriage. As is his wont, Kerry has staked out a highly nuanced position. His voting record on gay rights is generally excellent. In 1996 he voted against the loathsome Defense of Marriage Act, which passed anyway and was eagerly signed by Clinton, then running for re-election. More recently Kerry opposed a constitutional amendment, supported by Bush, that would ban same-sex marriage. Yet Kerry himself says he opposes gay marriage, though he supports civil unions that would provide all the rights, benefits, and protections of marriage.

Which leads to folks like Bennett Lawson, a young gay man from Chicago, supporting Kerry at least in part because he doesn’t believe him. I met Lawson outside a gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgender caucus meeting at the Sheraton. An aide to Chicago-area congresswoman Jan Schakowsky, Lawson had volunteered to work at the convention doing outreach to the GLBT community. On the day we talked, that outreach consisted mainly of making sure no one grabbed any of the bag lunches that had been prepared for caucus-goers.

I asked Lawson whether he was put off by Kerry’s opposition to gay marriage. “He’s running nationwide in a country that is not exactly comfortable with gay marriage,” Lawson replied. “His record is very, very strong on gay issues. Every good liberal has to moderate things in order to run nationwide — or, in Illinois, to run statewide — but his record really speaks for itself.” I told Lawson that he sounded like he didn’t believe Kerry when he says he genuinely opposes same-sex marriage. “No,” he replied, laughing. “You know what? I don’t.”

I also briefly interviewed California senator Barbara Boxer as she was running off to an engagement. She had just finished speaking to the GLBT caucus, which greeted her with raucous applause. So I was surprised when she told me that her position on gay marriage was precisely the same as Kerry’s: civil unions and domestic partnerships with all the rights of marriage, yes; marriage itself, no. I asked her whether she was concerned that the Bush campaign would use the enthusiasm of Kerry’s gay, pro-marriage supporters against him. “If they want to do that, I think they would be making a terrible mistake,” she said. Yet the dilemma is clear enough. Lawson — and no doubt many other gay activists — firmly believes that politicians such as Kerry and Boxer are winking in their direction when they claim that they oppose gay marriage. That is exactly what the Republicans are saying as well.

By striving not to be a risk-taker, Kerry is taking a different kind of risk — that he will suffer all of the political downside associated with supporting gay marriage, but only some of the upside. The Republicans are going to paint Kerry as a gay-marriage advocate regardless of what he says. But by continuing to assert that he doesn’t support same-sex marriage, he may cause some gay and lesbian voters who decide to stay home on Election Day. Or vote for Ralph Nader.

It’s that kind of nuanced — or overly nuanced — view that might protect Kerry from feeling the heat that comes with taking strong stands, but that also keeps him from inspiring much devotion among his supporters. After Senator Ted Kennedy delivered a bellowing, voice-cracking endorsement of Kerry on Tuesday night, Boston Globe columnist Joan Vennochi, appearing on WBUR Radio (90.9 FM), observed that Kennedy has been a staunch critic of Bush’s Iraq policy, referring to it in his speech as a “misguided war” — a position that Kerry can’t quite bring himself to embrace.

At a pre-convention forum last Thursday in the Mary Baker Eddy Library, Christian Science Monitor political reporter Liz Marlantes attributed Kerry’s caution to his years in the Senate, and to the experience all veteran politicians have with getting burned for things they have said. “The danger,” Marlantes said, “is that they come across as not having a strong position on anything.”

In most elections, that might be a prescription for success. But there are signs that 2004 isn’t like most elections.

LAST SUNDAY, the results of a New York Times/CBS News poll showed that this is shaping up as an unusual campaign. Fully 79 percent of those surveyed reported that they had already made up their minds, compared with 64 percent in July 2000. Bush’s job-approval rating was 84 percent among Republicans and 16 percent among Democrats, the widest such gap ever recorded in an election year. What this means is that the electorate is deeply divided, with fewer undecided voters than is typical. It also likely means that Kerry and Bush will each get a smaller bounce out of his national convention than is typical. (Not that such bounces mean much. You may recall that Michael Dukakis came out of his convention in 1988 with a huge lead over George H.W. Bush.)

Reinforcing that are recent findings by the Vanishing Voter Project, at Harvard’s Kennedy School. According to a recent survey, just 28 percent of respondents said they planned to watch some or most of the Democratic National Convention, down from 31 percent four years ago. Yet 50 percent said they had paid at least some attention to the presidential campaign, nearly double the percentage four years ago. So yes, Kerry’s speech will be important, as was Clinton’s and Kennedy’s and that of Kerry’s running mate, John Edwards, and of his wife, Teresa Heinz Kerry. But there’s a long slog ahead.

Thomas Patterson, the director of the Vanishing Voter Project, says that with Bush’s low approval rating, Kerry should come out of the convention with a lead of six to 12 points, a considerable improvement over the dead heat he’s been in since wrapping up the nomination in March. The message, Patterson says, should be that “this guy may not be the best thing since sliced bread, but damn it, he’s a good alternative, he’s not a weak alternative.” Patterson adds: “I think what people are looking for is strength. Bush projects strength.” But he believes that, given Bush’s poor numbers, Kerry should be able to build a lead within a week to 10 days that Bush will have a hard time overcoming.

At a time when the electorate is so divided, and the undecided vote is so small, Kerry might be tempted to play to the base — to hammer away at traditional Democratic issues such as abortion rights and labor concerns in order to drive up turnout among Kerry supporters as much as possible. Certainly that’s what the Republicans are doing by attempting to use gay marriage as a way to accomplish their goal of increasing turnout among evangelical Christian voters by three million over the last presidential election.

But such a strategy is neither necessary nor smart, according to Harold Ickes, a former top aide to Bill Clinton who’s now chief of staff of America Coming Together (ACT), a political-action committee that plans on spending $125 million to bring Democratic-leaning voters to the polls this fall. ACT is focusing its efforts on 17 swing states, such as Pennsylvania, Ohio, Arizona, Florida, Maine, and New Hampshire. The goal, Ickes said at a briefing at the Four Seasons Hotel, is to appeal to two groups of voters. “You can’t win with base alone, and you can’t win with swing alone,” he said. Afterward, he told me that though “Kerry is still very hazy in the minds of most voters,” he’s not concerned for one simple reason: Bush is energizing the base of not just the Republican Party, but of the Democratic Party as well.

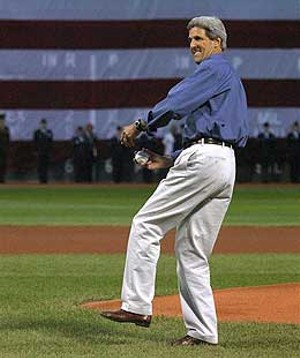

Which brings us back to George W. Bush, the Great Uniter. On Monday, I had a chance to ask two Massachusetts congressmen — Ed Markey and Bill Delahunt — what Kerry most needs to accomplish this week. Their answers differed. Markey said Kerry needs to stress national security, to show that he’s a “tough guy.” Delahunt believes that Kerry needs to do more things like attend Red Sox games so that people “are comfortable with him.”

Both, though, agreed on what Kerry will face as soon as the convention is over: vicious, negative attacks by the Republicans. “We have to call them for what they are. When they lie, we shouldn’t be pleasant,” said Delahunt. Added Markey: “They’re going to go totally negative. If he [Kerry] gets hit, he’s going to hit back.”

The national convention is a curious institution. It hasn’t chosen a presidential candidate, or even made a significant decision, in several decades. It’s potentially a great way for the parties to introduce their candidates, but the network news divisions have cut way back on coverage, to just three hours a week, because of the utter lack of news. Mainly they’ve become an obsession for political and media junkies who watch them on one of the cable news channels or C-SPAN. Given the security hassles involved in running a convention post-9/11, it is not inconceivable that they will be drastically scaled back before 2008 rolls around.

John Kerry and John Edwards will leave Boston with a united Democratic Party behind them and a modest bump in the polls. Still to come: the withering attacks of Karl Rove and company, and the televised presidential debates.

A great speech on Thursday will get the Kerry-Edwards ticket off to a good start. But there’s still a long way to go.

Dan Kennedy can be reached at dkennedy@phx.com. Read his continuing coverage of the Democratic National Convention on Media Log, at

BostonPhoenix.com.