Stevie Stiletto Isn't Dead

Walter Coker

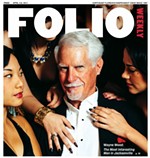

Ray McKelvey, former mad dog of punk

On July 6, following a night of hard rocking and a lifetime of hard drinking, Ray McKelvey headed home for some much-needed rest. He wasn’t feeling great. He’d been drinking all day and performed two shows — one in 100-degree heat and another in a smoke-filled club. Earlier in the evening he pissed blood, but being an alcoholic, he’d dealt with that before. A little cranberry juice, he thought, would clear that right up.

He awoke the next morning looking like some demonic parade balloon. His skin had turned bright yellow, and his twiggy frame had inflated to twice its normal size. He was so large and in so much pain that he couldn’t move. McKelvey’s drummer, who was rooming with him at the time, found the bloated vocalist and rushed him to the hospital, where doctors stabbed large needles into his abdomen to drain the collected fluid.

The doctors told McKelvey his liver was destroyed, and he was likely beyond treatment. They gave him a choice: Remain in the hospital for observation or go home. Either way, he’d probably be dead in a few days. McKelvey returned to his Westside Jacksonville trailer to die among his family and his beloved dogs. That was a year ago.

Ray McKelvey has never been one to worry about what people think of him. In fact, he couldn’t give a rat’s ass. As leader of the influential Jacksonville punk band Stevie Stiletto and the Switchblades, McKelvey has spent his career building a reputation as "An American Asshole," as one of the band’s albums is titled. For McKelvey, bad publicity has always been fabulous publicity. But lately, rumors have him concerned.

Word on the street varies. Some say McKelvey has cancer. Others believe it’s AIDS. Some say his stomach has been devoured by disease, that his guts are so deteriorated that the blood he pissed was actually bits of his liver. (The last one is close, but not entirely accurate.)

The truth isn’t much better. McKelvey has Hepatitis C and a terminal case of cirrhosis of the liver. He’s off the booze, has been for a year, and even kicked a heroin addiction, but now has a new chemical regimen. He ingests a stew of pharmaceuticals daily and hopes to be, by this time next year, to candidate for a liver transplant. But he must first wipe out the hepatitis — no easy task, but not impossible either.

Despite his illness, McKelvey hasn’t stopped working. A new Stiletto record, titled "My Life is Great," is due out in a couple of months. He still performs regularly and works in the studio with several side projects. He’s even participating in a new documentary about Stevie Stiletto. To hear him talk about it, rock-and-roll just might save his life.

Ray McKelvey emerges from his trailer’s boarded-up Florida room wearing patchwork cutoffs and showing a gap-toothed smile. His sleeveless shirt reveals arms black with tattoos, which only accentuate his ashen fleshtone. Shoulder-length black hair swings against his sunken cheeks as he lurches forward and, momentarily, he looks less like a rock star than Nosferatu. But he is gracious and jovial, with a self-deprecating sense of humor. He cracks wise about the broken starter on his Honda Civic and how he spent the better part of the day trying to get the goddamn thing running.

Located on Old Middleburg Road on Jacksonville’s Westside, McKelvey’s single-wide looks like any other. Aside from the homemade peace sign in the front yard and a mailbox decorated with black-and-white skulls, the place is unremarkable. Inside, however, the mobile home is a veritable punk-rock funhouse.

Every surface, every shelf, every table is crammed with skulls, dolls, masks and action figures. Every inch of wall space is covered with posters, concert fliers, paintings, newspaper clippings and photographs. All of the furniture is painted black.

The interior is as dark as a crypt. Sunlight struggles through the front-room window, the only natural light permitted into McKelvey’s lair. Every other window and door is covered. The purpose, says McKelvey, is twofold. "For one reason, we used to practice here, and it cuts way down on the sound," he says. "The other is, I’ve got real creeps for neighbors."

A few steps down the hall is a room full of classic guitars — only a portion of his collection (the rest are at his mother’s house) — and at the end of the hallway is McKelvey’s bedroom. Ramones memorabilia, Alice Cooper dolls and dinosaur figurines rise behind a four-poster bed, which has been fitted with handles above the headboard. No fetish fancy: McKelvey needed the handles during his convalescence to lift his frail frame from the mattress.

At the opposite end of the trailer is the kitchen, the most foreboding of all the rooms. This is McKelvey’s dead rock star shrine. Obituaries line the walls of the tiny kitchen — Johnny Cash, John Entwistle, Wendy O. Williams, Waylon Jennings, Sid Vicious, Janis Joplin, Dee Dee Ramone, Kurt Cobain, John Lennon. The list is endless, a collection McKelvey started long before death came looking for him.

McKelvey’s obsession with rock-and-roll — rock stardom, to be more precise — started early and never waned. Born in Chelsea, Mass., in 1956, he moved to Jacksonville with his family in 1959. In junior high school, under the influence of the Beatles, he and childhood pal Frank Phillips stole their sisters’ white go-go boots and painted them black to match those of their mop-topped heroes. They started a cover band called The Invaders, with McKelvey on drums and vocals, and performed songs by the Beatles, the Dave Clark Five and The Animals, along with some originals.

In his mid-teens, while attending Lee High School, McKelvey discovered the original goth-rocker, Alice Cooper, and his life changed. His vocation, he realized, was to be the showman, the ringleader. "I wanted to be Alice Cooper," recalls McKelvey.

After graduating in 1974, he kicked around in cover bands, playing local clubs, picking up groupies and, of course, imbibing.

By the end of the ’70s, punk and glam rock had emerged from the streets of London and New York — a stiff middle finger to both the arena rock of Led Zeppelin and the vapid disco movement. McKelvey was one step ahead of the game, a fan and admirer of Brit glam-punker Alex Harvey and his Sensational Alex Harvey Band years before the Sex Pistols hit the scene. "I think he was probably the original punk rocker," says McKelvey.

Tired of playing covers and craving recognition, McKelvey combined his love for theatrics with his passion for punk and, in 1983, formed Stevie Stiletto and the Switchblades.

The chronology of Stevie Stiletto is convoluted, a series of closely related bands that changed members as often as they changed names. The common thread has always been McKelvey.

Stevie Stiletto originally came together in 1983 and released the album "13 Hits and More." The early years were important for McKelvey as he began to shape his stage persona, but it wasn’t until the mid-’80s that the band reached its stride.

By 1985, guitarist Thommy Berlin joined original members McKelvey, bassist Mike Butler and drummer Rob Akk, and the band hit the road in support of two EPs and a full-length album. They toured the country in a 1959 Ford schoolbus — painted flat-black and decorated with skulls and bat wings — playing packed club shows in the U.S and Canada. These were the band’s salad days.

Managed by Indianapolis promoter and former Zero Boys manager Bill Levin, Stevie Stiletto lived what McKelvey calls "the rock star life," hanging in the best hotels, and opening for and touring with some of the biggest names in punk and metal: The Ramones, the Dead Kennedys, Motorhead, Megadeth, Bad Brains, Iggy Pop, Circle Jerks, the Flaming Lips, G.G. Allin, the Descendents and a host of others.

In this company, McKelvey unleashed his dramatic inclinations, creating a stage show that included exploding shaving-cream cans, fire extinguishers full of ice water and fake speaker cabinets that he would throw into the crowd.

The music, a combination of Southern rock, punk and speed metal, complimented McKelvey’s on-stage antics. He carried himself like Patti Smith, strutted like Elvis and sounded like Black Flag-era Henry Rollins. All this, capped with clown masks and fueled by alcohol, meant anything could happen at a Stiletto show. "I’ve [chain]-sawed a surfboard in half," says McKelvey. "And I walked on stage in San Francisco [wearing only] gold-sparkle cowboy boots and a glow-in-the-dark Glowworm rubber."

But in the finest rock-and-roll tradition, just when things were looking up for the band, it all fell apart. After another Stevie Stiletto lineup change, Levin’s father died, taking him away from management duties. The band persevered, trying to book their own hotel rooms and battling club owners for payment, but they were scraping by. After a show at The Electric Banana in Pittsburgh, McKelvey recalls, Sonic Youth bassist Kim Gordon slipped him a fifty so the band could buy gas to drive to the next gig.

It was during a late-night drive from a gig at CBGB in New York City to a concert in New Brunswick, N.J., that the band’s luck failed completely. The vehicle carrying drummer Dan Limerick and stage tech Steve Pratt smashed into an unlit tractor-trailer stopped dead on the highway. Equipment was all over the road and the bodies of the band members were bloodied and broken when McKelvey and Butler arrived on the scene. Through no one was killed, it looked like it might be the end for Stevie Stiletto.

McKelvey pressed on. By 1988, after another lineup change and a move to Indianapolis, then San Francisco, the band angled for a fresh start. Stevie Stiletto released "Pin Ups," a cover album that mimicked David Bowie’s recording of the same name, and "Smell the Sock," a parody of Spinal Tap’s "Smell the Glove," which was recorded months before by engineer Jim DeVito at his studio in Crescent Beach. The band hired porn star Lotta Top to pose nude on all fours and sniff a sweat sock, the punk version of the Spinal Tap cover that never was.

But as the band moved closer to success, McKelvey’s heroin/crystal meth addiction complicated growing tension within the band. By 1992, McKelvey decided to leave the band, load up his dogs and his equipment, and try to kick his habit on a cross-country drive. After three days on the road with no dope, he ended up back in Jacksonville, where he continued to dry out — or at least stay off the horse. In town, McKelvey hooked up with bassist Pat Lally (now proprietor of Nicotine in Five Points), drummer Tim West and McKelvey’s childhood chum Frank Phillips on guitar. The band adopted the moniker Ray Ray, which morphed into Continental Ray Ray, Ray Ray Rocks and Hurricane Ray Ray. Throughout the early ’90s, the band played locally and released another record, but it wasn’t until McKelvey and Phillips reformed Stevie Stiletto with drummer Neal Karrer and Lorne Mays (the current configuration) that things picked up again. The band released "Back in Arms" (one of McKelvey’s favorites) and "An American Asshole" on Attitude Records. The albums sold well and were distributed internationally, and a European tour followed.

But the band never caught the momentum of earlier lineups, finding more success overseas than in America. The ever-manic McKelvey also formed other side projects, including El Kabongs, which performed punk and metal versions of classic rock tunes in Jacksonville and Orange Park. It was after a performance with El Kabongs that McKelvey first shook hands with the Reaper.

Frank Phillips looks more like a Jaguars season-ticket holder than a punk-rock guitarist. Heavyset, wearing a football jersey and backward baseball cap, Phillips readies his equipment for rehearsal.

Though attached to a respectable marshfront home near Jacksonville Beach, the rehearsal garage reeks of rock-and-roll. Holiday lights dangle from the ceiling, concert posters cover the walls and a window unit coughs out just enough air to keep a Florida July day at bay.

The P.A. speakers blast Primus as the members of Stevie Stiletto file in. Drummer Neal Karrer gets his kit squared away on a platform along one wall while Lorne Mays straps on his bass, then wraps a bandana around his right wrist. He smacks a pack of cigarettes against his palm, opens it and lights one up, the smoke mingling with the odor of sweaty men.

While fiddling with his guitar, Phillips accidentally knocks over what he believes to be a cup of spit. "I don’t know what it was," he says. "Something nasty." This leads to a conversation about Phillips’ saliva-covered microphone and its unpleasant aroma. Olfactory memory kicks in and the guys are soon discussing music, the road and Ray McKelvey.

"Ray’s really changed since he quit drinking," says Phillips with a sly grin. "He actually hits the notes now. Now he really sings good." Phillips adjusts his microphone, and his tone deepens. "It’s definitely a different Ray. When you’re gonna die, I guess it’s time to quit drinking."

If Phillips sounds flippant about McKelvey’s condition, it’s not out of insensitivity. Phillips and McKelvey have known each other since the sixth grade. They’ve shared the happiness and hell of full-time musicianhood, and have both matured beyond their reckless early years. Humor has always been a part of the Stiletto performance ethic, and the ribbing is a sign that everything is running as it should, just like the old days.

The old days dominate the conversation. Before launching into their rehearsal set, the boys reminisce about hard partying, road chicks and past shows. McKelvey shamelessly boasts about his former stage persona, an inebriated punk-rock circus clown who just might whip out a .22-caliber pistol and fire at balloons in a nightclub. (The bullet wound up lodged in the women’s room wall, just inches from a customer’s head.)

"I don’t care," says McKelvey. "I would take a shit on stage." Like his childhood idol Alice Cooper, once rumored to have done so, he never did.

Truth is, McKelvey rivaled the best performers in the world of punk. According to Thommy Berlin, former guitarist for Stevie Stiletto, McKelvey belongs among the legends. "Lux Interior, the singer for The Cramps, was the best frontman I’ve ever seen. Next would have to be Iggy [Pop]," he says. "I tell ya, man, there were nights that Ray was up there [with those guys]."

Such praise doesn’t come easy from Berlin, who made his mark on the Jacksonville music scene in the decade he performed with Stiletto as well as with his own bands, Radio Berlin, Velvet Elvis, Evil Maracas, and Thommy Berlin and His Big Head.

Berlin met McKelvey through a mutual friend in ’85, joined Stevie Stiletto soon after, and left the band by ’88. What happened in between, some believe, was the greatest Stiletto lineup of all. "A lot of people think that the recordings that we made, and that particular band, was the best one," says Berlin. "I don’t know that that’s true, but I hear it a lot."

During Berlin’s tenure, Stevie Stiletto released the EP "It’s a Bogus Life," which McKelvey claims made it into Billboard Magazine’s Top 30 best independent albums the year it was released, and the classic "Food for Flies." It was a productive — and destructive — time for the band.

McKelvey and Berlin shared more than just music. They were fellow addicts. While McKelvey ingested massive amounts of alcohol, Berlin shot heroin. Though their addictions rarely got in the way of the music, it was the beginning of the downhill slide for both men.

"I was the dope addict in the band. Ray was the drunk," says Berlin. "The fact that Ray lived to be 26 was awfully surprising. It really was."

In the early days of punk, the Sex Pistols’ anarchical "No Future" ethic was very real to the members of Stevie Stiletto. But what began as a pseudo-nihilistic political statement pushed by a London boutique act became a way of life for Berlin and McKelvey.

To illustrate this point, Berlin relays an anecdote about a trip from Jacksonville to a gig in Miami. He and the band left town in a borrowed car with 100 hits of speed and arrived in Miami with nothing. "I remember flying the station wagon off the fucking off-ramp," Berlin says with a sinister chuckle. "I mean just totally missing the road, you know. Fried out of my gourd."

For many years, Berlin chose dope over music, and it nearly destroyed him. But he says he’s cleaned up and is working on new music. He just picked up a new guitar and plans to record again soon. And he hasn’t ruled out the possibility of working with his former bandmate, but doesn’t think he could ever perform with the new Stiletto lineup.

"The Stevie Stiletto, the band I was in, we were a bunch of weirdoes who were really doing our level fucking best to be normal," says Berlin. "Today’s Stevie Stiletto are a bunch of real normal guys that are doing their level best to be weird."

A subversive mind in corporate America, Doug Milne Jr. keeps an office in St. Augustine’s World Golf Village. On his desk rests a Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds CD. On his corkboard, a Rollins Band poster. The incongruity is almost funny, a corporate shirt at the PGA digging underground rock.

A table before a television monitor is full of videotapes, images from Ray McKelvey’s life. Milne, a PGA Tour Productions’ promotional video producer, has of late been obsessed with the life and work of Ray McKelvey. A punk fan from way back — he used to attend early Stevie Stiletto shows and eventually became friends with McKelvey — Milne wanted a break in his corporate video routine.

"All the stuff I’ve done, writing and producing-wise, has pretty much been for golf," says Milne. "[But] there’s that creative side. [I] don’t want to do just golf, so [I] have little side projects."

After learning McKelvey was ill, Milne decided to document the life of the forgotten punk hero. Milne contacted McKelvey, who even after his life-draining battle with hepatitis and cirrhosis, was still hungry for the spotlight.

To both men’s surprise, people came out of the woodwork to lend a hand. McKelvey’s old friends volunteered to be interviewed, Milne’s co-workers offered to assist in editing, strangers asked to score the film. The help is appreciated, says Milne, calling it a "no budget" project.

Milne has shot 25 hours of material thus far, and has collected archival items — concert tapes, home videos, photo albums — from McKelvey’s personal collection. Cooperative as McKelvey has been, however, he has his own ideas about the film’s direction.

"One thing that I’ve tried to make clear to Ray, is he’s under the impression that [the documentary is] just about the days of the band," says Milne. "But I think a very important part of this, I mean the initial draw, to me, was not the band. The initial draw, to me, was: Here is a guy that is facing a really harsh reality.

"He should have been dead a year ago, over a year ago, and he’s not," Milne continues. "He’s never given up on the band. Here he is 48 years old, he can barely get around, he’s got no working organs whatsoever, and he still wants to get up on the stage and play."

For all of the support Milne has received in putting his film together, there are the naysayers, people who don’t see the point in glorifying an alcoholic who did himself in.

"[My wife] doesn’t quite understand — why Ray?" says Milne. "Honestly, a lot of people have asked me that. My brother-in-law, he’s like, ‘Why Ray? The guy’s washed up. They’re done, man. People have forgotten all about him.’ I say I am doing this for me.

"If it doesn’t go anywhere, it doesn’t go anywhere," says Milne of the documentary. "But I’ll get an incredible sense of satisfaction that I was able to do it, and it will be something for [Ray’s] family and friends to have."

Hepatitis is an unforgiving foe. The blood-borne viral infection attacks the liver, and in the case of Hepatitis B, can be fatal. Hepatitis C, which McKelvey has, is curable (Pamela Anderson and Naomi Judd both have it), but requires strict medical supervision. Couple the disease with cirrhosis, and you’re pretty well screwed.

Such is McKelvey’s plight. Now off dope and alcohol, the former mad dog of punk is tethered to a tightly regulated diet, a slave to his medication and weekly doctor visits.

Though most would assume, justifiably so, that McKelvey picked up hepatitis from a dirty works while injecting heroin, he insists he contracted the disease from a tattoo needle. Berlin confirms this, saying that particular tattoo artist passed the disease to many of his clients through contaminated equipment.

But McKelvey is far from bitter. He knows his self-destructive lifestyle is, in large part, responsible for his condition. He has no regrets, save the fact that he treated his body like a cesspool and that his family is suffering along with him.

McKelvey’s mother, 80, has already lost one son. In 2000, McKelvey’s brother James Paul McKelvey died from complications of anorexia at 33. A talented sculptor who worked for Jacksonville-based amusement park dark-ride designer Sally Corp., James Paul became depressive and reclusive, and died a mere skeleton. After his brother’s death, McKelvey salved his pain with alcohol. He did the same after his two divorces, especially the second, which occurred just after Stevie Stiletto returned from their 1997 European tour.

"I started really drinking hard," says McKelvey. "I wasn’t happy [during that marriage]. I was working my ass off landscaping. Out in the sun every day working your ass off, come home to a drunk wife and dirty house. It wasn’t fun."

McKelvey, who’s been clean for 13 months, has since made amends with his ex-wife, Debra, mother of his daughter, Denise. He also spends time with his two grandchildren, Emerald and Derrick. In some ways, his illness has brought him closer to his family. All of his five sisters have offered to donate part of their livers for transplant — that is, if McKelvey makes it through his hepatitis treatments, which will be complete in April 2006.

But a transplant may not be necessary. McKelvey’s doctors recently contacted him with good news. They found evidence to suggest his liver may still repair itself. He was heartened at the prognosis, but remains prepared for the worst. "I already did the living will and the whole nine yards," he says. "I’m still definitely terminally ill. I’m fine with it."