“I stand before you today as a candidate for the Democratic nomination for the Presidency of the United States. I am not the candidate of black America, although I am black and proud. I am not the candidate of the women's movement of this country, although I am a woman, and I am equally proud of that. I am not the candidate of any political bosses or special interests. I am the candidate of the people."

By the time Shirley Chisholm died on New Year’s Day, at the age of 80, her name had long since dropped off our nation’s collective radar. Her passing went largely unnoticed; not even reported in the media until two days later. For those old enough to remember her historic bid for the presidency in 1972, it doesn’t seem right for a spirited fighter to slip away so quietly.

Chisholm declared her presidential candidacy on Jan. 25, 1972, with eloquent, idealistic sentiment. Her independent style and brash, progressive mindset seemed well suited for a fight in that year’s Democratic primaries. As she once said of her outspoken campaign style: “My greatest political asset, which professional politicians fear, is my mouth, out of which come all kinds of things one shouldn’t always discuss for reasons of political expediency.”

The first black female to win election to Congress in 1968, Chisholm had served in the United States House of Representatives for two terms. Her presidential campaign promised to be an energetic, empowering movement. Nevertheless, Shirley Chisholm knew that to many voters, she would remain just what she claimed she was not: either the black candidate or the women’s candidate.

Traditional party leaders saw her campaign as a hostage of various minorities and would refuse to consider her ideas. Constantly forced on the defensive to justify her mere presence in the race, Chisholm issued combative, abrasive replies that frequently garnered more ink in the papers than the issues she espoused. Why would she want to run such an intimidating gauntlet as the first black woman seeking a major political party’s nomination for the presidency?

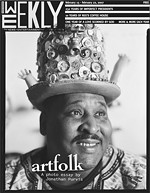

Thankfully for those who have forgotten, or never knew about the significance of Chisholm’s political career, a first-time filmmaker’s recent documentary provides a final chance to understand the lady with beatnik glasses, bird’s nest hair and a defiant personality. Shola Lynch’s film,

Chisholm ’72: Unbought & Unbossed, captures both the feisty ’72 campaigner and the more recent, reflective storyteller. Though the documentary had already been scheduled to air on PBS when news broke that Chisholm had died, its Feb. 7 showing has now gained greater relevance.

Tracking the trailblazer

Shirley Chisholm was born in 1924, in a predominantly black neighborhood in the segregated borough of Brooklyn, New York. Her father was from British Guiana (now Guyana) and her mother was from Barbados. Chisholm’s parents sent her to live with her maternal grandmother in Barbados until she was 10, believing she would receive a better education in a less hostile environment. Upon returning to the U.S., Chisholm attended Brooklyn College where she encountered racism at almost every turn. After graduation, the intelligent and driven woman was rejected by a number of prominent companies before accepting a job at the Mt. Calvary Childcare Center in Harlem. From there, Chisholm went on to teach school, organize community action groups, enter the New York State Assembly and finally, in 1968, become the first black female United States representative.

Half a century after Chisholm’s birth, another black female named Shola Lynch grew up in New York City’s diverse Manhattan environment — a borough and a world away from Chisholm’s home. Lynch’s father taught history at Columbia University; her mother was an activist who earned several professional degrees. A number one-ranked runner in the 800- and 1500-meter races coming out of high school, Lynch chose to run track at the University of Texas. After studying art and history in college, Lynch entered graduate school and continued running, making it to the Olympic trials in 1992 (a damaged disc in her back ended her career just before the 1996 trials). By the fall of 1996, Lynch managed to find her way into the movie world as a production assistant for veteran documentary filmmaker Ken Burns.

“Growing up in Manhattan, race and gender were not issues in my world until I went to college,” Lynch explains. “I knew about the Civil Rights Movement and appreciated what it had done for my generation, but I did so without delving into that generation’s sacrifices. I just thought ‘I’m glad I didn’t have to do that.’”

As a beneficiary of Chisholm’s trailblazing, Lynch never thought of the impact Chisholm’s life and campaign had on her own opportunities. As a youngster, Lynch knew of Shirley Chisholm. She knew that Chisholm had run as the first black female candidate for president, but she had dismissed the story without considering its impact.

“I thought, ‘Well, she had no chance of winning. Why would she do that?’” Lynch remembers. “As I got older and began to understand what it meant, I realized you can win the war without winning the battle.”

One day in 1998, Lynch sat listening to the radio and heard that it was Shirley Chisholm’s birthday. After two years assisting Burns on the award-winning, multi-part documentary Jazz, Lynch had begun contemplating what she might use for a subject in her own debut documentary.

“I didn’t even know she was still alive, but all of a sudden, I thought, ‘Wow, Shirley Chisholm is still alive. This could be it.’”

Winning over Shirley

Lynch had no filmmaking experience when she talked her way onto Burns’ crew as a researcher in 1996, but her background in art and history immediately proved an asset. She worked with Burns for almost five years over the course of two documentaries, serving as an associate producer for both Frank Lloyd Wright and Jazz. Participating from start to finish in such expansive productions gave Lynch an excellent foundation in filmmaking, but working on her own still represented new ground for Lynch.

“It was like being a trapeze artist without a net,” Lynch says. “You can’t look down because you’ll either fall, or worse, you’ll be paralyzed by fear. I knew the way I wanted to share her story. I knew I could make a film. I just didn’t know if I was a filmmaker.”

Delighted to discover that no documentary had yet been produced on Chisholm, Lynch decided she had her subject. Convincing her subject to appear in the film, however, was another, more laborious matter. Living in Florida and far removed from her contentious political career, Chisholm did not necessarily relish a film trotting her out into the spotlight again. Lynch’s initial letter went unanswered and several phone calls were rebuffed before Lynch got her on the telephone.

“I can’t remember what I said, but I filibustered her for a good 15-20 minutes,” Lynch says. “I do remember appealing to her as a teacher, saying this film would not be so much about her as it would be about her cause for future generations to learn about.”

The tactic worked and the film’s first interview commenced less than a week later, with Lynch and her team recording a sit-down with the political pioneer. Chisholm ’72 was a go.

Making history a movie

Comprised of 15 interviews interwoven with news clips and old campaign footage, the film takes its title from Chisholm’s campaign slogan in her historic congressional win in 1968: “Fighting Shirley Chisholm: Unbought and Unbossed.” The movie opens with Chisholm’s announcement that she is entering the race and the cameras then follow her to Florida, where Chisholm competed in her first primary that year. It is soon evident that, despite her earnest entreaties, Chisholm would become a two-dimensional candidate — but not, as expected, as a choice for blacks and women. Chisholm would either be ignored or castigated by most black male leaders for entering the race without their blessing. Instead, women and youth became her most steadfast supporters.

The only predominately male organization that fully endorsed Chisholm’s campaign was the Black Panthers. Many Chisholm supporters and members of the media wanted the candidate to disavow the militant group’s endorsement. In one of the more memorable speeches included in the film, Chisholm refuses, saying the fact that the group chose to work through the democratic process to change the system from within marked a positive sign and should be encouraged. Chisholm then adds a bit of her signature flair to the argument: “If you can’t support me, or you can’t endorse me, get out of my way! You do your thing and let me do mine.”

Interviews with former Black Panther leader Bobby Seale, former National Organization for Women director Arlie Scott, California congressman Ronald Dellums, journalist Jules Witcover and many Chisholm ’72 volunteers paint a wider portrait of the campaign. In particular, those film conversations with her former campaign workers reveal how popular Chisholm was among women voters and among 1972’s newly eligible 18-21 youth bracket, groups attracted to her unbridled progressive agenda.

Despite her supporters' efforts, the Brooklyn congresswoman’s showing in the primaries was unimpressive. In a crowded field of a dozen candidates, Chisholm was forced to pick her battles. Getting out her message proved difficult when the majority of questions posed to her in interviews forced her to defend her right to run. She was constantly accused of doing nothing but siphoning votes away from other candidates. One of the most painful moments captured in Lynch’s documentary comes shortly after Chisholm has successfully filed suit with the Federal Communications Commission to gain entrance to a televised debate between Hubert Humphrey and George McGovern in California. Her victory looks short-lived only a few minutes into the debate, as Chisholm is forced to endure a condescending line of questioning even more distasteful than most interrogations reserved for “spoiler” third-party candidates.

At only 75 minutes, Chisholm ‘72 glosses over a fair amount of history or omits it altogether. Focused on the transcendence of her campaign for the inclusion of minorities, the film hardly touches on many of the key issues championed by Chisholm, including her anti-war stance and her nuanced positions on topics like busing and abortion.

But perhaps these omissions are appropriate. By the end of the film, the viewer realizes that Chisholm’s stances on issues were secondary to her mere presence on the biggest political stage in the nation in 1972. How then, should Chisholm’s success from the campaign be measured, if not by votes? She articulated her larger purpose in her 1973 autobiography The Good Fight:

“The next time a woman runs, or a black, a Jew or anyone from a group that the country is 'not ready' to elect to its highest office, I believe he or she will be taken seriously from the start," Chisholm wrote. "The door is not open yet, but it is ajar.”

The door to credibility remained closed to Carol Moseley Braun in her bid for the presidency in 2004. And only two persons of color have entered the United States Senate chamber since Reconstruction. But perhaps Chisholm’s seed is slowly bearing fruit. Illinois’ Barack Obama recently ended the Senate shutout, and hundreds of women inspired by Chisholm now impact public policy on every level. Barbara Lee was a welfare mom with two children in 1972 when she joined the Chisholm campaign as a volunteer. Today, Lee represents California in the United States Congress.

“‘The audacity of hope’ is what Barack Obama called it [last summer] in his speech [at the Democratic National Convention],” Lynch says. “It made me think of Shirley Chisholm. She made a whole generation think, ‘Maybe I can do this.’ We keep ourselves from greatness far too often. It’s easy to hold yourself back and not risk anything. She didn’t hold back.”

The toughest critic

Lynch and her crew finished the film in January of 2004. Since then, the Sundance Film Festival designated Unbought and Unbossed as an “Official Selection of the Festival,” and the national Rock the Vote and White House Project voting drives utilized the movie to register young voters for last November’s national election. The PBS documentary series POV decided last summer to air the film this February as part of the network’s Black History Month programming.

In March of ‘04, however, Lynch remained uncertain about an audience of one that had yet to view the film. During the entire production process, Lynch says Chisholm was so trusting of the project that, beyond her onscreen interview, she stayed clear of the crew to allow them to film and edit without meddling from the subject herself.

“I was really nervous as to what her reaction would be when she finally saw the whole finished product,” Lynch admits. “It took until March to finally get her to watch it. I had to bring a VCR with me down to her house in Florida because she didn’t have one.”

Sitting in Shirley Chisholm’s living room, Lynch began playing the video and sat back to observe Chisholm’s reaction. Prim and proper, sitting upright with perfect posture, Chisholm initially refrained from revealing much emotion. Soon, however, a gleam came into her eyes as the old campaigner began reveling in her younger self’s impassioned pursuit. Leaning forward in her chair, talking to her onscreen image, chiding herself for some things, nodding emphatically in agreement with others, Chisholm suddenly seemed transported back to her campaign days.

“It really was incredible,” Lynch says. “Occasionally, she’d giggle at herself onscreen and say ‘I said that?’ I got a running commentary the whole time. I really think she’d kind of forgotten how strong and outspoken she was then. It made it all worthwhile.”

Chisholm ’72: Unbought & Unbossed makes its PBS premiere Feb. 7 at 10 p.m. EST. For more information on the film, check www.pbs.org or www.chisholm72.net.