Many called him the future president of the United States. When he died, a squadron of airplanes dropped flowers over those attending the funeral services at Claremore airport and people scattered to gather the fallen blossoms. In Washington, D.C., Congress adjourned while the grief-stricken family received a well-publicized letter from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. California’s governor ordered a day of mourning as flags flew at half-staff in Los Angeles County. An estimated 100,000 reportedly paid their respects at Forest Lawn cemetery. Church bells tolled in 100 cities nationwide in remembrance. For two silent minutes, more than 12,000 theaters darkened across the country and all Hollywood studios stopped production.

A myriad of diverse groups observed his passing. Cherokee Indians in California planned to invoke ancient funeral rites performed only during a chieftain’s passing. A Catholic priest and Protestant minister presided over a Hollywood Bowl memorial service broadcast that included a Hebrew mourning chant sung by a Yiddish performer in an outpouring described by author Lary May in “The Big Tomorrow.” In other parts of town, a black fraternal group, “The Friends of Ethiopia,” joined a parade honoring the fallen icon while a wreath that read “Nosotros Lamentamos la Muerte de Will Rogers” was placed on Olvera Street.

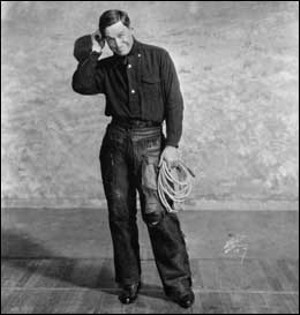

At the time of his death, Will Rogers literally was on top of the world. According to a biography by Joseph H. Carter, the native Oklahoman starred in more than 70 films of the Twenties and Thirties, and wrote more than 4,000 syndicated newspaper columns — published in The New York Times — and six books. Also a popular radio commentator, he befriended powerful politicians and traversed the globe.

An ill-fated flight with aviation pioneer Wiley Post ended Rogers’ life at age 55 on Aug. 15, 1935. The hybrid Lockheed airplane, fashioned from a damaged Orion’s fuselage with the wings of a Sirius, carried added pontoons designed for water landings, Time magazine reported. Taking off for Point Barrow, Alaska, the ship sputtered at 50 feet, veered right and plummeted out of control. In the Arctic night, a whaleboat crew puttered across streams and spotted the wreckage near Walkpi, an Eskimo village. Though Rogers’ lifeless body lay beneath a sleeping bag, his Ingersoll watch was still ticking.

Rogers’ legacy lives on. Oklahomans have seen the black and white photographs and read his name honored on schools, airports, naval ships and monuments. We know the populist humorist never met a man he didn’t like, but did that include cowboys? American Indians? Or pro-gun-control communist peaceniks in favor of the redistribution of wealth? Seventy years after his death, scholars are still debating the political beliefs of Will Rogers.

“I would say that Rogers is a Rorschach test into which people bring many points of view and they often end up finding them,” said Peter C. Rollins, Regents professor of English and American/film studies at Oklahoma State University. “And that’s the virtue of him. That’s why he’s worth reprinting. That’s why he’s worth restudying.

“Every generation will have a different Will Rogers. And so the debate is not something that’s going to end with an answer or a conclusion. It’s a debate that will be ongoing. And there will be new voices and new perspectives.”

“I don’t belong to any organized political faith, I am a Democrat.”

—Will Rogers, 1930

Have conservatives in Oklahoma marginalized Will Rogers’ legacy by perpetuating a homogenized, stripped-down version for the masses? That’s what Kurt Hochenauer thinks.

Hochenauer, an English professor at the University of Central Oklahoma, doesn’t pretend to be a Rogers scholar, but that hasn’t stopped the modern British literature instructor from commenting about Oklahoma’s most famous — and most popular — native son. The UCO professor recently wrote “Will Rogers, The Radical” as part of his “Okie Rebels With a Cause” blog at

www.okiefunk.com.

While right-wing Oklahomans criticize Woody Guthrie’s moral legacy, Hochenauer said conservatives are trying to manipulate the message of Rogers, conveying an apolitical version of the fellow Okie populist through reductionism.

Hochenauer calls this distortion of Rogers “a mere caricature, a cartoon cowboy with a twirling rope and a penchant for somewhat silly and untrue aphorisms. …” Hochenauer claims Rogers’ writings reveal a pacifist believing in the redistribution of wealth, a proponent of gun control and man open-minded toward socialism and Russia’s early communist experiment.

While Rogers certainly wasn’t a dope-smoking hippie, he was no warmonger. Regarding Rogers’ thoughts on war, the columnist addressed the issue in the Tulsa Daily World June 28, 1925:

“Somebody is always telling us in the papers how to prevent war. There is only one way in the World to prevent war and that is FOR EVERY NATION TO TEND TO ITS OWN BUSINESS,” wrote Rogers, who was known to pepper columns with creative capitalization and spelling. “Trace any war that ever was and you will find some Nation was trying to tell some other Nation how to run their Business. … All these Nations are interfering with some other Nation’s personal affairs, BUT with an eye to business. Why … don’t we let the rest of the world act like it wants to.”

Or consider this from his New York Times column published Dec. 5, 1931:

“I am a peace man,” Rogers wrote. “I haven’t got any use for wars and there is no more humor in ’em than there is reason for ’em.”

Another New York Times column printed Feb. 10, 1932, expressed isolationist overtones.

“If we could just let other people alone and let them do their own fighting,” Rogers wrote. “When you get into trouble 5,000 miles away from home, you’ve got to have been looking for it.”

Hochenauer said Rogers’ writings harshly criticized governmental policies and promoted the redistribution of wealth concept. In 1928, Rogers wrote “All these big moneyed people, they are just like the underworld …” in the Saturday Evening Post. As banks failed and the stock market crashed, Hochenauer said Rogers became politically activated by the Depression, shifting to the populist left.

“Sure must be a great consolation to the poor people who lost their stock in the late crash to know that it has fallen in the hands of Mr. (John D.) Rockefeller, who will take care of it and see it has a good home and never be allowed to wander around unprotected again,” Rogers wrote Nov. 1, 1929, in The New York Times. “There is one rule that works in every calamity. Be it pestilence, war, or famine, the rich get richer and poor get poorer.”

Rogers’ “Bacon and Beans and Limousines” speech also addressed the poverty issue on Oct. 18, 1931:

“(T)here’s not a one of us has anything that these people that are without it now haven’t contributed to what we’ve got,” Rogers said. “I don’t suppose there is the most unemployed or the hungriest man in America has contributed in some way to the wealth of every millionaire in America.”

Hochenauer also argues Rogers was an advocate of strict gun control, citing this Sept. 20, 1925, comment published in the Tulsa Daily World:

“(T)he automatic pistol … it’s all right to have it invented, but it should have never been allowed outside the army, and then only in war times,” Rogers wrote.

“Every day brings new schemes in the papers for relief. The Russians have got a five-year plan. Maybe it’s terrible but they got one. We been two years just trying to get a plan. . . . We will just have to save ourselves accidentally. That’s the way we stumbled on prosperity.”

—Will Rogers, Aug. 20, 1931

Perhaps the most controversial claim made by Hochenauer is Rogers’ stance on communism. The humorist is quoted as writing “If Russia succeeds it will be because they got no stock market” on Oct. 25, 1931. Hochenauer said Rogers was sympathetic to the communist experiment before World War II and prior to America’s knowledge of the Stalin atrocities.

“That’s what (conservatives) do essentially with Woody Guthrie,” Hochenauer said. “They say, ‘Look, he was a communist.’ Of course, you wouldn’t say that about Will Rogers, but you could certainly say he was sympathetic to communism.

“They tend to just forget that part of it. There are many reasons for that, a lot of it has to do with (the fact) that Will Rogers was this mainstream actor and movie star and he was a historic figure that the state had to deal with in some way because he was so famous.”

Referencing a column published Aug. 16, 1931, Hochenauer said Rogers acknowledged that Americans should pay heed to Russia’s five-year plan with hopes of boosting the economy.

“Ten men in our Country could buy the World, and ten million can’t buy enough to eat,” Rogers wrote. “So the salvation of all that might come out of these Cuckoo Russians. If it does, it will have paid for itself whether the whole five year plan works or not. So we ain’t going to get nowhere cussing ’em. We better watch ’em, and if they got anything any good, why cop onto it, and maby we can feed everybody.”

Hochenauer notes another column written by Rogers later that year on Sept. 6, 1931:

“So they can have all the theories and plans they want but till you get rid of something and put people back to work, you ain’t going to be able to fix it,” Rogers wrote. “You can call it co-lition, Republican, Democrat or Bolsheviki. But folks got to have work.”

Not everyone is convinced of Rogers’ communist stance. “The Big Tomorrow” author May, an American studies professor at the University of Minnesota, said Rogers wrote sympathetically of the Bolshevik revolution but realized religion and private property were being undermined by the state’s efforts “to create new collective farms.”

“You can find as many quotes, if you wanted to be selective about Will Rogers, which were favorable to the Soviets,” May told Oklahoma Gazette. “…And then you could find the flip side … in which he flies through Russia and criticizes the confiscation of wealth from the small farmers; he hates it, and he hates the assault on religion. So if you’re anti-communist in the postwar period or even at the time, you could select out those quotes and say, ‘Look at how bad he is.’ Rogers does not like centralized power in the state.”

“Everybody is ignorant. Only on different subjects.”

—Will Rogers

What does Hochenauer say to critics labeling him as another liberal professor wanting to rewrite history? Is the UCO professor trying to manipulate Rogers’ legacy for political leverage?

“I have nothing really to gain for arguing this except my political beliefs,” Hochenauer said. “I’m not making an academic career out of Will Rogers.

“There’s some truth to the fact that I’m trying to claim this segment of Will Rogers for liberal and progressive political beliefs, and I don’t really apologize for that. That’s what interests me about Will Rogers — his politics. … I’m trying to claim him for the liberal and progressive cause, and I think I’m right.”

Or left. Hochenauer’s blogging on Rogers drew the ire of UCO colleague Reba Neighbors Collins, the director of the Will Rogers Memorial from 1975-1989. Collins, who received her doctorate from Oklahoma State University on “Will Rogers, Writer and Journalist,” wrote Hochenauer an e-mail, which he posted on his site.

“All I ask is that you spend some time studying Will Rogers’ own writings,” Collins wrote to Hochenauer. “He will stand the test of time if you read him ‘whole.’”

Collins, a professor emeritus at UCO, said Hochenauer simply doesn’t understand Rogers. Hochenauer claims Rogers was at least “a leftist moderate” who was quite aware of diversity and equal rights for different ethnic groups. And he thinks the fascinating debate on Rogers’ politics keeps his legacy alive.

“If (Hochenauer is) going to teach, I wish he’d get to know Will Rogers and then teach him like he is,” Collins told the Gazette. “You can have any opinion about anybody, but if you have a knowledgeable opinion then let him teach because I think they should.”

And, for God’s sake, don’t call Rogers a liberal.

“To me, there’s a right and a left and liberal is on the left,” Collins said. “(Rogers) was not left of center. He was more in the center. And it wasn’t whichever way the wind blew.

“Back then, Will Rogers at one time said he was liberal about something. Liberal meant generous at that time, and he was extremely generous. And that was exactly what he meant — it meant being open-minded. It didn’t mean what it means today.”

Collins said Rogers toured the country during the Depression to raise money for the hungry. He had pestered President Herbert Hoover to give money to feed the poor. Collins paraphrased Rogers as saying, you can’t let the hungry starve, but you shouldn’t give people money for doing nothing because they wouldn’t want to work again.

In the end, Collins said Rogers was just an “equal opportunity offender.”

“You can’t call that liberal, you can’t call that conservative,” Collins said. “It’s Will Rogers. He really worried about it at times — this was particularly true during the Depression.

“He didn’t blame Hoover for the Depression because it was a long time coming.”

And professors labeling Rogers as a leftist, liberal communist sympathizer are taking the humorist too seriously, Collins said.

“If you studied it with any kind of sense at all, you’d really have to be looking at it through weird glasses,” she said.

“… He does think people have a right to their own thoughts, that if somebody wants to be a communist or whatever, it’s all right with him.”

“Will’s traits — visible in his writings as vividly today as when he set them to paper — are the unending virtues of the American Indian. Will Rogers introduced the world to this ethical view of life.”

—W.W. Keeler, principal chief, Cherokee Nation, 1973

Lest we forget, Will Rogers was 9/32nds Cherokee, slightly more than one-quarter blood. In “The Big Tomorrow,” May notes that Rogers was born to Clem and Mary Rogers in Indian Territory. His parents were members of a class called “mestizos,” people of mixed indigenous and European ancestry. Inheriting the ethos of the Cherokee trickster, Will Rogers fused humor with political drama to identify with a multicultural democracy where a sense of community and freedom merged.

Rogers’ departure to foreign lands in the wake of the Dawes Act is perceived by some biographers as a revolt against his Cherokee past, but May said the young man was looking for a new frontier for Cherokee relocation. Once Rogers realized that exploited laborers and monopolized landholdings made Latin America undesirable, he adjusted “to a hyphenated or dual citizenship,” May said.

“I was always proud in America to own that I am a Cherokee, but I find on leaving that I am equally proud that I am an American,” Rogers wrote.

A bedroom in Rogers’ western-style ranch house displayed a picture of Chief Sequoyah, May said. Rogers drew on his Cherokee heritage to spread a “more inclusive and radical vision of nationality.”

“(Rogers) was traveling around … in South America and South Africa,” Collins said. “… He wrote a letter to his dad one day. His dad was very active in Cherokee politics. … He wrote a letter and said, ‘For the first time, I’m glad to be called an American. And the reason is that everything over here that’s good, they call it American.’”

As a comic headliner with the Ziegfeld Follies, Rogers could say he was more “American” than the Anglo-Saxons. May said his fame spread to local radio and eventually to columns in The New York Times.

“The great irony is that he was (an) Indian who was accepted by the audience because he was dressed up as a cowboy and did cowboy stuff,” said William W. Savage Jr., a history professor at the University of Oklahoma specializing in the American West. “I think that’s the basis for his initial acceptance.

“You get to the point where you can’t play a cowboy and do the kind of humor that he wanted to do. But I think that was the basis for his acceptance in the beginning of his popularity with Ziegfeld, and certainly that’s how he started his career.”

During the Depression, Hollywood executives discovered that technologically advanced talking films starring Rogers meant box office gold, May said, as filmmakers provided a narrative structure to the star’s well-known views. He cited a “Will Rogers formula” in film appearances acknowledging an equal status for women, which was a Cherokee tradition.

“As Rogers gained success, his Hollywood films and radio shows

promoted a major realignment of cultural authority from the top to the bottom of society,” May wrote. “The mass arts now provided what was missing in the past: a free space that promoted images and voices of cultural communication and radical reform.” In contrast, the cinematic offerings of his contemporary, John Wayne, “evoked the image of the pure Anglo-Saxon hero … who protected established institutions and used violence to conquer enemies.”

May said Rogers, an early Screen Actors Guild member, even took a jab at settlers on the frontier:

“We’re always talking about pioneers and what good folks the pioneers were,” Rogers said. “Well, I think if we just stopped and looked history in the face, the pioneer wasn’t a thing in the world but a guy that wanted something for nothing. He was a guy that wanted to live off everything that nature had done. He wanted to cut down a tree that didn’t cost anything, but he never did plant one, you know. He wanted to plow the land that should have been left to graze. He thought he was living off nature, but he was really living off future generations.”

Rogers, who said he hoped his Cherokee blood didn’t make him prejudiced, said the extreme generosity of the Indians made it possible for the Pilgrims to land in America.

“Suppose we reverse the case,” Rogers said. “Do you reckon the Pilgrims would have ever let the Indians land? Yeah, what a chance, what a chance. The Pilgrims wouldn’t even allow the Indians to live after the Indians went to the trouble of letting them land, of course, but they’d always pray.

“… I bet any one of you have never seen a picture of one of the old Pilgrims praying when he didn’t have a gun right by the side of him. That was to see that he got what he was praying for.”

“I used to wonder why it was that Will Rogers was the head man of all the public figures of his day. … Then one day, I realized what it was. If you took Will Rogers and pitched a dab of whiskers under his chin, put a red, white and blue hat on his head, crammed his legs into star spangled pants, he’d be Uncle Sam.”

—Clarence Kellend, novelist, 1935

In the Thirties, radio commentators often called Rogers the “Number One New Dealer.” Three years after Rogers’ fatal Alaskan plane crash, President Roosevelt presided over the dedication of the Will Rogers Memorial.

“There was something infectious about Will Rogers’ humor,” Roosevelt said. “His appeal went straight to the heart of the nation. And above all things in a time grown too solemn and somber, he brought his countrymen back to a sense of proportion.

“With it all, his humor and his comments were always kind. His was no biting sarcasm that hurt the highest or the lowest of his fellow citizens. When he wanted people to laugh out loud, he used the methods of pure fun. And when he wanted to make a point for the good of all mankind, he used the kind of gentle irony that left no scars behind it. That was an accomplishment well worthy of consideration by all of us.”

Seventy years after Rogers’ death, the University of Oklahoma Press is printing “The Papers of Will Rogers: Volume Four,” edited by Steven K. Gragert and M. Jane Johansson, which documents the humorist’s rise to national prominence.

Rollins, Regents professor of English and American/film studies at OSU, said Rogers’ enormous body of work remains open to interpretation.

“I don’t think that anyone will ever come up with the real Will Rogers or the one Will Rogers,” Rollins said. “There are just many of them. And, of course, his writings and his life — just like our lives — were immersed in a time frame — the Depression, the boom of the Twenties.”

Rogers profoundly influenced another Oklahoma icon of his era. Woody Guthrie idolized Rogers, “a pure Plains populist,” and even borrowed the format of his folksy “Woody Sez” newspaper columns from the popular writer’s “Will Rogers Says,” said Ed Cray, University of Southern California journalism professor and author of the Guthrie biography “Ramblin’ Man.”

Guy Logsdon, a Tulsa folklorist considered the foremost Guthrie scholar, claimed Woody once said: “My two favorite people were Jesus and Will Rogers.” In the mid-Thirties, Guthrie honed his country philosopher shtick modeled largely after the droll humor of Rogers, said Woody’s friend Matt Jennings in “Ramblin’ Man.”

Unlike Rogers, Guthrie never made more than $50,000 in his entire working life, according to promoter and manager Harold Leventhal in “Ramblin’ Man.” Reared in the middle class, the Okemah folksinger chose a more nomadic lifestyle to rub elbows in farm labor camps, union hiring halls and Skid Row bars.

“Oklahomans tend to admire celebrities or native sons who had made money,” Savage said. “Guthrie never had two dimes to rub together, but you take somebody like Will Rogers who had a helluva lot less social conscience than Guthrie did, and the tendency is to besmirch him (Guthrie) … anything to tar him and make him unworthy of an appearance on the cover of the phone book whereas Will Rogers is liable to pop up on the phone book anytime SBC feels like it.”

May, author of “The Big Tomorrow,” claims a “large scale whitewashing … distorting Rogers’ memory” occurred posthumously, robbing later generations of justification for his rise to become “the most noted public man of his day.” May claimed the Shrine of the Sun, a monument dedicated by a wealthy industrialist in Colorado Springs, Colo., seized Rogers’ legacy to honor what the humorist often satirized: “a business system that colonized and exploited nonwhite people and workers to advance ‘Manifest Destiny’ of the Anglo-Saxon West.”

And how would scholars view Rogers’ politics if he had lived into the Fifties?

“A more telling explanation might have allowed that the call for unity in World War II and postwar anticommunism made Rogers’ ideas seem ‘un-American,’” May wrote.

“The thing that has distorted Rogers’ political philosophy is the Cold War,” May said. “The Cold War came along and said that equal opportunity, democratic rights and freedom from the state (were) automatically opposed to the quality and democracy in opposition to maldistribution of wealth.”

Rogers’ name could have possibly been mentioned in the era’s congressional hearings, Savage said.

Today, Rogers serves as a reflection of his own time and as a reminder of basic human values, Rollins said.

“Every generation will have his own tweak or spin on Will Rogers, and that’s why he’s such a valuable cultural icon,” Rollins said. “All of these descriptions of Will Rogers are wonderful and interesting, and not one of them is necessarily wrong.

“Depending on what you’re looking for, there’s a lot to support almost any argument … but, basically, (he was) an American.”