Bukowski and Me

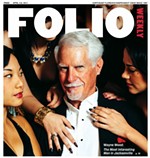

Claude Powell

In the early 1970s, Northeast Florida photographer Claude Powell lived in the St. Augustine neighborhood of Lincolnville, where he recorded in gritty and loving detail the lives of the people around him. His street scenes -- mostly men, mostly black -- recall Diane Arbus' portraiture, in which subjects, even strangers, let their guard down and invite the photographer in.

During the time Powell was shooting in Lincolnville and traveling periodically to Los Angeles, he became friends with famed poet Charles Bukowski and Jacksonville poet Alan Justiss. In this reminiscence, Justiss recalls this wild era, and his memories of both men, now deceased.

The bulk of this remembrance is about Claude Powell and Charles Bukowski, so I will begin in 1967. That year, I was a student at what was then called Florida Junior College, living in a $30-a-month apartment on the corner of Gary and Larue in San Marco.

It was a busy time for me, personally. In the first three months of that year, I completed my run as Action, one of the Jets in "West Side Story," at the San Marco Little Theatre; won the Haydon Burns Award for best three-act drama for my interracial play, "The Apple Cart" (Mayor Haydon Burns had hopes of cooling the city's race problems); and served as editor of the literary magazine Reason 67 at Florida Junior College. I was 24 and three times married.

As summer neared, my sister Stephanie would stop by my apartment on the weekends with skin of Copper-tone and surfboards on the rack. She introduced me to her surfer boyfriend and my future brother-in-law, Claude Powell. Like my sister, Claude was interested in my writing. Like my sister, I was interested in his photography.

Claude had just graduated from Robert E. Lee High School on the Westside, and at that time was taking pictures of the homeless people and winos in Hemming Plaza, showing them mostly to friends. His ability to win the participation of his photographic subjects was due in large part to great personal magnetism. I recall once driving with him from Keystone Heights to St. Augustine when, on a whim, he pulled off the road near Hastings. He grabbed his camera bag and disappeared into a field. The next thing I knew, he was sitting above a disk plow, being pulled along between the rows and snapping pictures of migrant workers.

Claude was also able to use his camera in such a way that girls would gladly remove their clothes for him. I had a number of girlfriends who posed naked for photographs. But the pictures, like his other portraits, were revealing without being exploitative.

I was eager to get out of Jacksonville, and in June I answered an ad to drive a 1967 Corvair convertible from Norfolk, Va., to L.A. I was given $150, the keys and seven days to make it there.

I didn't need seven days. I spent the first night in Atlanta, the second in Dallas. I read the front page of the July 22 Dallas Morning News in a half-lit bar that second night and saw that Carl Sandburg had died. I woke with a frantic hangover and drove for 36 hours straight.

My plan was to get to L.A. early and find my way around. I found a place on La Brea and Hollywood Boulevard, and four months later got my bride back into bed. We moved first to Silverlake, and later to Pasadena, where we took the upper half of a house overlooked by mountains. My sister and Claude moved out to California two years later, and stayed with us and found work -- she in a short dress at an insurance company, he in protective leather gloves from his job at Pacific Pipe and Clay, where I then worked. I got Claude his job there, working in the brick and pipe yard kilns. Claude kept his Nikon in a wall locker and took photos during his lunch breaks.

By 1970, I was no longer married. Neither was Claude. We were both having some success in our fields. His photography appeared in Rolling Stone, my poems were published in the Georgetown University Courier.

The hippie-'60s had ushered poetry readings back into the cellars, and I made the scene for a while. Claude attended these open readings. He was now shooting with a Pentax 35mm. During one of his forays, he met famed poet Charles Bukowski.

I moved back South that year and lost touch with Claude for a while. But he came through Gainesville in 1971, when I was working in the University of Florida English department, and started looking for me. He asked around the bars and bookshops before tracking me down at Anthony's Bar & Grill. "Christ, Alan," Claude joked, "you're better known than Bukowski around here."

I came late to Bukowski. I was too busy writing my own mistakes. But he and I were kindred spirits, and we met once -- memorably. My single interaction with Bukowski was later featured in several poems and some of his prose, as well as a section of The Buk Book: Musings on Charles Bukowski, a seminal biographical work by performance poet Jim Christy (see sidebar).

Claude Powell met Bukowski much earlier, and photographed the poet in his Hollywood home. The photos, several of which accompanied Christy's book, feature openly sexual interactions between Bukowski and a former Flagler College student who ran with us at the time.

When Claude moved back to Florida, he lived in St. Augustine with Leslie Harrill, the owner of Ankle, Thigh & Upper Half, a small boutique on Charlotte Street. Claude and Leslie bought a two-story, wood-frame, broken-down house in Lincolnville. Claude said he felt safer there than anywhere, despite being the only white people for blocks around. He had a job driving one of the two garbage trucks that serviced the city of St. Augustine, and one morning I went along on his route. I still feel my senses perk up thinking of the tilt of the dumpster from Bettes Fruit Stand. Citrus fruit and juice rained on the windshield while the rotten pulp dumped into the open mouth of the truck. Claude kept his camera bag on the front seat, and I was with him when he took some shots on the fly -- morning photos of mist rising from the landfill, of a cracked china doll torso.

We spent our weekends drinking and smoking. I was a pretty boy and women were always a problem. Claude and his friends would crash with me on the 10-acre island near Keystone Heights where I lived, or I would stay in Lincolnville. But Claude didn't stick around long before heading back to Hollywood. I returned, too, in 1973, hitchhiking with the two women who shared my bed at the time. We crashed one night in Dallas, and another in Tucson, at the home of a good source of Mexican brown H. We hit Hollywood, then San Francisco, where Linda fell for a drummer. Vicki and I returned to Hollywood, and I found work for a while.

Locating Claude would have been pure happenstance, and it never happened. Instead, I spent the nights writing and drinking, and when I ran out of money, I collected my guitar, Royal Companion typewriter and a pint bottle of Southern Comfort. Vicki and I headed to the Greyhound station in Hollywood, planning a return to Tucson. But in the alcove of the Hollywood Bus Depot, I opened my guitar case and started to play.

I kept my head down and didn't look up until I saw two five-dollar bills fall into the case. I stopped mid-note and looked up. It was a suit-and-tie who asked about my songs. He was part of the Rolling Stone masthead. He was headed back to San Francisco and had a fear of flying. He said he liked my songs.

Wilbur wouldn't hear of us returning to Tucson just to find a place to stay. He said Rolling Stone had rented property and could put us up in the Hollywood area. I said "OK" as he handed me a fifty and went to call us a cab. We gathered our belongings, and Wilbur took us up to the Los Feliz area, where Western Avenue ended. While Vicki and I unloaded our bags, Wilbur went to Ralph's, shopping. He came back with bags of foods and bottles of better wines. Before leaving, Wilbur said he'd be back in two weeks for some songs.

I had no idea what I'd gotten myself into in exchange for free rent and a swimming pool. But when he came back in two weeks, I obliged him. I sang a bottle's worth of songs before admitting that I just made them up as I went along, and couldn't remember of the words. It blew his mind all the same. Wilbur shot down into Hollywood the next morning and picked up a tape recorder and many blank tape spools.

Vicki required more than wine, though, and there was free junk in Tucson. Wilbur gave her some money and a ticket to our original destination. After he dropped her off, he came back for the weekend. When he left again, he took some recordings of my songs with him. The cash still came.

Wilbur called one day later that month, asked me to come up to his place. He had some people who'd heard my songs and wanted to meet me. I made it there but stayed too drunk for anyone. Before leaving town, I got over to City Lights Bookstore and saw the just-printed copies of Bukowski's Erections, Ejaculations, Exhibitions and General Tales of Ordinary Madness, which City Lights had published just days before. It had a Claude Powell photo of Bukowski on the cover (the photo credit appeared only in the first edition). I bought a copy, along with the small chapbook by Bukowski's girlfriend Linda King. The books picked me up all day.

I met an older woman around this time. She liked to drink and to buy me the good things that she kept at her place. Stella had a good 20 years and pounds on me. She'd been married to a Beverly Hills medical diagnostician, but now owned a 50-piece porcelain serving set of china -- each piece unwashed and stacked around the sink. Stella's place looked primordial, with mold composting in all known colors. I washed them, but she would fill them again with take-out Greek food from the restaurant across the street where we had first met.

We stayed together often. At some point photography came up and I showed her the book photo that Claude had taken of Bukowski. Stella was shocked by how Bukowski looked. Fuck the face, I told her: Read the book.

She did. A few years later, she would herself be a character in Bukowski's poems.

I was at my place one night and had just finished reading Taxi Dancing by Linda King. Inspired, I called her listed telephone number. Book talk brought an invitation to visit, and on the way over, I had the cab stop for wine and beer.

Linda lived in the Silverlake district on Michaeltorena, near the first house I'd rented in California. Like all the houses on the hillsides, this one had a long flight of steps to the front porch. She came to the door and took my uncalloused hand. "Well," Linda told me, "you are my first admirer."

I let her know how I felt about her writing, and she asked to read my palm. She took her time and told me that I would have a long, long life. It just drove her crazy for some reason. She kept saying loudly, "Look how long it is. Can you see it?" I learned later that Buk was hiding and overhearing us.

As an afterthought, I spoke Bukowski's name, asking her if he had "a long one." She started laughing at the sight of Bukowski coming out of the bathroom into the hallway. We hit it off, and the wine and beer quickly disappeared. We stood no taller than one another. He did a White Port shuffle and began punching into the air, recounting the go-around he had given Ernest Hemingway in a ring in downtown L.A. I was calling him "Pop," and he got pissed each time.

"Yeah," I said, "show me how you did it back then."

We were standing before French doors, and he punched his fist through one pane. I laughed and said, "What a joke. If it had been me there in the ring, I could have taken him, just like this." Holding a bottle in my right hand, I sent my left fist eight times into another pane. I was beyond feeling it. Linda began screaming.

Bukowski's blood and mine had made the floor quite slippery, but somehow we made it to the front door before I was pushed out across the porch, backed up by a chorus of screaming. The front door slammed. I fell in the bushes, face down in the dry dirt.

I lay there a good long while, listening to howls that named many hurtful names and places to go. I lay there silent, a bloody mess, until I heard voices and laughter. It made sense to me that the laughter was coming from Claude. He'd been to this place before. I waited for him to draw near the top last step, and then I hollered out, "CW. I'm over here!" (I used to call him CW, short for Claude William, his middle name.) I raised my bleeding, stained hand. Then I heard, "Hey, here's one of them." I was pulled upright, cuffed and shuffled down the long flight of brick steps. The police brought Bukowski along

for the ride, too.

I'd lost a lot of blood by that point, and it made me a bit lightheaded. I joked with Bukowski as we were driven to the drunk tank by L.A.'s finest. "So, is this how poets act?" I asked him. He told me to shut up, and I laughed.

We were booked minutes apart. I found a dry place on the tile floor, and he took a spot on the wall across from me, 20 feet away. He asked for a smoke, so I slid him a pack. He felt that I should join him, and I knew I should, but I was near dead to the world without sleep. I couldn't stand.

Bukowski got out after a number of calls. I listened to him plead with Linda and, near tears, John Martin, the publisher of Black Sparrow, to come throw his bail. John lived miles away, but I later learned he called Linda and wired her the money.

I never saw Bukowski again.

Bukowski was long gone when I got out the next day. I took the western bus to Vermont, north to Los Feliz. Got into my A.C.-cold, curtain-dark apartment and shut the door.

A good 36 hours later, I came awake and took a shower. Then I stood before a full-length mirror and for the first time got a look at my arm. It did not look good. The colors below my pale skin matched the molds I had seen in Stella's kitchen. I called my father, who recognized it as gangrene. He had seen it in the South Pacific and that other war.

I called Stella, and she knew a good hospital. We got in, almost without stopping. The doctor stabbed me twice in the cheeks and said in another six hours, I would have lost my hand* (see sidebar).

Less than a week later, I left a note on the table with no forwarding address. Stella and I had had a drunk last night together, and I was heading back to Florida for the winter.

By the time I got back home, Claude was in St. Augustine. When I got over his way one day, he welcomed me with words wide open raising his hand. "Alan, you made the L.A. Free Press!" I read what Bukowski took time to say about the night we met. He wrote an article about our evening together. It was a two-part piece in the Free Press, in which he referred to me as Billy Thong. He used the same moniker in a later poem, titled "the new woman," in which he recounts learning that I was Stella's ex:

You mean you really lived

with Billy Thong?

listen, I went to jail one

night with that filthy swine.

a matter of busted door glass

at my x-girl friend's place.

I busted out eight panes,

he got one.

they put us in the same

tank.

he was so disgusting the others

in the same tank

wanted to kill him.

they should have.

I saved his ass by

explaining him

away.

Oh fuck Billy Thong,

she says, and let's get on

with us.

Bukowski referenced me and Stella in two other poems, "we both know him" and "culture." All three poems appeared in the book Dangling in the Tournefortia.

I heard from Linda King a few years ago. She told me that Bukowski had a hand in helping her write her book. He was good, even when it came to writing in a woman's voice.

Of course, I knew he was good. When he wrote about our night together, he claimed I'd put my fist through one pane of glass while he put his through eight. It was his way of getting my attention, letting him know that he was thinking about me -- not as Alan, but as Billy Thong.

Claude lost his father when he was very young; he was killed in some sort of accident. Claude himself was injured as a child when he was hit by a car while riding his bike. He was dragged along the street some distance until the flesh from his outer right thigh was gone and he lay still. The driver was never found.

In later years, Claude would describe the great joy he got from his son, Forest. Claude, who worked for a time as a boat captain delivering crafts to Africa and South America (he even worked for Donald Trump), admitted that before his son was born, he occasionally felt adrift. He described Forest as the rudder in his life.

It's Claude who should be telling this story. It's his pictures that give that era its indelible stamp, his photographic memories that evoke and celebrate those wild years. But Claude died in New York on Nov. 12, 1999. He left behind hundreds of negatives, pictures that have never been seen. They await development, a darkroom birth, to be properly exposed. I'm pleased to hear that his son has shown an interest in his late father's work, a desire to put his photographs in order and bring his memory to life.

Every photo, in its way, offers a bit of history. We must move through them slowly, one frame at a time.