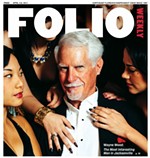

Daddy's Girl

Walter Coker/Folio Weekly

Surrounded by images of bloody mayhem, John Tanner sits quietly and takes notes. With the national media spotlight trained on the notorious Xbox murder trial, the state attorney for the 7th District of Florida seems determined to keep his focus on the case. But there are distractions. The full-page newspaper ads purchased by police officers, for instance, accusing Tanner of being on a “witch hunt,” and suggesting he’s using his position to get revenge. There’s also the embarrassment of getting removed from an investigation he initiated after the four sheriffs in his judicial district complained to the governor about his conduct. And, of course, there is the pressure of his family — particularly his daughter, Lisa, whose arrest for disorderly conduct and subsequent jail detention has become so notorious that a Google search of her name turns up not just numerous articles and video clips, but endless chat-room discussions alternately defending her and calling her an “arrogant spoiled ghetto brat.”

For Tanner, the distractions are already a nuisance. But they threaten to become a professional liability. Tensions between him and local law enforcement have reached a fever pitch. Some wonder whether he can continue to do his job effectively, or whether, given his divided loyalties, he should even be allowed to try. The crisis has also raised questions about his political viability. Though Tanner doesn’t face re-election for two years, he was drummed out of office once before in the early ’90s, and has little reason to trust the power of incumbency. Tellingly, his spokesperson declined to say whether he would run.

Perhaps most troubling for Tanner is the public perception that he has allowed his district to descend into chaos, jeopardizing the judicial process and tarnishing the reputation of law enforcement. State Attorney Harry Shorstein, who recently took over Tanner’s investigation at the request of the governor, says one of his primary goals is to restore a sense of order. At a press conference last month, Shorstein acknowledged the current circumstance is untenable.

“It at times raises the perception,” he said, “that things are totally out of control.”

The hand-held video is shaky. The audio is poor. But the tape’s quality doesn’t make it any less disturbing. Lisa Tanner’s March 24, 2005 jail detention is as unvarnished as a snuff film, and almost as shocking. Though it begins with petty demands from officers and equally petty resistance from Lisa Tanner, it culminates with a brutal struggle as corrections officers force the 30-year-old into a restraint chair. With four beefy officers holding her, the 114-pound woman struggles and screams. “I don’t know what you’re doing,” she repeats, her voice shot through with panic. “I don’t know what you’re doing.”

“Stop resisting,” an officer shouts over her. “Stop resisting.”

“I’m not resisting,” she shrieks. “I don’t know what you’re doing.” With the guards tightening the restraints, and one holding her head and neck, Lisa Tanner bucks and issues an agonized scream. Then she goes limp. She remains that way for 25 minutes.

It’s not surprising that the video aroused concern. What is surprising is that it became the launching pad for a wide-ranging investigation into abuses at the Flagler County Jail where Lisa Tanner was held — a probe that led to the indictments of several law enforcement officers and the removal of the jail’s director. The investigation also spread beyond Flagler County’s borders. State Attorney Tanner, who oversees Flagler, Putnam, Volusia and St. Johns counties, broadened the probe to include all four county jails.

Tanner’s critics — and they are legion — say he opened the investigation as an act of vengeance, in order to punish those who mistreated his daughter. Tanner denies this, and his probe has found other instances of prisoner mistreatment, including the use of pepper-spray on disabled inmates. But it’s equally clear that his daughter’s arrest was the driving force behind his interest in jail conditions.

“The violence that they inflicted upon my daughter alarms me,” he wrote in a March letter to Flagler County Sheriff Don Fleming, “and is good reason to not trust [the corrections officers’] judgment, or their ability to control their anger when dealing with citizens under their supervision.”

The police union counters that Tanner is on a “jihad.” They accuse him of working outside normal investigative channels to get the results he wants, and they specifically criticize his decision to solicit complaints about officers from local defense attorneys. In a June letter to every member of the Bar in his district, Tanner asked for help “find[ing] the undocumented abuses and those cases in which the evidence has been altered, destroyed or lost.” His law enforcement critics call the letter “ambulance chasing.”

The investigation has put Tanner at loggerheads with local police, upon whom his criminal cases depend. And the conflict has grown increasingly personal. Jim Spearing, an official from the state police union, says, “Mr. Tanner needs to spend more time disciplining his child and not persecuting our officers.”

Sheriff Fleming agrees. In his letter to the governor, he said Tanner “has lost all objectivity and has misused the auspices of his elective office while blurring the line between aggrieved father and public official.”

St. Augustine attorney Joe Miller, a former assistant prosecutor in Tanner’s office and a staunch ally, defends the state attorney as honest and forthright. But even he admits the conflict is causing damage.

“You want to know who suffers when the prosecutor and the law enforcement can’t get along?” he asks. “The people suffer. They get poor service. It’s absurd.”

John Tanner is politically conservative, an avid bow hunter, an Evangelical Christian. Throughout his career, he has enjoyed high-profile successes, including putting Aileen Wuornos, Florida’s only female serial killer, on Death Row. He also persuaded serial murderer Ted Bundy to confess to more than two dozen crimes — though he was widely criticized for praying with the killer in his cell.

Tanner is no stranger to controversy. In 1992, his zealous campaign against pornography cost him his re-election (though he won the seat back four years later). But while Tanner has made morality a key part of his public life, his family hasn’t always made this easy. In addition to Lisa Tanner’s two arrests in 2005 for disorderly conduct, she was investigated by police in 2002 over allegations that she’d stalked an ex-boyfriend (no charges were filed). Tanner’s grandsons, Matthew, Joshua and Chad Boda (known as the “Boda Brothers” to Flagler County law enforcement), have also generated dozens of arrests for alcohol, drugs and even burglary with assault.

For the most part, Tanner has managed to work his side of the law enforcement equation without getting bogged down by his relatives’ legal entanglements. But the Lisa Tanner video changed everything.

Lisa Tanner was arrested for the first time in March 2005 after a neighbor called police complaining of noise and drinking at 2 a.m. According to the police report, filed by Officer Nathaniel Juratovac, a high school classmate of Lisa’s, she initially resisted arrest, dropping herself to the ground. Two officers lifted her into the police car while she allegedly called them “fuckers” and “assholes.”

Once in jail, Lisa was a difficult inmate, according to a subsequent grand jury’s report. According to the jail log, she tried to flush her jail-issued shoes down the toilet and then urinated on the floor in the cell. She backtalked to guards and refused to comply with simple commands. After being placed in a restraint chair, she wiggled free of the straps and gave the middle finger to the camera. A muffled voice of a male officer can be heard on the tape, saying, “How the hell? I had those things fucking cranked.” Another voice says, “I can’t believe it.”

At that point, the four officers re-enter the cell and forcefully strap her into the chair. Sgt. Betty Lavictoire, the ranking officer, holds Lisa’s head by her hair and chin as the other deputies tighten the straps. (Lavictoire will later be charged with false imprisonment and battery.) Lisa complains that there is something wrong with her feet and they hurt. No one responds. After flailing and screaming for more than a minute, Lisa stops fighting, then stops moving. She appears to pass out. Skeptical, the officers tell her to “stop faking.” When she doesn’t respond, they spray her face with water and wave smelling salts under her nose. She doesn’t move. Finally, officers call paramedics, who unbuckle her and drag her limp body onto the jail bunk.

The video (filming is standard jail practice when force is used) seems brutal to the lay viewer. But did it not immediately strike law enforcement officials as wrong. After John Tanner, citing conflict, excused himself from the case, Gov. Jeb Bush appointed State Attorney Norman Wolfinger of Brevard County as special prosecutor. Wolfinger’s report to the governor concluded, “In our opinion the videotape did not show any act on part of any corrections officers that would constitute a crime.” In fact, a previous letter from Wolfinger’s office suggested Lisa send “a sincere letter of apology to Officer Juratovac and Corrections Officer Betty Lavictoire.”

It’s likely the issue — and the videotape — would have died had it not been for Lisa Tanner’s arrest in November 2005, for interfering in the arrest of a friend. Tanner again recused himself from the case, and this time Gov. Bush appointed State Attorney Jerry Hill from Polk County as special prosecutor. It was Hill’s decision to show the jail video to members of a grand jury. Their reaction was very different. In a scathing 12-page presentment, jurors called the videotape “grim and shocking.”

“We believe what was done to Ms. Tanner was just plain wrong,” they wrote. In addition to dropping all charges against Lisa Tanner, jurors noted that she’d received a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder from the detention. They ordered a DVD copy of the incident be made public, along with their report.

Because of the two prosecutors’ very different findings, Tanner’s critics contend he “shopped” for the right special prosecutor, pressuring Bush to investigate and personally mailing him a copy of the video. This allegation is included in a letter to Gov. Bush from Sheriff Fleming and the police union that outlines 29 points of “prosecutor misconduct.” The letter accuses Tanner of using his office to help Lisa’s private attorney build a civil case against the Sheriff’s Office (she filed an intent-to-sue notice in May). And they criticize him for inappropriately granting an interview to CBS News when he had a grand jury empanelled that he was supposed to lead impartially.

But Tanner, who has granted some interviews and denied many others,

appears torn between engaging the media and freezing it out. When asked to comment for this article, Tanner declined. According to his spokesperson Linda Pruitt, “it would be unethical because of the ongoing investigation.”

St. Johns County Sheriff David Shoar is in a tough spot. The former St. Augustine police chief and first-term county sheriff has managed to escape political entanglements for most of his 26-year career. But he now finds himself caught between the reputations of his prosecutor and his officers. In this case, Shoar decided to side with the cops, despite what he calls a 25-year friendship with Tanner. In June, Shoar joined the three other sheriffs in Tanner’s judicial district in complaining to Gov. Bush about Tanner’s conduct and asking that he be removed from the jail investigation. The governor did “discharge” Tanner (though Tanner claims he asked to be removed first) and assigned State Attorney Shorstein to take over the case. Bush also asked Shorstein to investigate Tanner’s handling of the jail probe.

In response, Tanner accused the sheriffs of erecting “the blue wall of silence,” implying that they are banding together — regardless of the truth — to protect the men and women in uniform. Shoar calls Tanner’s comment “very offensive.”

“It implies silence when it should imply honor,” says Shoar. “Myself and other heads in law enforcement have spent our careers putting bad cops away. It wasn’t a question of choosing the sheriffs or the prosecutor. It was a question of the truth.”

Chief Rick Look, who joined the Flagler County Sheriff’s Office after Lisa’s arrest, also once considered Tanner a friend. But the investigation has permanently soured that relationship. “The ‘Blue Line’ that Tanner refers to is one of honor, and John Tanner has lost his right to be part of it. … My position today is that he has no honor.

He’s ruined people’s lives. It reminds me of fascism.”

Such vehemence makes some skeptical that the rift can be healed. State Attorney Shorstein calls the situation “very unhealthy.”

“All four sheriffs [in Tanner’s district] went to the governor’s office to express their concern,” he notes. “Let me make it perfectly clear: I can assure you that we consider this a serious matter.”

Even when the investigation concludes, most think there will be lingering mistrust. “I think it’s sad,” says Shoar. “I think there are relationships here that have been damaged. The whole thing is unbelievable.”

The controversy comes at a hectic time for Tanner’s office. For the past few months, prosecutors have been feverishly preparing for the notorious Xbox murder trials, which were moved to St. Augustine from Deltona after intense pre-trial publicity. In the case, four men are accused of beating six young people to death with baseball bats. Tanner, who hadn’t prosecuted a case for almost two years, decided to personally lead the prosecution team. Tanner said he chose to take the lead role to increase public confidence in the prosecution, but his decision also seems timed to revive his reputation — particularly in light of the triple conviction Tanner won in the case last week. But as much national attention as the trial has garnered, local focus remains on the Lisa Tanner video. Recently, Tanner took a lunch break from the Xbox murder trial to hold a press conference to address the Police Benevolent Associations’ newspaper and radio advertising campaign against him.

“The closest thing I can analogize it to is a rapist or child molester,” Tanner told reporters. “They always want to blame the victim, and that’s because quite often that’s their only defense. These ads they are running are misleading and untruthful.” Tanner added that he does not believe he has engaged in a conflict of interest. “I have not at any time stepped into the courtroom and handled anything involving my daughter Lisa.”

Lisa’s reaction took a less metaphoric slant than her father’s about the local sheriffs. “I think they are all a bunch of fucking cocksuckers,” says Lisa. “Can you print that? I usually try to have more couth than this, but I can’t take it anymore. I’m losing my fucking mind.”

Public reaction remains mixed. St. Augustine business owner Norbert Tuseo, a member of the Lincolnville neighborhood crime watch, has worked with Tanner in the past and admires him. He watched the video online (a Google search for “Lisa Tanner jail video” turns up several viewable copies) and says, “I was not happy with it. I think the corrections officers need to protect themselves, but I’m opposed to brutality. That’s not the purpose of a county jail.”

Tuseo sees potential for conflict in Tanner’s role, however. “What he’s supposed to do is go after people in the system,” says Tuseo. “Unfortunately this happened to his daughter, but if that’s what it takes to bring it to the forefront then maybe other prisoners will not be abused.”

Dave Byron, spokesperson for the Volusia County Jail, would only say, “In a jail you have a lot of unhappy people, let’s be realistic. They don’t want to be there.” Asked specifically about the Lisa Tanner incident, he replied, “I’m not going there. We have to work with Mr. Tanner, and it’s important that we have a good relationship with him.”

On Nov. 9, 2005, Lisa was arrested a second time by Officer Nathaniel Juratovac, the same officer who arrested her on March 24. This time the charges included battery on a law enforcement officer, resisting with violence and obstruction of justice. According to police reports, Lisa tried to prevent Juratovac from arresting her friend, Michael McGuirk, who had an active felony warrant for violation of parole in Volusia County. Lisa physically tried to prevent McGuirk from being arrested and ended up in cuffs herself. According to the police report, while officers were waiting for a female officer to arrive to search Lisa, she begged them not to arrest her and offered information on crack houses in Flagler Beach in exchange.

The grand jury appeared to doubt the veracity of the police report. After State Attorney Hill showed the grand jury the video of Lisa Tanner’s prior arrest, jurors concluded that it caused her violent response to the second arrest. Chip Thullberry, Hill’s spokesperson, states “Because of the direction the investigation took, we thought it related to her arrest in November to show the video.”

The grand jury also found Officer Juratovac totally unreliable, implying that he’d fabricated charges. “He is simply not believable,” they wrote. “[W]e urge State Attorney John Tanner to refuse to use [Juratovac’s] testimony in any criminal prosecutions and to dismiss all cases based solely on his testimony.”

The jurors suggested Tanner “continue to vigorously investigate all allegations of abuse to insure the integrity of our corrections system.” He took this directive very much to heart. Shortly after the jail issues emerged, Corrections Director Dan Nagy was placed on administrative leave. (Nagy subsequently resigned.) Soon after that, Tanner sent a letter to private lawyers in the 7th Judicial Circuit soliciting complaints about the jail and Juratovac.

Meanwhile, all charges against Lisa Tanner were dropped. Michael Millea, who was arrested with Lisa the first time on lesser charges, did not have his charges dropped. He was also denied a public defender. Lisa was granted a public defender — an issue that generated more controversy since it was discovered that she is not indigent, but actually is the partial owner of a piece of property. Now law enforcement officers want her charged with perjury. “People have nothing better to do than do this?” Lisa asks. “They need to get a fucking life.”

Perhaps the irony lies in the fact that the controversy has compounded the damage for Lisa. Unable to escape the attention, she told Folio Weekly recently that she’s moving out of state. “I feel like I’m endangering my friends and family,” she says. “I just finished my bachelor’s degree at UCF with a 3.2 GPA — but no one wants to talk about that. I’m leaving because there’s no possible way I can get a job here. Who will hire me?”

Lisa doesn’t believe the scandal has impacted her father’s ability to work, and she points to the Xbox case as proof. “I don’t think this situation takes away from my dad.”

But she loses all defenses when asked what she wants to see happen. Her angry voice becomes childlike as she starts crying. “Basically, all I want is not to talk about this anymore.”