L.J. Ebner loves the Boston Red Sox - fiercely, and with a strong sense of obligation. He's certain the team wouldn't have swept the World Series if he'd neglected to wear his Red Sox shirt and cap while watching their games. He tried hard not to dwell on negative thoughts during the post-season, out of fear it would affect the team's performance. He's even taught his dog, Bella, to give him a high-five when he says, "Go Red Sox!"

When the weather's nice, the 23-year-old anthropology major can usually be found on the balcony of his Mandarin apartment, watching TV through the sliding glass door. His other passion is reading. Lately, he's dipped into

Magical Thinking by Augusten Burroughs,

Working by Studs Terkel,

Roots by Alex Hailey, and

Nickel and Dimed by Barbara Ehrenreich, along with several histories of World War II.

Ehrenreich threw him into a black mood, however. Her personal account of working minimum-wage jobs in three U.S. cities just seemed too much like the lives of most people -- overworked, underappreciated, underpaid. When he found himself stuck in traffic on 9A, yelling at drivers just before the first game of the World Series, he feared his dark humor might jinx the win. "It was like a Winnie the Pooh cloud was following me all day," he says.

Ebner's fears aren't always rational. He's also terrified of clowns, birds and Martha Stewart. A recent attempt to boil eggs had him in a panic. He had to call four friends to ask when to take them off the stove.

Ebner wishes he could've just called his mother for advice. But the two can't have a conversation these days without arguing. No matter where the conversation starts, it inevitably turns to his clothing (baggy jeans and Polo shirts), his retail job (barely pays the rent on his Mandarin apartment), his hair (buzzed short), his future (with fewer than 20 credits from graduation, Ebner decided to take the semester off from University of North Florida). The discussions are bruising and dispiriting. But Ebner recognizes they're not really about his appearance or career. The issue for both of them is gender.

In the past year, Ebner acknowledged -- first to himself and then to family, friends and employer -- that he is transsexual. Born biologically female, he's begun to live full-time as a man. He's seeking hormone treatments to begin the physical transition and ultimately wants to have sex-reassignment surgery. It will cost from $6,000 to $36,000, depending on what he has done, and it will have to come out of his own pocket.

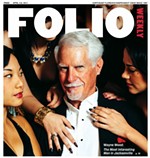

Ebner asked

Folio Weekly to refrain from printing his female birth name because he no longer uses it and, frankly, it makes his skin crawl. (His mother still uses it.) The initials L.J. are a temporary identifier until he legally changes his name. He wants something that sounds Irish and old-fashioned. And something unambiguously male.

Maybe Colin, he says. "That's a good Irish name."

Surgically changing the human body to achieve an idealized self-image -- from Michael Jackson to Greta Van Susteren -- is no longer shocking or even rare. Removing genetic traces of ethnicity by reconfiguring the nose or eyes, or pumping up boobs, lips and backsides, is more socially acceptable than ever. In some cases, it's almost considered obligatory self-improvement.

Sex-reassignment surgery is the most radical form of self-invention. It's also a repudiation of the body at its most basic level. A female making the transition to male must take hormones that will coarsen body hair, lead to beard growth and deepen the voice. The chest broadens. Sex drive increases.

Some transsexuals stop there. Others seek breast removal, hysterectomy and implants to create a functional penis and non-functional testicles. Ebner hopes to begin male hormone treatments soon. With a retail-job income, he'll be forced to put off surgery -- maybe for years. But he wants it.

"If I could have surgery yesterday, I would."

Finding a doctor who'll prescribe hormones has been frustrating. Several local doctors' offices hung up on Ebner after learning he sought male hormones, and why. Others acted as if they had no idea what he was talking about.

It's not easy to seek sex reassignment at the southernmost outpost of the Bible Belt. Ironically, though, Jacksonville was on the cutting edge of sex reassignment surgery for decades. Since the 1960s, it had been one of the few places nationally where sex reassignment surgeries were performed. Transsexuals traveled from across the country to the offices of a Jacksonville plastic surgeon. But that doctor's office is no longer involved in the surgeries. The price of medical malpractice insurance killed the specialty. Contacted by

Folio Weekly, the office declined an interview and asked

Folio Weekly not to mention the name of the doctor. "He paid a very high price in this town," said a person who answered the telephone.

With his short hair, nondescript wardrobe and breasts bound in a latex undershirt, Ebner reads as a male at first glance. To his friends, he comes across as a quirky, somewhat nerdy guy. There's something less determinate about his round, childlike face, smooth skin and Winnie the Pooh references. He's taken pains to coarsen his voice with cigarettes and an exaggerated New Jersey accent, but there is a natural masculinity about him, anyway. His movements are angular and spare, like his personality. He's not macho, but he is male.

Looking back on his childhood, Ebner says, it's clear he has always "identified" as a boy -- even when he had to wear plaid jumpers at the private Lutheran elementary school he attended. He thinks that if his mother could look back honestly, she'd concur. "I lived for P.E. day," he says, when he could trade the hated jumper for gym shorts. Shopping for back-to-school clothes always led to tantrums. His mother would pick out girls' jeans, and he'd refuse to try them on.

"I would only agree to wear them if they were made exactly like boys' jeans," he recalls. "Even then, I wasn't happy."

Ebner recalls, too, when his fourth-grade teacher recorded her students reading "Johnny Tremain." To his chagrin, his voice sounded like a girl's. "That was the first time I consciously heard my voice, and I was like, 'Oh crap.'" He still can't stand to listen to himself on voice-mail.

"In my head, I have a great voice," he says. "Like Barry White."

Despite Ebner's strong, life-long male identification, his mother fervently believes (and hopes) he'll get over "it" if he just focuses on finishing school and establishing a career. Ebner says he can't focus on anything else.

"I've tried to tell her I can't do any of those things until I fix this, but she doesn't get it," he says. Ebner's mother suggested he get psychiatric help and even offered to pay for counseling. She withdrew the offer when he came away from the sessions with a letter authorizing hormone treatment as a first step toward sex-reassignment surgery.

Ebner screens his calls; when he sees his mother's number, he doesn't pick up. He believes family is important, but says he's got enough challenges without trying to cope with his mother's rejection.

"I try not to think about it, because it's not going to change what's going on with me," he says. "And I'm not going to be something I'm not for the sake of a job. I'll eat Ramen noodles instead. I'm done compromising myself for anybody else. I'm done."

When Ebner moved to Jacksonville four years ago to attend UNF, he defined himself as a lesbian -- or as he puts it, a "super dyke." ("I was going to get the cape and everything," he jokes.) His mom didn't like this, either, but Ebner found support at the campus Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender Resource Center, where he met other gender-questioning and trans students. He also read literature about cross-gender experiences, and recognized himself in the stories. Everything finally made sense. He told his girlfriend, Charlotte Rotundo, a tall, shy 22-year-old who met Ebner when they worked together in a pet store, not even a month after they started dating. It might seem like a romance-killer, she admits. "But I was fine with it. I fell in love with a person, not the body."

Rotundo was confused, though. If Ebner was a transsexual, was she still a lesbian? Bisexual? Or did it mean she was somehow straight? Ebner never suffered those agonies. "It's not complicated for him," she says.

Living with his decision has been complicated. Since he began living full-time as male, Ebner has experienced rejection from family, threats from strangers and ridicule from co-workers. Once, when buying a six-pack at an Orange Park convenience store, three men chased him into the parking lot after the clerk who IDed him told them he was a girl, not a guy. He narrowly escaped.

Unlike other trans children who suffer bullying and violence in childhood, however, Ebner felt protected by private school and the supportive environment of the gifted program in his high school. His parents and his peers accepted him as a tomboy, and his avid athleticism fit into his family's values. He and his sister played softball (he was a catcher and a shortstop), and his father coached his team. He went fishing a lot with his dad. (He kept a Tupperware container full of Barbie dolls that friends gave as gifts, but never played with them.)

Ebner never pushed the boundaries, though. He never insisted on being referred to as a boy, never indulged in anything outside the realm of acceptable tomboy behavior.

"You just learn stuff from other people's reactions that 'this is not something we talk about,'" he explains. In middle school, he tripped up and asked another girl, "Don't you wish you were a boy?" Her reaction -- a shocked, emphatic, "No."

Today, his close-knit group of high school friends supports his transition. They say his masculinity is central to who he is. Ebner defines the whole trajectory of his life until now as a coming into himself. "I haven't really changed," he says. "I'm just letting me out."

Talk to many gay and lesbian adults -- artists and others whose gifts or personalities cast them outside the norm -- and they speak of creating a second family. Although rejected by his own, Ebner has found acceptance among a collection of hetero, homo, lesbian and bi youth, first in Daytona, now in Jacksonville. His friends plan nights to get him out of his apartment and away from the books he's always devouring. They worry about Ebner isolating himself. They explain to new friends that he should be addressed with male pronouns.

During the first game of the World Series, a shifting group of eight to 10 friends hung out on the patio of Heather Newberg's pool home near UNF, drinking beer and eating the bounty from a late-night Chick-Fil-A run. Ebner and a straight friend, Samantha, hovered over a laptop singing and dancing to the You-Tube version of his favorite show -- the British comedy,

The Mighty Boosh. To his friends, Ebner's quirky, nerdy, somewhat neurotic personality is charming.

"I think he's adorable," says ex-girlfriend Rotundo, who still talks to Ebner almost daily. "He's like an encyclopedia," exclaims Newberg, 20, a preternatural optimist majoring in elementary education at UNF, who met Ebner at the St. Johns Town Center store where they both work. Newberg sometimes cooks for Ebner to make sure he's eating right. She sympathizes with his single-minded gender quest, and she declares he'll transcend the obstacles she knows he faces from the disapproval of larger world.

"He's so smart, I think he's going to end up doing something really cool," Newberg says. "I see so much potential for him."

Lauren Jennings, 23, has known Ebner since the sixth grade. Both attended the gifted program at their Daytona Beach high school and were members of an informal clique of six friends who called themselves "The Darlings." They would get together once or twice a month to watch movies, swim and talk. The Darlings ranged from a conservative Republican girl known as "So Beige" to Ebner, whom everyone figured was a lesbian even if he didn't know it at the time. Jennings says it surprised everyone in the group when Ebner announced in 12th grade that he was dating one of their male friends. She thinks he was attempting to conform. (Ebner jokes that the guy was much more feminine than he.)

When Ebner came out as gay then, it was no surprise. And two years ago, when he told Jennings he was a transsexual, she understood. "He was just very masculine, even before he began the transition. In the ways he thought, and he's always been absolutely brilliant, it made more sense to look at him as a guy."

Jennings says Ebner is happier since the disclosure. It had always troubled her how his confidence suffered as his friends reached puberty and then their teenage years. Menstruation and the growth of breasts seemed like a betrayal by his body. He always seemed uncomfortable with himself, she says. "I hope, for him, having that knowledge [that he's a transsexual] gives him peace. I'm sure it's easier. It seems like a weight has been lifted off his shoulders."

But Ebner is still very much at war with his body. He cringes if he catches a look at himself in a mirror. He says he would shower in a wetsuit if he could. "When I look at myself in the mirror, it doesn't match at all who I am in my brain. I feel like I'm wearing a big scary costume and it will suffocate me if I don't tear it off. It's like a full-body mask that will give you rubber poisoning."

His turmoil is both about his biology and about the way others perceive him. His desire for hormones and surgery is driven by the need to feel OK with himself, he says, and to fit in. A part of him would be happy, he says, to be a regular working Joe. And he believes he'll feel a comfort with himself after surgery -- and a wholeness that he's never known.

Jennings says seeing her friend so conflicted about his physical self is hard. So is anticipating what's ahead. "I'm scared for him," she says. "But at the same time, I would much rather have him have this life and have this huge challenge of being accepted for who he is than to have an inauthentic life."

Adolescence is fraught with anxiety for many. Physical changes are frightening. Confidence crumbles. And there's no easy way for the adult who counsels such youth to decide if gender uncertainty is part of a larger questioning of sexuality, a struggle with body image or an expansion of the accepted definition of womanhood, says Lynne Carroll, a professor in the mental health counseling program at UNF. Even the image of being born in the wrong body has become a catchall explanation for gender struggles.

"Most folks experience their gender dissonance in different kinds of ways," she says. "For some, it's that immediate sense that begins in childhood. Others may at first question their sexual orientation. You have to appreciate that one size doesn't fit all."

The American Psychiatric Association estimates that one in 10,000 males and one in 30,000 females experience a transsexual disconnect between their biological gender and their self-experience, but there are no hard statistics, says Carroll. There are also no solid figures on the number of people who've had the surgery and transitioned to their gender of choice.

The condition was given a name and a diagnosis -- gender dysphoria -- by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980, although the APA has been discussing removing the category since 1993. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (

wpath.org), based in Minneapolis, has established a standard of care for the treatment of gender identity disorders, which is accepted internationally. The diagnosis begins with strong cross-gender identification and a persistent discomfort with one's biological sex -- to the point that it becomes all-consuming. The transsexual identity should be persistent for at least two years before medical treatment begins and WPATH recommends psychotherapy throughout the process. If hormones and surgery are sought for physical sex reassignment, medical protocol requires that the person live as the gender they're moving toward for a year before the medical procedures begin. Some transsexuals adjust to their identity without hormones or surgery. Others take hormones and choose not to have surgery. Still others live in a gender-malleable way, taking on the external accouterments of one sex or the other at will.

"Some young people today don't want to be forced into a binary identification of one gender or the other," says Carroll. "We are maybe still too attached to what it means to be male or female."

But for all of them, messing with gender roles can be dangerous. Someone who doesn't present themselves as clearly one gender destabilizes the whole notion of gender, says Carroll. Some people react violently. "It's probably one of the first things we notice about someone. We organize our ideas of a person around their gender. I think that's why sexually ambiguous people are often targets of violence or physically or psychologically abused. It's called transphobia."

At JASMYN, Jacksonville area teens and young adults who are questioning their gender identity find safe haven, says executive director Cindy Watkins. It's an important refuge in Northeast Florida's religiously conservative community.

"If your life experience is different, you ask who you are and what does that mean to your family, to your career, to your faith community," says Watkins. "They're trying to understand complex questions. To be able to do that without a lot of pressure or hostility is a very real and unique need."

She says the best advice she can give kids is to have respect. "It's not overly complicated. You have to give basic respect to people who are different than you. You may not understand them. You may have biases about their life experiences, but you can be respectful. We should all be able to be who we are without threat of violence, fear of intimidation, without emotional harm and rejection."

When he was first hired as a retail cashier at St. Johns Town Center, the company (whose name

Folio Weekly is withholding because Ebner says his managers probably won't be comfortable), issued a nametag to him printed with his given name. He dealt with that indignity by forgetting to wear it every time he worked. But when corporate honchos were visiting the store, Ebner's supervisor informed him that everyone had to be in full uniform, and that meant nametags.

"I freaked out a little bit," he says. He refused to wear it; the discussion got kind of heated. "I don't cry a lot, but I got so mad I cried. It's like a sketchy big step saying, 'This is real.'"

Someone (he thinks it was the administrative assistant) suggested "L.J.," and crisis was averted. For Heather Newberg, who works with Ebner, it was the beginning of a thousand questions. After gaining understanding, the Middleburg native now intervenes and explains Ebner to new employees to make sure they use male pronouns in addressing him. "I like to catch someone before they slip up," she says. "And he's told me so much information about it that I'm able to answer their questions."

Newberg has even intervened in conflicts between Ebner and his mother. One day, Newberg had him call his mother and put her on speakerphone. She held up cue cards throughout the conversation, with messages like, "Stay Calm." When his mother said she didn't understand Ebner, Heather held up a note, "Here's your opportunity to explain."

"I don't want to take full credit because I don't know what all their conversations are like, but I think it went really well," she says. "At the end of it, his mother started calming down and just discussing it."

Newberg raised a cue card. "This is great!" it read. "You're really getting through to her."

Folio Weekly tried to contact a number of local transsexuals who've completed surgery and now live as their gender of choice, including one professional. All of them feared the repercussions of an interview. When they began their transition, all were fired from their jobs.

Employment discrimination laws don't protect transsexuals. Ebner recognizes he risks losing his job, too, because of this article, but he's says he's tired of hiding who he is. Most of the time, he adds, his sense of humor deflects people's anxieties.

"I'll make you laugh so you won't beat the shit out of me," he says. But he recognizes that people who find it difficult to read whether he's a woman or a man are deeply disturbed by it. He believes he's been turned down for jobs because, on his application, he still has to identify himself as female. When he shows up for an interview, his potential employers are understandably confused.

"I'm unsettling to some people. I make them uncomfortable. Gender is one of those things that's so cut-and-dried. It's scary for people who have no experience," he says. "In truth, it's scary for me."