Going Negative

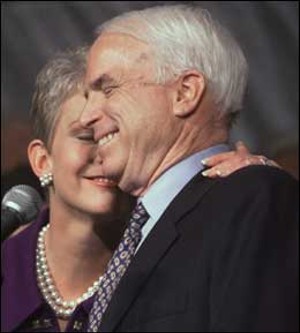

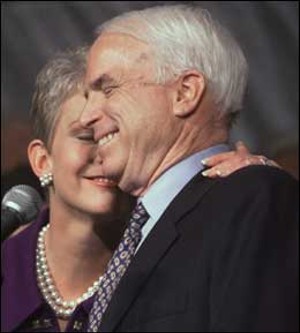

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

John McCain gets a hug from his wife Cindy after losing the South Carolina Republican presidential primary in 2000.

In 2000, all the president’s men were calling Sen. John McCain unfit to lead after years trapped in a tiger cage, claiming his wife was a junkie, and alleging the McCains’ adopted daughter was actually the senator’s illegitimate child.

Four years down the line, the opponent has changed, but the tactics remain the same. Witness the portrayal of John Kerry, a decorated war hero, as soft on defense and a welcome mat for international terrorists (see Quote).

Beaufort Mayor Bill Rauch has seen it all before, first as an advance man and press secretary for former New York Mayor Ed Koch, and later as a McCain campaigner in 2000. In his recently released book, Politicking: How to Get Elected, Take Action, and Make an Impact in Your Community, Rauch devotes a chapter to how he witnessed the McCain smear campaign and, in an interview with the City Paper, compares and contrasts it with what the senator from Massachusetts is facing today with the Swift Boat campaign.

In a chapter entitled “Principle,” Rauch writes that going into South Carolina, the two Republican candidates were in a dead heat, McCain having upset Bush in the New Hampshire primary. Knowing the vote would be close among traditional Republican voters and McCain’s “antiestablishment” draw would attract independents and crossover Democrats, the Bush campaign focused on conservative religious groups like the Christian Coalition, mainly in South Carolina’s Upstate.

Bush and his campaign manager, Karl Rove (who also heads Bush’s current campaign), recruited the likes of televangelist and one-time presidential candidate Pat Robertson and Ralph Reed, former executive director of the Christian Coalition.

According to Rauch, Robertson’s and Reed’s jobs were to “demonize McCain to these 250,000 voters while making sure the fingerprints of the job didn’t get tracked before primary day.”

Rumors circulated amongst Christian talk radio jocks and accusations were made via flyers, prerecorded phone calls and e-mail, Rauch writes. The smear campaign attacked McCain’s mental health, saying he was “psychologically unbalanced from being in Viet Cong prison camps for seven years,” Rauch writes. It was also alleged that McCain’s wife, Cindy, who had disclosed that she was once treated for depression, was a drug addict.

“McCain campaign workers also found workers, who would not say for whom they worked, placing a flyer under churchmembers’ windshield wipers that alleged the same thing: that the senator was crazy after seven years in the cage and that living with him had turned his wife into a junkie,” Rauch writes.

Rumors also alleged that the McCain’s adopted Bangladeshi daughter, Bridget, was actually the senator’s illegitimate black daughter.

Attacking McCain’s support of stem cell research, prerecorded phone calls asked, “If you knew that Senator McCain had voted in the United States Senate in favor of using the fetuses of aborted babies for scientific experiments, would you vote for him?” Rauch reports in his book.

Other rumors attacked McCain’s views on the then-hot Confederate flag issue and even his sexuality — thousands of Christian conservatives were mailed a letter from what appeared to be a Baptist Church in Kentucky that raised questions about McCain’s sexuality and condemned “John McCain’s Fag Army.”

In all, Rauch writes, the Bush campaign spent at least $8 million in South Carolina in about three weeks according to its federal election commission filings.

“The turnout in the 2000 primary was the largest in South Carolina’s history. Exit polls showed that McCain beat Bush by a hair among Republicans who did not identify with the religious right, but that religiously motivated Republicans voted for Bush in such overwhelming numbers that he easily carried the day,” Rauch writes.

The questionable methods worked for Bush, which, Rauch says in a recent interview, is highly respected in political circles.

“This technique works very well; it probably won the South Carolina primary for Bush. McCain didn’t win because he wouldn’t lie to win. But most politicians are more respectful of winning than of the principles of the tactics involved.”

Now, in 2004, it appears the Bush campaign is at it again, attacking Sen. Kerry’s service in Vietnam. Attorneys and private investigators — who have been connected to Bush and his campaign manager, Karl Rove — interviewed dozens of Vietnam veterans who allegedly claimed to have served with Kerry. A few of the vets spoke out against Kerry, attacking the credibility of his service in Vietnam and the validity of the acts for which he received his medals.

“I’ve heard Bush say that Kerry is doing the same thing, but I don’t know of anything except questioning (Bush’s) National Guard service. But speaking on the record about something that’s on public record is different from hiring private investigators and interviewing 75 people, only to publicize what three or four of them said,” Rauch says. “If you talk to enough people, you can find somebody to say anything.”

Though the smear tactics seem to be working again for the president, Rauch says Kerry has a few advantages over McCain.

First, the attacks against McCain were spread via rumors among specific groups, so McCain had great difficulty even tracking down exactly what was being said, and therefore couldn’t really defend himself. Also, the attacks came just before the election, so even if McCain had been able to respond, he wouldn’t have had time.

The attacks against Kerry began with national paid ads, so he is aware of all that is being said. Also, the election is still two months away, so Kerry has time to fight the allegations. Rauch says in an ideal world Bush’s campaign would have held out until the last minute to release the Swift Boat information. But he feels the Bush campaign launched the attack early since the two were neck and neck going into the Republican National Convention.

When two candidates are in a dead heat, Rauch explains, that actually indicates that the incumbent is losing, since swing voters will often side with the challenger.

The other advantage Kerry has over McCain is Bush’s “negative percentage,” which represents the number of voters who will vote against Bush, but not necessarily because they like Kerry.

Since the Swift Boat ad campaign began, Kerry’s numbers in the polls have gone down, but Bush’s negative percentage has been steadily creeping up, according to Rauch.

In recent polls conducted by The Washington Post/ABC, Bush narrowly leads Kerry 48 percent to 47 percent (with Independent Party candidate Ralph Nader drawing 2 percent, 1 percent saying they wouldn’t vote at all, and 2 percent having no opinion). In recent polls conducted by FOXNews, Kerry edges Bush out 44 percent to 43 percent, with Nader receiving 3 percent, and 10 percent having no opinion.

“I think this election is Bush’s to win or lose,” Rauch says. “There isn’t anything Kerry is going to do to electrify voters to vote for him at this point. But voters will vote against the president. When your [negative percentage] is up, you need to be a nice guy and get it down. Having your campaign out there doing untoward things doesn’t help.”

Though Kerry still has a chance to rebound from these attacks, the negative publicity has caused visible damage, possibly enough to put Bush over the top once again.

Negative campaigning has worked so well for so many politicians that it has become an acceptable way to get elected. Still, there are politicians out there who refuse to stoop to that level.

“I certainly understand their effectiveness,” Rauch says, “but do I think it’s good for the process that the most important thing for a campaign to do is to tear apart the other person, whether the accusations are true or false? No. I don’t think it brings us the best leaders.”

So how can voters discern between truths and smear campaigns and get back to electing the best leaders?

One way, Rauch says, is to pay attention to the real issues and take the rest with a grain of salt. For example, if a candidate wants to talk about the budget and points out that his opponent intends to increase spending by creating additional programs, that’s fair game. But when candidates begin to attack their opponents’ characters and personal motivations, voters should take heed.

“Negative campaigning is going to continue to work until the electorate gets smart,” said Rauch. “Once you know how the game is played, then you get back to more candidates who support a community’s best interests instead of going negative as a way of getting elected.”