Yes, Virginia, There Is an American Dream

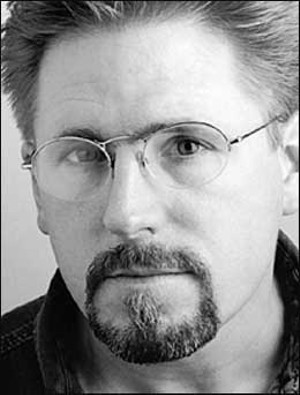

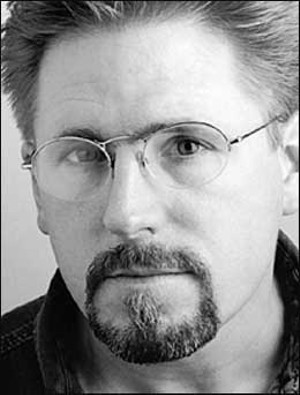

Courtesy C.J. Hribal

C.J. Hribal

C.J. Hribal is the editor of The Boundaries of Twilight, an anthology of Czech and Slovak writing; and the author of the novel American Beauty, the short-fiction collection The Clouds in Memphis and this year’s The Company Car, a sweeping novel about the Czabeck family’s 50-year pursuit of the American dream. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, he is a professor of English at Marquette University and sits on the fiction faculty at the Wilson MFA Program for Writers. In this email interview, Hribal discusses The Company Car, outlines his writing habits and methods, assesses the changes he sees in the national character and the American dream -- and explains his preference for paging, rather than scrolling, through books.

Q: Your most recent novel, The Company Car, is available by digital download in Adobe or Microsoft Reader formats. Why give readers those options?

HRIBAL: I’d like to have it as a book on tape (or CD), but a lot of people prefer this other kind of portability. That was a decision made by Random House. Personally, I’m still a fan of the clunky old book.

Q: Which books have you purchased and read in those formats, and how does the experience compare to paging through a hardcover or paperback edition?

HRIBAL: I haven’t. I’m still wedded to the experience of smelling a book’s pages, flipping through them, marking them with a postcard, tracking my progress through the book by that card or bookmark, etc. I’m sure you can get just as lost in the electronic version -- different strokes for different folks and all that -- it’s just that the physical book is still what I prefer.

Q: You were down in Gurnee on Oct. 8 for an appearance at the public library there. Do you have any purchases to declare from the enormous Gurnee outlet mall?

HRIBAL: No, I tend to avoid those things. I did stop on the way home, though, and bought a lottery ticket -- the first time I did that in a couple of years. It was up to $205 million or something. I don’t play when it’s only $15 or 20 million, but when you get over a $100 million -- hey, that’s real money.

Q: How does being an AFS student in Sri Lanka resonate in your adult life?

HRIBAL: It opened me up to possibility. It made me aware of things going on in the world that were larger than just what I knew about in my little corner of it. I think it was there that I realized how important knowing about the world and its people was, and why I shouldn’t take the luck of my birth for granted. You can laugh and say, “Yeah, yeah, yeah, let’s all hold hands and sing Kumbaya!,” but I really think my attitudes about what it means to be a citizen, and what I want my children to know about their responsibility to this planet and to other people, came from my time there.

Q: You had youthful ambitions to be a writer-photographer for National Geographic. What was the appeal? Are you a subscriber today?

HRIBAL: My first ambition was to be an oceanographer. That morphed into wanting to be a writer-photographer for National Geographic. Both occupations, you’ll notice, would have required a land-locked boy growing up in the Midwest to leave said Midwest. Travel, exotic lands, being paid for my curiosity -- what’s not to like? I started taking journalism courses in college, though, and it seemed that everything that I was most interested in fell outside that who-what-when-where-why inverted pyramid they teach you. I was a lover of tangents. I took a fiction writing course a little later in college and said, Oh, so this is where all that stuff I like belongs. And although I’ve lived in a number of cities around the country, I’m living now back in the Midwest, and have been quite happily for the last 15 years. And yes, I do subscribe to National Geographic. Isn’t that required when you have kids?

Q: You worked in a hotel, a bookstore, canning factories and waste management before finding traction as a published author and academic. What do you imagine doing had you not been published?

HRIBAL: Probably scaring the bejesus out of my mom, possessing a Master’s degree and working as a night manager in a hotel. Seriously? I don’t know what I’d have done. I thought about law school for a little while -- like for maybe a day and a half. And soon after grad school I even applied once to work at a publishing company as an editor. The woman who interviewed me was very kind. She said, Your heart isn’t in this. Why don’t you go back home and write? She saw right through me, bless her. I’m lucky -- I really believe this is what I was put on this planet to do.

Q: Where were you and what were you doing when you conceived The Company Car? In what form did the novel first appear to you?

HRIBAL: I started thinking about this novel back in grad school, and started thinking about it seriously, as in taking notes, about 10 years ago. I knew I wanted to write a big novel about America in the second half of the 20th century and focus on just one family. I knew I wanted it to be funny and forgiving but a little dark. Seven years ago I was blessed with a sabbatical from Marquette for a year, and I thought to myself, it’s now or never. I printed out my notes -- 50 pages, single-spaced -- and I drafted most of the first draft that year. I saw each chapter as having a big scene in it, and the scenes would spiral into each other, sort of like a slinky.

Q: Where in Milwaukee do you live, and why?

HRIBAL: I live in the Cold Spring Park neighborhood, just west of downtown and the Marquette campus. I can bike to work, bike to just about anywhere I want to go, and it feels like a real neighborhood. People watch out for each other. I used to joke that in my neighborhood there’s a three-porch rule -- when you walk the dog you have to stop at at least three porches and chat. My kids when they were younger played kickball in the streets with a plethora of kids of all ages, they have friends for whom the color of their skin matters not a whit, and we’re close to all the things they and I like to do -- soccer, biking, the library, the lakefront, etc. Plus I could afford a house here that’s roomy and comfortable and has character.

Q: Are there still families in your neighborhood who are comparable to the Czabeks?

HRIBAL: Not so much anymore in the sense of second and third generation descendants of Central European immigrants who fought in WWII and/or Korea and had big families and who later moved out to the suburbs and then the exurbs. That particular train has already left the station. There’s an old couple kitty-corner from me who fits that profile, only they stayed in the city and their kids moved out. But in the sense that there are families here who, regardless of ethnic background, are all chasing the American dream: get a home, get the kids grown safely, strive to improve your lot, feel your dreams pinched a little by circumstance -- sure, that’s still happening.

Q: To what extent do Wally and Susan Czabek embody your parents?

HRIBAL: Wally and Susan are everybody’s parents. At readings I get people telling me, “That’s my dad!” or “My mom was just like that!” I got an e-mail recently from a man who said, “You’ve written my story. I am Wally Czabek.” Fortunately, he didn’t mean that literally. And I have to say that identification thrills me, because what I wanted to do through Wally and Susan was capture that sense of excitement, and dreaming, and disappointment, and more dreaming, and all that striving and sacrifice that a whole generation of people went through, my parents included.

Q: Why do some people yearn for those Eisenhower-era notions of normality and the American Dream that you revisit in The Company Car? Was there ever such a thing as normal? Has the American Dream become an anachronism?

HRIBAL: Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. And yes, there’s still an American Dream. It’s been dented and beaten about the ears some, but as a people we’re still game and grinning. It’s probably one of our most endearing qualities -- the ability and desire to dream. Gatsby had it, Cubs fans still have it, Wally and Susan have it. And I have to say about The Company Car that it also peels back that notion of “normal” a little -- underneath all that optimism were some pretty anxious people, desperate to be normal, to fit in, to find the safe place where everything would be okay. And I don’t really believe there is such a place, which is not to say that the effort to find it isn’t noble and endearing.

Q: The Company Car is as much about the landscape as it is about the people who populate that landscape. How attentive are you to regional planning issues, and what reactions do you have to the changes you see?

HRIBAL: I haven’t studied it as a planner, but I’ve thought about it as an interested citizen. I’m no fan of sprawl, nor of the tax subsidies that go into highway construction that encourages sprawl. (It’s particularly irksome when people say “the highways are free,” but mass transit shouldn’t be funded. What they’re really saying is, “I want the government to pay for my perks, but I don’t want money to be spent on other options.”) The issue of farmland being converted into subdivisions is a tricky matter. It adds to the tax rolls--good. It changes the character of a place -- not so good. Farmers can fund their retirement -- good. Farmers get squeezed by taxes and are forced to sell when they don’t want to -- bad. What happens when so many people move to the country to enjoy rural living that it’s no longer rural? That actually figures into my next novel, so I’ll leave it at that. It’s something I’m continuing to explore.

Q: What has been lost across the 50 years you follow the Czabeks? Have we gained anything?

HRIBAL: The biggest loss, I think, has been a change in the national character. It used to be, “We’re all in this together.” Now it feels more like, “I got mine, screw everybody else.” A case in point: people used to vote in favor of school bond issues as a matter of course. They saw it as good for everybody. Education was important for its own sake. Teachers were important. Now, to too many people, they’re cast as the enemy. The results of that rather pernicious campaign, which is based on devaluing the teacher so you can justify not funding education, is that the pool of good people who want to teach our young people is shrinking. It’s no longer a job people respect, and people know there’s no money in it, so why do a noble thing like teach? People say, in talking about school funding, “Well, you can’t solve a problem by shoveling money at it.” No, but shoveling money at something is the way you make clear your priorities. We’re shoveling money at Iraq -- that was this administration’s priority (among others). There’s a website that gives you what the money spent in Iraq could have been used for -- had we embraced other priorities. It’s scary, and very sad, how misspent those billions and billions were.

In terms of what we’ve gained -- goodness, better health care, all kinds of technology, a better awareness of civil rights, an evolving awareness of women’s rights, women’s choices -- there’s tons of things that are better.

Q: Where, when and how do you prefer to write?

HRIBAL: I write in the mornings and early afternoons when I can get them, usually in the upstairs office in my house, sometimes at the dining room table or on the porch or in my side yard when I want a change of pace. Every once in a while I’ll go to a coffeeshop --the white noise of coffeeshops is almost like silence for me. I like that. I often draft or take notes in longhand in notebooks, and, as of The Company Car, because I knew the manuscript was going to be big, write the first full draft on my laptop. I need something to sip -- coffee, tea, water -- handy, and no distractions.

Q: What are you writing now?

HRIBAL: I’m working on a new novel now, set in Augsbury, and it’s about a guy who inherits the family farm from his widowed mom, who’s remarrying, and to save the farm he wants to turn it into a tourist farm (with llamas and hay rides and miniature golf and things like that), and he’s bungling it big-time.

Q: What was the last book you read that you would recommend, and why would you recommend it?

HRIBAL: Probably Lan Samantha Chang’s Inheritance, which I just re-read. It’s a beautifully spare but rich novel that spans several generations of a family in pre-war China and follows them through to the present day. The prose is just luminous. The other book would be Peter Turchi’s Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer. He’s incredibly smart about the creative process (and not just the writing process), and it’s got terrific illustrations.

Q: Do you have any tattoos?

HRIBAL: Nope. My body is a temple. The temple may be in ruins, but there’s no graffiti on it.