Beers for a Racist

J.W. Rich

At the mention of Lee Cody’s name, J.W. Rich’s face turns from ashen gray to angry pink. His lips twist into a snarl. He shakes loose a cigarette from his pack of Dorals, puts it to his lips, flips open his Zippo lighter and fires.

"I wish he’d walk in that door right now," Rich says. "I’d kick his ass."

At 63 years old, with a bad hip and a gimpy right arm, it’s doubtful Rich could inflict much damage. But the boast is safe. No one appears. "I hate that son-of-a-bitch," he adds. Then the moment passes. Rich’s face returns to its usual pallor. He settles back down to the beer sitting on the bar and takes a sip.

Despite a cold front moving across Northeast Florida, the bartender has propped open the front and back doors of the Triangle bar. Sheets of rain sparkle like tinsel in the streetlights on Old Lem Turner Road. The Triangle is a squat, one-story cinder block building on a stumpy stretch of road backing up to Lem Turner Road and Trout River Boulevard. It has burglar bars on the windows, and two pool tables and a dartboard inside. The dirt parking lot is full, and tonight every worn barstool is taken. On one sits a man with a greasy wad of brown hair matted to the top of his head and circles under his eyes so dark it looks like they were drawn with Magic Marker. On another, a middle-aged woman sits poured into a pair of blue jeans, her shoulder-length hair bleached into a blond flag of longing. A young man with a hatchet face and no front teeth mimes to the country tunes on the jukebox. For no discernable reason, he rises off the stool and steps outside in the rain, goes down on one knee and raises his arm skyward as if taking a round of thunderous applause from heaven. A man in a dress shirt and khakis leans morosely into the wall, his body deflated.

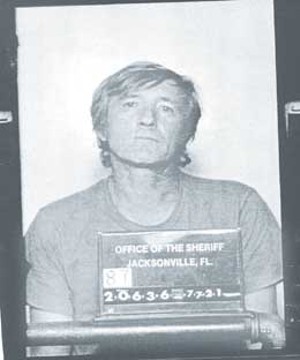

And then there’s Rich. He has his own hard-luck story. He’s still in love with the wife who left him because of his drinking (though he was drinking when he met her). He lost half his jaw and most of his throat to the cancer that attacked his lower lip. He can’t raise his right arm because the operation to remove his lymph nodes damaged the muscle. He spent three years in prison on a manslaughter charge for a murder he says he didn’t commit. And he’s spent the years since in and out of the Duval County Jail on a slew of DUI offenses. So now he’s drinking himself to death. He sits with the other solitary sentries before the gate of regret.

The Triangle has an improbable race-car theme, in the form ofBudweiser racing flags strung across the bar and NASCAR photographs on the walls. The television is perpetually tuned to a car repair show. But here you’re in the company of the broken-down and the stalled. The rules are simple. A sign tacked on the back wall informs patrons, "No Weapons Allowed." You can talk. Or not talk. There’s community if you want it. Or solitude. All blurred by the good graces of alcohol.

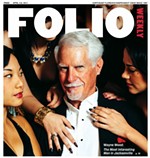

J.W. Rich is one of the regulars. To "Dateline" NBC, The New York Times, the Miami Herald, Court TV, even Folio Weekly, he’s the "shooter J.W. Rich," the cold-blooded trigger man in a notorious Civil Rights murder that remains an icon of injustice. But at the Triangle, Rich is a kind of mascot. He wears a camouflage cap with the name of the bar printed across the front. He shows up like clockwork at 10:30 a.m. and stays until early evening. While at the bar, he uses a special plastic beer mug the Triangle reserves for its marathon drinkers. It’s the size of a standard beer mug, but fashioned with an airtight compartment and filled with water. When the mug is frozen, the ice keeps beer chilled for extended stews.

"We love him here," says customer Donna Carter, who has known Rich for 20 years. "J.W. has a heart of gold. He’d give you the shirt off his back."

The bartender cracks open another $1.75 can of Busch and replenishes Rich’s mug. They take care of him here. He’s been drinking at the Triangle for more than 30 years. The bar stores a selection of jackets for Rich to use on cold walks home. If he’s low on cash, he asks the bartender to use his ATM card to make a withdrawal from the credit card machine. If he’s not there by noon, someone calls his house. When Rich comes back from a bathroom break, he points at his barstool. "This is where you’ll find me," he says with defiant bravado. "Every day by 10:30 a.m. with a beer in my hand."

The reason J.W. Rich wants to kick Lee Cody’s ass is because the former Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office deputy helped solve the murder of Johnnie Mae Chappell in 1964 and has refused to let the case die. If detectives Lee Cody and Don Coleman had not been involved, it’s doubtful anyone would remember Chappell’s name. She certainly wouldn’t have become a martyr of Jacksonville’s barbarous Civil Rights history.

Chappell was gunned down on New Kings Road at about 7:40 p.m. on March 23, 1964. According to a statement Rich gave sheriff’s deputies on Aug. 11, 1964, and statements from two of his three accomplices, Wayne Chessman and Elmer Kato, the men met up at a local diner with a fourth man, James Alex Davis. (Davis was sent overseas with the armed forces after the crime and did not give a statement.) They piled into Kato’s Plymouth to ride around town, and heard news on the radio of a race riot that had erupted in downtown Jacksonville. There was a gun on the front seat of Kato’s car. "Let’s get a nigger," someone suggested. With apparently little discussion, the men drove up New Kings Road on the Northside, looking for a victim.

They found Johnnie Mae Chappell. Having made dinner for her 10 children, Chappell walked to a nearby store to buy some ice cream for dessert. On the way home, the paper sack she carried became soggy and broke. At home, Chappell realized she’d dropped her wallet. She went back out to search the side of the road and a couple of neighbors joined to help.

According to Rich’s statement, Kato was driving along New Kings Road when the men spotted three blacks in the right-of-way. Rich admitted picking up the gun and firing out the window. Both Chessman and Kato agreed with this version of events, Cody says. The only difference between the versions is Chessman and Kato claimed Rich made the remark, "Let’s get [or kill] a nigger," and Rich claimed "someone" said it.

After Cody and Coleman obtained the three men’s confessions, they were able to track the murder weapon through several hands and retrieve it. They did this all on their own, without having been assigned to the case. In fact, no one was assigned to the case. It was a measure of just how little the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office valued the death of a black woman: Her murder wasn’t worth investigating.

Soon after obtaining the confessions, the detectives were ordered to stop their investigation. Cody isn’t sure anything else was done to develop the case, but on Sept. 25, 1964, a grand jury indicted all four men on the evidence.

Rich was the first to go on trial. He says now that the prosecution didn’t have anything on him. It’s true that the case may have looked slim to a jury. The .22-caliber gun that Cody and Coleman recovered was never introduced at trial (it later disappeared from the evidence room). Cody himself wasn’t called to testify. The other men’s statements weren’t submitted in court. The bullet taken from Chappell’s body was introduced in a plain white envelope, not an evidence bag showing the date it had been recovered and from where. Perhaps unwilling to press for a first-degree murder charge in the death of a black woman, the prosecutor told jurors they could find Rich guilty on a lesser count. The jury found him guilty of manslaughter and the judge gave Rich 10 years. Then the State Attorney’s Office released Chessman, Kato and Davis from prosecution for lack of evidence, despite their confessions.

For Cody and Coleman, the Chappell murder was the beginning of the end. Within a year, both men had been fired from their jobs. By that time, they’d assembled an impressive dossier on corruption and wrongdoing in Jacksonville Sheriff Dale Carson’s administration. They gave the information to Gov. Haydon Burns and the FBI, but nothing happened. In 1967, they reported the same information to Gov. Claude Kirk. In 1978, they gave it to Gov. Reubin Askew. And in 1979, they gave it to Gov. Bob Graham and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. Then they gave up. And the murder of Johnnie Mae Chappell faded into obscurity.

But in 1995, Cody happened to see a copy of the Florida Times-Union and notice a picture of Johnnie Mae Chappell’s youngest son, who’d organized a memorial service for his mother. Shelton Chappell was just 3 months old when Johnnie Mae Chappell was murdered, and he and his siblings were scattered into foster care. Shelton had taken a leave of absence from work in Miami and returned to Jacksonville in an effort to reunite his nine brothers and sisters. At that point, the Chappell children only knew sketchy details of Rich’s trial and conviction. Cody resolved to go to the memorial service and tell Shelton what had really happened.

It was that meeting, more than 31 years after Chappell’s death, that made her murder a political and emotional flashpoint. Since then, the Chappell family, led by Shelton, has pressed for justice. They want to see the three men who were never prosecuted for their mother’s murder brought to trial. There is no statute of limitations on murder, and similar delayed prosecutions in Alabama and Mississippi have been successful. With the help of some politicians — particularly Jacksonville Sen. Tony Hill — and the pro bono work of a powerful downtown law firm, the family has urged Gov. Jeb Bush and State Attorney Harry Shorstein to convene a grand jury, because only a grand jury can return a first-degree murder indictment. (The FDLE completed an investigation, ordered by Gov. Bush, last week.)

No matter what happens, Rich won’t be punished. He can’t be tried again. "They don’t want anything with me," he says. "They ain’t after me."

Still, he can’t live down the crime. His name appears in newspaper accounts and television broadcasts every time Shelton or Cody is interviewed. Reporters hound him for comment. His house has been egged. One of Rich’s friends at the Triangle says Rich is occasionally overcome by the pressure. "I’ve found that man right there in here crying, because he just wants this to be over with."

Rich could blame Cody for stirring things up, but his hate runs deeper than that. Rich claims Cody bullied a confession out of him. He says Cody smacked a blackjack on the table. He says the detective pulled a gun on him and held it to his head. He says Cody told him he could shoot Rich dead and get away with it. That, Rich claims, is why he confessed. "I’d rather be in prison than dead," he says.

Told about Rich’s allegation, the former detective snorts. "Anybody who’d believe that is a stone-cold idiot," he says. Cody points out all three men told the same basic story and that they didn’t have time to confer. It was an almost perfect case. The outcome? "It was an abrogation of justice."

Finding Rich is easy. His Riverview address is listed in the telephone book, and he spends roughly eight hours a day on the same barstool. But he’s learned to watch out for the media. He doesn’t answer his phone. The chain-link fence around his property is secured with a padlock. And a sign warns, "No Trespassing. Dog. Stop."

On an early October afternoon, as a flurry of media responded to news that the law firm of Spohrer Wilner Maxwell & Matthews was representing the Chappell family pro bono, Rich’s neighbors are out in their yards. Most are his kin. His ex-wife, who lives a few doors down, suggests that Rich is probably home, just passed out cold. He drinks all day, she explains. "Try him in the morning. He’ll be there then."

But Rich’s blue-gray, asbestos-shingle home seems empty. The faded Confederate and American flags hang limply in his yard. A bellowed "hello?" from the street draws no response.

The closest watering hole seems a likely spot to look for Rich. On his perch in the Triangle, he’s amused at a journalist’s stammered introduction. Rich listens calmly to a fumbling request to discuss the Chappell murder, seeming to enjoy the show. "Well, if we’re going to talk," he says finally, "sit down and buy me a beer."

In subsequent meetings, Rich makes it clear that the people in the Triangle think he’s a nice guy. He wants me to talk to other patrons. "Ask anybody," Rich says, gesturing at the others. "Not one of them has a bad word to say about me." He calls to the bartender. "Donna, come over here." She’s a no-nonsense woman in her early 40s with waist-long honey-blond hair. He asks her to explain what he’s like. Donna has known Rich since she was 14. Her father fished with Rich, and both are regulars at the Triangle.

"What do you want to know?" she challenges. "A lot of people say he’s an asshole," she adds, allowing a couple of beats before she continues. "But that’s 'cause he speaks his mind." She turns to Rich. "Right?" she asks. "People say I’m an asshole, too. Don’t they? Don’t they?"

Although Rich explains he’s the kind of guy who will stop to help someone with a flat tire — "green, yellow, brown, black or purple" — he tosses the word "nigger" around freely. He calls Johnnie Mae Chappell, with some deference, a "black lady." But his neighbor who plays his car stereo at 5 a.m. is a "nigger." So is any young black man who wears drooping pants.

Such sentiments don’t raise an eyebrow among his friends. And for the white patrons of the Triangle, believing Rich’s version of the Johnnie Mae Chappell story is about loyalty. Rich, perhaps bolstered by their credulity, wants to test his story on a larger audience. He says he wants his name cleared. "I didn’t kill that woman!" he exclaims furiously.

If Rich wants to make his case, it would be a change. He’s done his best to dodge the media spotlight for the past few decades. Even when he’s had to appear in public, like when he was called by the State Attorney in October to discuss the Chappell case, he’s moved quickly and kept a low profile. (The State Attorney let him use a back door to elude the media after he gave his statement.) Rich pulls a smeared voter registration card out of his wallet. He wants to be able to own a gun, to vote, to be a full citizen again. A Republican, Rich says he’d have voted for Bush in 2004 if he could have. This stuff plays well among his bar buddies.

"He didn’t shoot that woman," one of them says. "Not the man I know. He couldn’t have done that." Their reasons are his reasons. He was too far away from Chappell when he fired to have shot her. The bullet didn’t match the gun introduced into evidence. The four friends threw the real gun into the Trout River, where it is probably sunk in three feet of mud.

Talking about the murder angers Rich. "It’s bullshit, bullshit, bullshit," he says. "I’m sick of this. It’s been going on for 41 years. I lost my family over it. All the credit I built up was ruined."

Rich’s current version of events differs markedly from the one he gave deputies in 1964. He denies he fired the gun — he says one of the other guys did — and insists even that happened some six blocks away from the murder site. The four friends were shooting at a sign, not a person. Rich claims he heard the "ping" of the bullet on metal, so he knows it hit a sign. He also says that, while in prison, a relative of Johnnie Mae Chappell told him that Chappell was really murdered by her husband. He says he didn’t even know there were race riots in Jacksonville that night, and that the guys in Kato’s car weren’t listening to the radio. Maybe he’s said it so many times he believes it.

"My daddy told me if I killed her, I should take my punishment," says Rich, who’s father is a minister in a Holiness church in the area. "And if I didn’t, God would take care of me." Rich says he’s still waiting on God to make it right.

Donna walks over to Rich. "Jukebox?" she asks. Rich pushes two dollar bills toward her. "Play 47-16," he says. He laughs at the idea that he’s been in this bar so long he knows the songs by their numbers. 47-16 is one of his favorites: "Man of Constant Sorrow."

Retired Duval County criminal court reporter Leo Powell doesn’t remember J.W. Rich’s confession quite the way Rich tells it. According to Powell, Rich was sobbing uncontrollably the night he gave his statement. "I felt sorry for Rich," he says. "He didn’t look like a murderer to me. It was just pure remorse. He was crying like a baby. He kept saying he didn’t mean to kill anybody."

Although Powell had been called to the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office only to take Rich’s statement, he says the situation made him uncomfortable. The 22-year-old was so beside himself he was ready to confess, but he hadn’t spoken to an attorney. Before he agreed to take the young man’s statement, Powell says he asked Rich if his family had a lawyer. Powell called attorney Wayne Ripley himself at 1 a.m., and Ripley told Rich not to say anything — that he’d see him in the morning. But before Rich left, detectives Cody and Coleman spoke to their suspect again. When they were done, Rich announced he wanted to talk. Powell warned Rich that detectives were looking to put him in prison for life or to put him to death in the electric chair, but Powell says Rich’s response didn’t look like fear to him. "I did it," Powell remembers Rich saying. "I did it. I didn’t mean to kill her."

After he took Rich’s statement, Powell had nothing further to do with the case. Which was strange. It was the only time in his 28-year career as a court reporter that he wasn’t called by the prosecution to testify that the statement introduced in court was accurate. Nor was he questioned by Rich’s lawyer.

"I would have been the best friend that boy could have had," he says. "I would have told the jury how remorseful he was."

The fact that he wasn’t called to testify is one of the reasons that Powell believes, like Cody and Coleman, that the case was rigged on behalf of Rich and the other men. He points out that the entire file of the Rich trial disappeared from the Duval County Courthouse. Cody discovered it missing when he began compiling records to help Shelton Chappell. The only reason Rich’s statement resurfaced recently is because Powell told a television producer that it was among the court documents in Rich’s federal appeal. At an appeal hearing several years after his manslaughter conviction, Rich tried to say his statement had been taken improperly. Powell testified to what lengths he’d gone to make sure Rich’s rights were protected. The judge denied the appeal.

"If you see him," says Powell, "tell him I said hello."

But after talking freely about the murder on a couple occasions and even offering to recreate the route of his notorious night ride, Rich clams up. Having spent the day at Shands getting his hip X-rayed, he’s not interested in conversation. "Not in the mood," he says angrily. "I talked to you already. Now get out of here."