'The Kindness of Strangers'

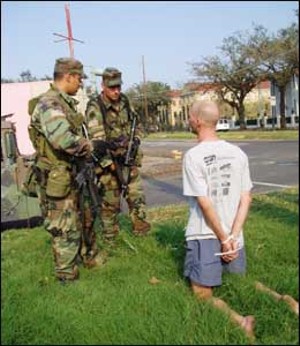

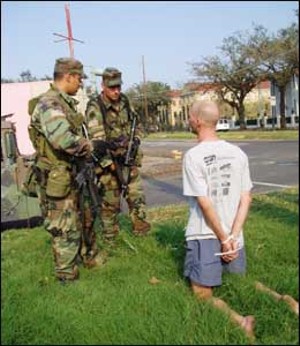

Ben Fenwick/Oklahoma Gazette

Members of the Oklahoma National Guard in New Orleans' Garden District detain a man suspected of looting.

“They told me to take a streetcar named Desire, and then transfer to one called Cemeteries and ride six blocks and get off at — Elysian Fields!” —Blanche DuBois, “A Streetcar Named Desire”

NEW ORLEANS — “Search and rescue! Stand back from your front door! Search and rescue!” Staff Sgt. George Ramirez of Altus shouted through the megaphone. His characteristic southwestern Oklahoma twang making “rescue” sound like “res-keeeewwww.”

Michigan Undersheriff Dave Fowler gunned the motor and the boat crashed through the front door at the house on Pleasure Street.

Fowler cut the motor. Ryan Sutton, a deputy under Fowler, stood at the front of the boat and grabbed the eaves of the partially submerged house, holding fast to keep the boat from floating away. The Michigander leaned down and peered into the smashed, half-sunken foyer.

“Search and rescue! We are here to help! Make some noise! Search and rescue!” Ramirez shouted again.

Silence.

“OK,” said New York Emergency Medical Technician Chris Lyons. “Let’s go in.” Ramirez set aside his M-16 and clambered up onto the balcony with Lyons. Sutton started to follow.

“Only two on that balcony,” ordered Fowler. Sutton stayed back. He handed the M-16 to Ramirez and the fire axe to Lyons.

Lyons took the axe, and, covered by Ramirez, hacked the door open. The men entered, emerging minutes later shaking their heads. All clear.

“Paint it,” ordered Fowler.

Sutton tossed Lyons a can of orange spray paint. The EMT sprayed an “X” on the side of the house, with the date, the search unit’s designation and a “zero” for zero persons or bodies found. Then the men climbed back into the boat and the unit pulled away from the house, motoring to the next on Pleasure Street. The crew repeated this activity throughout the day, searching for the living amid the debris of the Big Easy.

The crew and their flat-bottomed steel boat were part of an ad hoc flotilla. Other search and rescue volunteers came from Ada with the Chickasaw Nation, dodging bullets alongside members of the Oklahoma National Guard’s 45th Infantry Brigade, the Thunderbirds, which provided security.

For days, the Chickasaw team trolled through sunken neighborhoods, braving not only snipers, but the churning, poisonous water that roiled around them, black with oil from sunken cars, sewage and disease from rotting bodies. Just as dangerous was what the water hid — downed lines to tangle, injure or drown rescuers. Fences, whether barbed wire or the spiked wrought-iron for which New Orleans is famous, lurked beneath the black water, waiting to tear out the bottom of a boat or a boot.

As of Sept. 9, the crew had rescued scores of people trapped in their houses, but the numbers were quickly falling off. Two days before that, they’d gotten more than a dozen. Yesterday … one. That person, an elderly woman, would have died after another day, said Safety Officer Charles Scott from the Chickasaw unit.

“We pulled one out yesterday,” Scott said. “She was naked and in the water the whole time. She just lost it. She was just barely alive. She was gone, mentally.”

Other factors made getting to the victims difficult, Scott said.

“A lot of these houses have bars on the windows. We have a lot of trouble getting in so you know they couldn’t get out,” Scott said. “A lot of them crawled up in the attic. Do you know how hot it gets in an attic? That sun beatin’ down on it all day … it’s hotter ’n hell.”

By noon the temperature rose to 100 degrees on this search, with the humidity percentage about as high. The heat broiled the body and dulled the mind. Mistakes dogged Fowler’s crew. At one house they left the axe, only to have to turn around and get it. At a duplex from which the water had receded only inches, the men wore themselves out beating down the burglar bars on the doors. Ramirez entered one side, Lyons the other side. Inside, Ramirez walked through a door into Lyons’ side and spooked Lyons, who shoved the door into the sergeant’s face and cut him.

“Hey! I hit George!” Lyons called out to the boat. Ramirez emerged with the slight cut on his cheek near his eye. Someone tossed up some iodine. Any cut, however slight, had to be treated on the spot because of the contaminated surroundings. Lyons apologized. Ramirez laughed it off. The boat moved on.

The signs in the area poked out of the flood with now-ironic street names. Pleasure. Arts. Humanity. Music. Treasure.

They found the dead man tied to an interstate sign on Elysian Fields Avenue.

A famous street in both New Orleans and in the Tennessee Williams play set there, “A Streetcar Named Desire,” Elysian Fields is also the mythical Greek version of heaven, the fields of the noble dead. In New Orleans, Elysian Fields leads through a largely poor-to-middle-class black neighborhood, filled with shotgun houses, many with bars on doors and windows. Whoever tied the man to the sign did not collect him this day, or for apparently days thereafter, according to published reports. Another body, wrapped in a blue tarp, floated nearby.

“It’s unreal, isn’t it?” Ramirez said. “I’ve been working supplies since I hit the ground. This is my first time out. It’s a good thing, since the number one thing in my job is to take care of the troops. Sometimes it gets monotonous. This puts me back in perspective, of why I do my job.”

After sighting the body, Fowler’s crew looked through a couple more houses, then Fowler called it a day and the crews motored back to the retrieval point. On the way to the Elysian Fields on-ramp, where waited the trucks to carry out the boats, the crew hit a submerged truck and broke its windshield. Later, Fowler apologized.

“I’m sorry we lost our professionalism at the end, there,” Fowler said.

Beyond their fatigue lay something more than lapsing professionalism. A sense of despair settled into the crew. Two dead bodies, one probable dead body in a bad-smelling house that the crew elected not to enter, and no living evacuees. Most in search and rescue know that finding someone alive in a survival situation past 10 days is a miracle. This would be this crew’s last outing.

The trip through the empty interstate drove home the scale of the disaster. Around them, the dead, flooded city stretched as far as the eye could see … watery rooftops, cars barely visible beneath the murk, roads leading into black water and ruined businesses jutting out of the muck.

The hurricane-blasted Superdome loomed above their tiny convoy like a dark relic.

The Thunderbirds take wing

“Only Poe. Only Mr. Edgar Allan Poe could do justice to it. What are you doing in that horrible place?”—Blanche DuBois, “A Streetcar Named Desire”

Oklahoma Gov. Brad Henry issued the alert when the levees broke. The 45th Infantry Brigade was going to New Orleans.

New Orleans is not the first darkened horizon glimpsed by the Oklahoma Guard. The 45th formed in the Twenties, adopting their familiar Native American Thunderbird symbol in the late Thirties on the eve of World War II. In that war, the Thunderbirds landed at Anzio and held a beachhead despite daily shelling for months from Nazi gun emplacements. At the end of the war, the 45th liberated the infamous concentration camp at Dachau. They later fought in Korea, then did not deploy into the field for more than 50 years. In 2004, the 45th entered the conflict in Afghanistan, and, despite numerous pitched battles, returned home a year ago without one life lost in the unit.

In the initial hours of Hurricane Katrina, after the eye of the hurricane missed New Orleans by 15 miles to the east Aug. 29, Oklahoma sent two Blackhawk helicopters to assist in search and rescue. It became quickly apparent that the scale would call for much, much more. Damaged in the hurricane was the Louisiana National Guard’s command center, which flooded. Local Guard headquarters had to relocate.

So did the 45th. As footage of flooding and looting, and stories of rape and murder exploded on the national networks, the Oklahoma Guard first dispatched two C-130 transport planes to the area carrying a Quick Reaction Force of armed soldiers, who were among the first guardsmen to enter the Superdome.

Maj. Gen. Harry M. Wyatt III, the adjutant general for the state of Oklahoma, said that such expediency, though it probably saved many lives, may soon be a thing of the past.

“These (the C-130s) are the airplanes that the Air Force and the BRAC (Base Realignment and Closure) Commission has recommended leave the state of Oklahoma,” Wyatt said at a press conference recently. “I want you to think about how impossible this mission would be and how difficult it would be to quickly react without that capability. I think we are making a big mistake by shipping these planes out of the state’s Air National Guard and out of the governor’s reach as commander in chief.”

By Aug. 31, Brig. Gen. Myles Deering, the commander of the 45th Infantry Brigade, moved a command center into New Orleans and established his headquarters at a looted Wal-Mart Supercenter on Tchoupitoulas Street, near the city’s storied Garden District. Soon Deering commanded all the military units in New Orleans parish, more than 15,000 troops. Called Task Force New Orleans, the command includes the 82nd Airborne, the First Cavalry and the Marines of the 24th Expeditionary Unit — all active duty units, not National Guard.

“Because he was one of the first general officers on the ground in New Orleans, other than the Louisiana National Guard, and because he was well organized and supplied with capability and equipment funneled to him from Oklahoma, he was given command of this task force,” Wyatt said. “This is an Army National Guard commander in charge not only of National Guard but active duty forces. That doesn’t happen a lot.”

The 45th itself took control of the Garden District, some of the most expensive real estate in the country. Patrols began right away, sometimes hand in hand with the New Orleans police, sometimes with 45th units alone. Occasionally shots were exchanged, but with inconclusive outcomes. No 45th soldiers as of this writing were yet injured from gunfire. Soon, however, such incidents grew rare. Looters shrank from uniformed, armed soldiers walking the streets.

After the 45th established order, the scale of the disaster sank in, Deering said.

“Obviously the worst damage is the flooding. It’s the worst I’ve ever seen. Although it’s not total, the flooding is in some places 20-foot deep inside the city,” Deering told Oklahoma Gazette Sept. 9.

Deering said the looting troubled him most.

“The devastation here … it’s one thing to see the hurricane damage. Then the flooding with the levees breaking through. But to see the element that destroyed their own city by looting and plundering … that definitely amazes me,” Deering said.

Deering described the emptiness of the city, of driving through the quiet streets of the Garden District, past antebellum mansions without a light or a sound coming from them.

“I tell you I see some eerie sights. Driving down St. Charles Avenue in the middle of the night, with all those million-dollar homes, and it’s pitch-black … it’s like a ghost town,” Deering said.

‘The lizard, the boa, the dog and the guy’ “Whoever you are — I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” —Blanche DuBois, “A Streetcar Named Desire”

Even before the floodwaters started receding, the 45th and elements attached to them started bringing in survivors. Some didn’t want to come. At first Deering and others were told that they’d be used for mandatory evacuation of the city. But as time stretched on, Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Blanco vacillated. Nevertheless, the Thunderbirds and others plowed on.

One effort attempted to take evacuees who were afraid to give up their pets. Many city residents, when they heard of pets being seized or even euthanized as part of the evacuation effort, refused to leave their homes. So, elements of the 45th teamed with animal-welfare specialists and medical personnel to rescue all.

During one such effort, the 45th dispatched armed soldiers guarding two trucks that carried rescuers into the fringes of the French Quarter. As the trucks skirted the floodwaters, passing the famed and now boarded-up Tipitina’s club, the medical personnel led soldiers house to house, to known holdouts in an attempt to get them to leave.

The first evacuee encountered by the unit was Blaine Barefoot, a former Oklahoman and a member of the Sac and Fox. Barefoot said he’d only moved to the city recently after leaving Oklahoma.

“I had a great gig as a banquet chef at the Oklahoma City art museum, right?” Barefoot said. “They asked me why I was leaving. I said, ‘Ever been to the Gulf Coast? Once you go, you won’t never come back.’ Dude, I won’t ever say that to anybody again.”

Barefoot said he holed up in his apartment with a few crates of military rations (MREs, or meals ready to eat) and waited out the storm. His area was one that didn’t flood. He found innovative ways to get by.

“Man, I had MREs up the butt,” Barefoot said. “I probably still had 150 gallons of water in my apartment. Two hot water heaters — that’s 80 gallons apiece right there. A lot of people didn’t realize it, man. I’d say, ‘You got a hot water heater?’ They’d say, ‘Yeah, man.’ Well, that’s 40 gallons of water right there.”

Determined to stay, he heard that the evacuation would soon be mandatory, and decided to surrender.

“It’s a shame about the forced evacuation. But if y’all are going to come take me out by force, well, that’s no way to go. So I’m outta here,” Barefoot said.

Soon the soldiers collected Barefoot and about 15 other evacuees. At one point, the convoy waited while medical personnel dealt with a man with a number of pets and a female addict who had started into withdrawal, begging for methadone. The small convoy idled while a military ambulance took away the addict and then loaded the man’s unusual menagerie.

“We’re just waiting for the lizard, the boa, the dog and the guy — in that order,” explained New York registered nurse Greta Jugl, who had headed up the rescue effort that day. “I’m very pleased with how many people we got. There was a rumor that at the (New Orleans) Convention Center they would make them let their animals go. Maybe it wasn’t a rumor. So everybody was fearful and hiding. But when they saw me, a girl with a stethoscope, they trusted me.”

By the end of the mission, the soldiers brought about 20 evacuees to the processing center near headquarters — along with their pets.

The water’s edge

“You just came home in time for funerals Stella, and funerals are pretty compared to deaths. How did you think all that sickness and dying was paid for? Death is expensive, Miss Stella.” —Blanche DuBois, “A Streetcar Named Desire”

Pvt. Chris Reed whipped the Humvee to the right and skidded out onto Harmony Street, following directions from a black helicopter.

“Silver SUV, going house to house,” he explained, speeding along the littered streets, empty of humanity. “Looter.”

The Kiowa helicopter had been hovering overhead while a squad of soldiers from the 279th Infantry, out of Tulsa, patrolled the north end of the Garden District, tracking the edge of the receding black floodwaters. The soldiers speculated the copter’s purpose until they got the call.

At St. Charles Avenue, they caught up with the man the Kiowa tracked. Another contingent of the 45th headed him off and blocked him. Soldiers surrounded the man — a white man who appeared to be in his 30s. They cuffed him with plastic zip-cuffs and forced him to kneel.

“It’s mine, it’s mine. I can show you. I’ve got my name on it,” the man pleaded to the huddled soldiers going through his billfold. He had a large number of $100 bills.

Sgt. 1st Class Eric Ranney, whose unit chased the suspect into the checkpoint, turned and shouted at him.

“Turn around and face the pole! I said turn around or I’ll frickin’ dog-tie you, feet and hands,” Ranney said.

The man shut up and turned to the pole.

Ranney, of the 279th Infantry out of Tulsa, recognized the suspect. About 15 minutes earlier, he and his soldiers inadvertently followed him on a mission to check the receding water levels. The man got out, waved a passport, and shouted “ASPCA (American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals)! ASPCA!” The ASPCA traveled regularly into the floodwaters, rescuing stranded pets. The man seemed credible.

Except that now the back of the SUV was filled with stuff that hadn’t been there before. Ranney said the helicopter watched the man enter several houses, removing items, after his patrol passed.

“This is the guy who came running out representing himself as ASPCA,” Ranney noted. “They (the helicopter) found him, called it in, and we were in pursuit. They caught him at this traffic checkpoint.”

“We heard the report of the silver SUV and just came along,” said Lt. Adam Cortright, of Tulsa. “Heard about it and happened to catch a glimpse of him driving by.”

As the days proceed in the New Orleans saga, it’s likely such incidents will be repeated. People will come into the city, and who is to know whether they actually belong to the houses they enter?

“It appears that people are trying to get back in the city and it can only hamper efforts to get them back quicker,” Deering said.

In the meantime, as the waters recede, other questions will mount. What will former residents do when they return? How can they live in a contaminated house? What will happen to their property? Who will pay the estimated $200 billion tab? And yet, how can the city live again, with 80 percent of its people gone away?

The darkest question of all … how many died … may be answered soon as the waters recede.