Beat By The System: An Abused Woman's Story

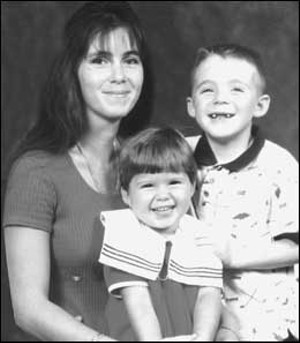

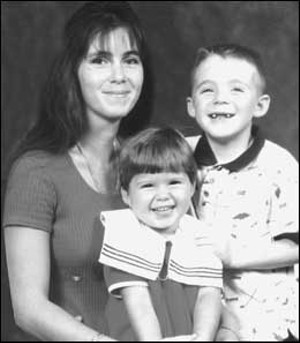

Larae Rebecca Geiger and her children

An exceptionally tiny baby came into the world on Oct. 13, 1975, in Gainesville. Larae Rebecca Geiger was a small child with boundless energy and big trusting brown eyes. Larae’s was not an easy childhood or one that promised great things. Neither did it suggest she’d be brought down in a rain of bullets before her 30th birthday. The drama of real life is rarely that rich in portent.

Larae’s mom worked nights and slept during the day. Her dad, injured on his construction job when a crane fell on him, collected disability and boarded horses. According to interviews of Larae by psychologists, both her parents had drinking problems, and theirs was a volatile relationship. Though they loved Larae and her brother, 11 years her senior, they had a difficult time showing it. They believed in hard work and had little use for formal education. Larae dropped out of school after fifth grade. Her mother planned to home-school her, but she’d had little formal education herself, and it never happened.

Larae’s brother joined the Army when she was 7. When she was 12, doctors determined she was legally blind. When she was 15, she found a note from her mother lying on her bed. “I will always love you,” it read. Her mother was gone.

In the months that followed, Larae and her father met 20-year-old Paul Huff at a horse show. He started coming around, expressing an interest in horses. Larae was innocent, vulnerable and starved for affection. Huff easily won her trust. Psychological evaluations of Larae show that several months after they met, Huff moved in with Larae and her father and began having sex with the 15-year-old. Not long after that, he began to beat her. Friends and relatives began noticing cuts and bruises on Larae’s body. According to Larae, Huff already had a drug and alcohol problem. Despite this, the pair married in 1993. Larae was 17.

For several years, the couple lived with Larae’s father before moving to a series of homes around Clay County. They finally settled in a trailer in Keystone Heights in Clay County. According to discovery documents submitted during Larae’s 2003 sentencing hearing by family, friends and even casual acquaintances, Huff exerted total control over Larae’s life, choosing her friends, telling her what to wear, and what to eat and drink. The statements contained vivid accounts of battering and severe psychological abuse. One witness saw Huff stuff a rag down his wife’s throat when she didn’t clean the floor to his liking. Others saw him bang her head into a wall until the Sheetrock broke, and drag her by her hair from a room. Some of Huff’s friends tried to “pull him off” when he was beating Larae, or “talk him down” when he had already beaten her or was getting ready to do so.

Several witnesses testified to blackened eyes, split lips and large bruises, which covered the places her clothes did not hide. On one occasion, Larae Huff was found by a state trooper wandering in Baldwin in a dissociative state, without a clue where she was or how she got there. Another time, according to hospital records, Huff found her lying in the middle of the living room with no memory of what had happened or why she was on the floor.

Physicians’ records indicate Larae was diagnosed in September 2001 with adjustment disorder, depression and anxiety, compounded by what doctors gently labeled “marital discord.” She was placed on antidepressants. A short time later, her husband flushed them down the toilet.

During this period, Larae later told psychologists, Huff changed jobs frequently, sometimes with significant periods of joblessness. Unemployment infuriated him, and he blamed others -– particularly Larae — for his inability to maintain a stable position. The couple was living in a nicely appointed doublewide trailer in a remote, densely wooded area. To supplement his income, Huff’s Keystone Heights neighbors contend he turned to the drug trade; cars came and went from the trailer at all hours of the day and night.

Larae, who had always wanted children, naïvely thought the beatings would stop when they had kids of their own. But the abuse continued when Larae became pregnant with her son Dolan in the mid-’90s. Her second pregnancy ended in a miscarriage, then she had a daughter, Lascena.

Despite her troubled marriage, Larae heaped love on her children and maintained her own strong belief in God and the existence of goodness in the world. For a while, she talked her husband into attending church, and the beatings became less frequent, but the calm didn’t last.

According to psychologists’ interviews with Larae, Huff began to blame her for his every inadequacy, calling her a “stupid, no good, retarded idiot.” He told her she couldn’t survive on her own, but threatened that if she tried to leave, he’d kill her. She had no doubt he meant it.

According to the Huffs’ friends and neighbors, around June 25, 2003, the abuse seemed to escalate. Neighbors said one day Paul Huff chased Larae in the yard with a bulldozer and tried to run her down. The beatings were as regular as clockwork. When neighbors saw her, she was perpetually bruised and cut.

The children witnessed much of this. A psychological assessment found that during this time, the kids’ “relationship with Mr. Huff was getting more problematic. They were becoming more afraid of him. [Larae’s] daughter clung to her and wouldn’t speak to other kids or listen to the teacher.”

In early July, Huff was beating Larae when he grabbed a shotgun from the closet. He stuck the barrel in her mouth and said he was going to kill her. Larae Huff recalled in three psychological assessments that she wanted to die. “Please go ahead and blow my head off,” she begged.

“You’re not worth going to prison for,” Huff shouted.

Larae ran from the room and found her 10-year-old son sitting outside the bedroom door. “I felt so bad for my son.”

After the shotgun incident, things got worse. Each day before Huff left for work, he promised Larae he’d kill her when he came home. Each day she waited, torn between terror and exhaustion, for him to return. The morning of July 9, Huff told her to say goodbye to everybody she knew, including the kids, because it was her last day on earth.

Richard and Lee Hopson, an older couple that befriended the Huffs and for a while employed Paul Huff, said Larae called on the morning of July 9. She wanted to come over, but the Hopsons had relatives in town, and Lee told her, “It’s not a good day to come over.”

Larae began to weep. “Nobody has time to talk with me,” she cried.

Lee stayed on the phone with Larae for an hour and a half, while Larae poured her heart out. She finally admitted, “I can’t take it anymore, Mrs. Hopson.”

Paul Huff called Larae around 2 p.m. that day to remind his wife of his plans. “I’ll deal with you when I get home,” he threatened.

“You know what?” she replied. “I’m going to blow my brains out.”

According to Richard Hopson, Huff called him and asked him to check on Larae. He said she was “upset, and threatening to kill herself.” Hopson figured that given Larae’s uncharacteristic boldness with her husband on the phone, Huff probably wanted to make sure Larae didn’t shoot him when he got home.

At approximately 4:30 p.m., Larae packed backpacks for her children and sent them to a neighbor’s trailer down the road. Her 10-year-old son said his momma was crying. She told him, “I love you both so much — don’t ever forget it.”

By the time Richard and Lee Hopson arrived, Paul Huff’s car was parked at the east end of Lovebird Court, the dirt road that led to the trailer. He told Richard that he’d heard gunshots and asked him to check it out. As Hopson got closer to the house, he saw the children coming down the road. “Mama has a gun, and she doesn’t want anyone over there,” Larae’s son told Hopson.

Hopson sent the children to a neighbor’s house, and continued on to Larae’s trailer. The metal gate across the driveway was closed, so he opened it and walked around to the back stoop. The place was quiet. Larae came out, dragging a 12-gauge pump shotgun by the barrel. She looked thinner than Richard Hopson had ever seen her, and weariness surrounded her like a shroud.

“I don’t want you here, Richard,” she said sadly. “I don’t want anybody here. I just want to be left alone.” She walked back inside.

Hopson looped around to the front porch and stood there as Larae emerged carrying the shotgun with both hands, barrel pointed in the air. “Just put the gun in the house and we’ll talk,” he begged.

“Please just leave,” she directed. “Close the gate and get my kids. Tell them I love them.”

At approximately 5:42, the Clay County Sheriff’s Office received a complaint of a “family disturbance” at the Huffs’ address. Officer Jeffrey John Brokaw was dispatched. Brokaw parked his car down the road, out of sight of Larae’s trailer.

Richard Hopson began walking to the neighbors’ trailer where Lee was waiting with the children, when he saw Paul Huff on the phone and a “real big” officer sitting in his patrol car, one foot out on the dirt. Richard walked up to the car and was standing beside it when a shotgun blast rang out. “That officer hit the dirt,” Hopson later recalled, though he and Huff remained standing.

While lying on the ground, the officer frantically reached one hand into his patrol car and pulled the radio to him. Richard Hopson said the officer shouted that he’d been shot at and needed help.

“I was just standin’ up beside the car lookin’ down at him, wonderin’ why he was laying there — on the ground,” Hopson recalls in a slow Southern drawl. “Me and Paul didn’t head for cover. We knew she wasn’t shootin’ at anybody. But I was afraid she’d shot herself.”

More shotgun blasts rang out in the distance, Hopson recalls, and Officer Brokaw seemed “real scared, and began shouting in the radio.”

After that, he adds, “the situation got out of hand real quick.”

The woods were soon filled with officers, guns and vehicles of every description. The Clay County Sheriff’s Office set up a command post at the intersection where Lovebird Court meets Westbrook Drive, blocking access in or out. They also set up a hostage negotiation unit just north of the command post on Westbrook. Meanwhile 19-year Sheriff’s Office veteran Sgt. Paul Theus, the dispatch supervisor, reached Larae by phone.

Theus had no prior negotiating experience, but he immediately developed a rapport with the young woman. According to transcripts of the conversation between the two, Theus began asking questions about Larae’s situation.

“I got two beautiful children, and I love them to death,” Larae told him. “But I have been accused for doing stuff for so long and — and wrong for so long that I — it’s drove me over the edge.”

Theus talked about her children. “Just don’t do any more shooting,” he said.

“I’m hurting,” she answered.

Sgt. Eddie Eisenhauer arrived on the scene and contacted dispatch. He wanted Theus to turn the conversation over to him. “I didn’t feel comfortable relaying her to another police officer,” Theus said in his deposition. “I think she was wanting to tell somebody about her problems but wasn’t — you know, didn’t trust the police.”

Theus said he believed the young woman just wanted to be left alone to work out her problems. From the transcripts, it appears Larae Huff’s emotions changed from moment to moment. She went from sorrowful to angry, threatening to apologetic. “I don’t want you to hurt yourself, and I don’t want you to hurt nobody else,” said Theus.

“I don’t want to shoot anymore either, but you better tell them to back off because they’re gonna get their head blown off if they don’t.”

She immediately began to apologize. “I’m sorry. I’m really sorry … and I made sure I — I made sure I looked, and I didn’t shoot toward somebody else.”

The call continued for about 10 minutes, at which point it appears the Sheriff’s Office broke in on the communications. Negotiator Mack Wheeler tried first to speak with Larae, but he called her by the wrong name and she hung up on him. Negotiator Renee Scucci tried next, and spoke briefly with the young woman a number of times. Scucci said Larae intermittently hung up the phone and discharged her shotgun, and that her manner was “up and down.” At one point she was “giddy,” Scucci said. When asked in depositions, she said she didn’t think Larae’s statements and thoughts were rational. Most of the calls were on a cell phone, and none were recorded.

Negotiator Lt. Ronnie Gann, who was assisting Scucci, agreed Larae’s behavior was “bizarre.” But negotiator Lt. Pat Murphy, who relayed information from the negotiation unit to the command post trailer just up the street, had a different take on Larae Huff’s behavior. Officer Murphy never spoke to Larae or heard her voice, just listened to the negotiators, but he reported a very different tone to the conversations. He told the command staff that Huff did not appear to suffer from any anxiety, depression or agitation. “It is my impression that she felt like she had the whole situation in control,” he said in deposition.

Chief negotiator Lt. Dan Smith, who was monitoring the situation in the command vehicle, said Officer Murphy told the command staff that Huff was saying threatening things like, “I’m going to hurt you. I’m going to kill you.”

Officer Murphy’s interpretation was not the only one that suggested confusion at the scene. At the time the standoff began, Clay County SWAT team members were just returning home from a training exercise in St. Augustine. The message that most received was that an officer had been fired upon. SWAT members rushed to the scene in full “tiger camouflage,” with flak jackets and face paint.

“It was pretty scary,” recalls Richard Hopson, who believes their arrival ratcheted up intensity. “They rolled in, all hopped up from a day of practicing. They were all painted up, with all kinds of weapons. They were ready to move in.”

They were also under new leadership. A few weeks before the raid, Sheriff Scott Lancaster had removed SWAT leader Joel Hodges. Sheriff’s Office records show no reason for the move; under Hodges’ direction, the SWAT team had always had “successful resolutions” to calls. But the Huff incident was the first call without Hodges, and things quickly began to fall apart. According to SWAT directives, the first task of any job is to “secure the perimeter.” This includes surrounding the area, cutting off escape routes and, most fundamentally, disabling all vehicles. Sheriff Lancaster told a number of Sheriff’s Office personnel, who wished to remain anonymous, that problems arose that day because the SWAT team never secured the perimeter. For instance, although Larae Huff’s pickup truck should have been disabled, or at least monitored, it remained unguarded behind the trailer.

Larae Huff remembers only bits and pieces of what happened that day. According to psychologists’ interviews, she recalls that she drank several beers and smoked some of her husband’s marijuana to get the courage to shoot herself. But when the Sheriff’s Office kept calling, and when she heard officers moving around her property, she decided to go somewhere quiet. The only vehicle around was the Huffs’ 1989 Ford truck. It had a bad motor and wouldn’t go above 35 mph. Larae only used it to take the kids down to the bus stop at the end of the road.

By now, the SWAT team had taken over for sheriff’s deputies. According to officers’ depositions, they moved through the dense forest attempting to get in position around the trailer, located at the top of a dirt driveway that led up from Lovebird Court like the upper arm of an “L.” SWAT perimeter team leader Officer Steve Mills and Officer David Barnes were south of the home, at the joint of the “L,” when Larae went down to open the gate.

SWAT Sniper Albert Lundin made his way around the woods on the west side of the driveway, then took up a post near the gate. According to Lundin’s deposition, Larae Huff walked down the driveway with the shotgun over her arm and opened the gate. From about 50 yards away, he recalled, SWAT Officer Steve Mills began “yelling” at her, “and she’s not yelling back at him.”

Lundin recalled that Officer Mills told Larae to lower her weapon. She did, then turned and walked back toward the trailer.

Mills in deposition disagreed. He said she had leveled her gun at him, even though she “couldn’t tell where I was coming from,” because he had taken cover behind a tree. He said she was calling him names, “blah, blah, blah,” and “calling him out.” “I felt I was behind good enough cover that if she fired I wouldn’t have been hit.” Seconds later, SWAT members heard a vehicle start up.

“She’s gone mobile,” was the radio cry. “She’s gone mobile.”

The consensus later was that all hell broke loose at this point, but there were conflicting stories about just how it broke.

According to police logs, at approximately 8:12 p.m., officers heard a truck engine fire up. Evening shadows had begun to descend on Keystone Heights, and in about four minutes an intense rainstorm would hit. Larae began driving the truck down the driveway.

SWAT Officer Mills, who stood with Officer Barnes at the joint of the “L,” later recalled she was “coming at us pretty quick … about 35 miles per hour.” When he saw the vehicle, he readied his sniper rifle. “Permission to take out the truck,” he shouted into his headgear. Investigators’ timelines and some officers’ depositions suggest he asked permission while he fired. His first shot seemed to blow both front tires after Larae passed through the gate.

Mills told investigators later that he was behind a tree when Larae saw him and aimed her shotgun out the driver’s-side window. He claimed she fired directly at him. “That’s when I felt, you know, threatened.” Mills stopped firing at the truck’s tires and took aim directly at Larae. “I shot three rounds at [her] — through the door.”

Mills conceded Larae’s ability to aim and fire while driving was unusual. “After it was over, I was very impressed how she could drive and shoot and everything at the same time.”

Officer Barnes offered a similar version of events. He attested that Larae “pointed the shotgun out the window as she’s driving and fired — fired the shotgun to where she, I guess, assumed that Sergeant Mills was.”

Deputy Brokaw, having been relieved of his post, was walking through the trees on the south side of Lovebird Court when he heard “rapid” gunshots. He ran “up into the tree line … in fear for my life.” Though he faced the passenger side of the truck, which had a tinted window that was closed, Brokaw told investigators, “I observed the barrel pointed at me.” In response, he “aimed at her” and fired four rounds.

Sgt. Eddie Eisenhauer, a first-line operation supervisor, kneeled between his Ford Explorer and a Chevy Suburban parked on the north side of Lovebird Court. Eisenhauer later said he saw Larae firing out the driver’s-side window as she came down the road. Though other officers said they could only see a silhouette in the truck, Eisenhauer said he could see Larae’s face clearly. He recalled she was looking directly at him, with her left hand on the steering wheel while she used her right hand to fire the shotgun out the driver’s-side window, all the time accelerating straight toward him at an estimated speed of 50 mph.

Richard Hopson, who was standing in front of the command post, just a few car lengths from Eisenhauer, offered a less menacing appraisal. “The old truck wouldn’t half run, and they’d shot the tires out,” he described. “The road had big old humps, and the truck was bumping up and down. It might have gotten up to 10 miles an hour. It’s luck she could even hold it on the road with two hands.”

Hopson says Larae never fired her gun while driving. But when she turned off Lovebird Court into a clearing, Eisenhauer began shooting. He continued to fire until he emptied his 16-round Glock. Hopson recalls one officer shouting at Eisenhauer to stop shooting because there were SWAT officers in the woods where he was firing. Lee Hopson dropped to her knees and began praying.

As Eisenhauer finished shooting, SWAT member Christopher Coldiron rose up from behind the front corner of the command post vehicle and fired two bursts, or six rounds, from his MP-5 submachine gun into Larae’s vehicle. The truck veered out of the clearing and headed into the trees. Then SWAT Officer Kenny Brown, freshly returned from duty in Afghanistan, stood or kneeled, according to the many accounts, and braced for Larae.

Larae Huff had already been hit, probably by Coldiron. The terrain was rough with multiple trees and stumps. The truck tires had been blown out and considerable damage had been done to the already malfunctioning motor. Despite all these factors, Brown said Larae was moving “fast,” pointing a gun at him, trying to shoot him and attempting to run him over. He said as the truck “passed” him, he began firing. He fired 14 times with his MP-5. The truck crashed into a stand of trees, and became wedged between two trunks.

Richard and Lee Hopson ran for the truck, but were restrained by officers.

“My God, we’ve killed a kid,” Hopson heard one officer yell.

Larae Huff was seriously wounded, but still very much alive. She’d been shot in her left calf, right knee and upper left leg. (That bullet lodged in her pelvic area, and is still there today.)

Descriptions of the crash site were as varied as versions of the shootout, but a number of officers and paramedics said that as Larae Huff was being removed from the vehicle, she was crying and apologizing, and continued to do so until she was lifeflighted and sedated at the hospital. She said she didn’t blame the officers for shooting her, and that she would never have hurt them.

Less than two minutes passed from the time the truck “went mobile” until it crashed. In that time, the vehicle was shot at 44 times, and Larae had been hit three times. Bloody and weeping, she was removed from the truck. She lay handcuffed, her face on the ground. Then the sky opened up and it began to pour.

An investigation of the incident by the Florida Department of Law Enforcement began within hours of the shootout. It included a detailed map of spent shells and evidence collected during a shoulder-to-shoulder walkdown of the scene. In some cases, the evidence the FDLE gathered conflicted with sworn accounts from officers at the scene.

For instance, FDLE investigators found spent shotgun shells only in the immediate area around the trailer’s front porch — “on top of it, around it, on the ground underneath it, underneath the steps” — indicating that the only shots Larae fired were shot from the area around her porch. No shotgun shells were found in the truck, on the driveway or anywhere else on the property.

FDLE investigators also discovered that after firing her initial shots, Larae Huff loaded 16-gauge shells in the 12-gauge pump shotgun, rendering it useless. According to FDLE agent David Warniment, a 28-year firearms examiner, “16-gauge shot shell cannot be fired in a 12-gauge shotgun.” The shell, when chambered, would essentially slide down the barrel and possibly jam. If a 12-gauge shell was subsequently chambered and fired, experts said, the gun would explode.

The gun was a pump-type shotgun. Experts with FDLE said it would take a normal-sized person two hands to pump a shell into a firing position, something that was difficult for the legally blind, 100-pound Larae Huff anyway, but particularly difficult to accomplish while driving.

Some officers who were on the scene now say they believe it was a “miracle” that Larae Huff survived and that no officers were wounded by friendly fire. “Bullets were going everywhere,” said one. “It was a f*cking goatrope.”

Interviews with officers were conducted the night of July 9 and in the early morning of July 10. All of the officers who shot at Larae Huff said they did so because she shot at them first. Officers who witnessed the shooting agreed, but some later changed their stories, saying their accounts had been “hearsay” from other officers. All of the officers said they knew the difference between the sound of an old shotgun and that of the submachine guns and sniper rifles used by SWAT team members, which had silencers attached, or the Glocks used by county deputies.

Despite the inconsistency between officers’ versions of events and the evidence collected by FDLE, Larae Huff was charged with three counts of aggravated assault on a law enforcement officer. Two of these charges were based on statements by Officer Mills and Deputy Brokaw, who accused Larae of pointing a gun at them. The third charge stemmed from Officer Kenny Brown’s statement that she aimed her truck at him. For allegedly firing her weapon at Mills and Brokaw, Larae was charged with two counts of attempted first-degree murder.

Larae’s case was assigned to Public Defender Kelly Pappa. Armed with proof from the FDLE investigation that Larae’s shotgun was never fired after she left her house, Pappa shot holes in officers’ versions of events. But the fact remained that Larae Huff had discharged a weapon with officers in the area, a very serious offense.

Pappa had Larae Huff examined by Dr. Lenore E. Walker, a forensic and clinical psychologist from Ft. Lauderdale, and one of the foremost experts on the psychological impacts experienced by battered women. Walker determined that Larae Huff suffered from a type of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) known as battered-woman syndrome. The doctor said Larae developed a “learned helplessness from the battering relationship” that prevented her from leaving her husband. Walker said that the abuse she suffered caused her to fall into a dissociative state on July 9, as she had done on two previous occasions in 2001 and ’02.

Clay County Assistant State Attorney Shauna Wright had Larae examined by Dr. Wade Myers, an associate professor of forensic psychiatry at the University of Florida. Myers suggested that battered-woman syndrome was “a controversial legal concept,” one “that has to do with a self-defense justification” for violent crimes.

Myers did, however, believe that Larae’s “characterological makeup is consistent with dependent personality disorder.” He said that while Larae appeared to have developed some acute stress disorder/post-traumatic stress symptoms, he felt these were the result of being shot, not abused.

Myers added that to be considered legally insane at the time of the incident, “Mrs. Huff would need to have been profoundly psychotic, and to have held the extreme delusional belief that the law enforcement officers around her house were somehow not really officers, but were her husband disguised in other men’s bodies.”

A third expert, Orange Park-based forensic psychologist Dr. Harry Krop, said that although he thought Larae appeared “sane” at the time of the incident, he agreed with Dr. Walker’s opinion that Larae “developed a dissociative disorder associated with PTSD and battered-spouse syndrome resultant to her abusive relationship with Mr. Huff.” Krop said her “judgment was significantly compromised, as was her capacity to conform her conduct to the requirements of the law.” The doctor said given Huff’s personality profile, it was likely her only intention was to harm herself.

Because of the severity of the charges Larae faced, Pappa pressed for some kind of plea agreement. In exchange for a guilty plea, prosecutor Wright agreed to drop the two attempted murder charges.

During a July 28, 2004 sentencing hearing before Circuit Court Judge Frederic A. Buttner, Pappa presented letters from friends, neighbors and acquaintances about the abuse Larae suffered. Drs. Krop and Walker said Larae was not a danger to herself or others, and that with counseling, she could recover from her mental illness and lead a normal life. Krop said it was unlikely she’d receive the treatment she needed in prison.

Larae also testified at the hearing. She offered a heartfelt apology to the officers involved. She said she didn’t remember much about July 9, but, “I know when you came out there, you were trying to help me. You didn’t know what I have been through.” She also said she would have never hurt the officers.

Larae talked about the changes she had made since the incident. “I now know what it is like to have friends, to believe in myself. I know I’m not a loser, and I am smart,” she said. “I know I want to be there for my kids.”

Larae begged for forgiveness from the officers for scaring them. She begged to be allowed to raise her children. “I’m asking for mercy to the court, to not have to go back to jail.”

Initially, it appeared that Larae might get a break. During the first part of the sentencing hearing, Pappa says she was confident, given Larae’s mental illness, her client wouldn’t be given a jail sentence, but time served and probation. Prosecutor Shauna Wright apparently thought so, too. She told Pappa that if the judge gave Larae Huff only probation, she planned to seek financial restitution for all the man-hours that the Sheriff’s Office had expended.

But the second part of the hearing took a different turn. Although FDLE reports concluded that Larae did not shoot her weapon at anyone, Wright was torn between the conclusions of investigators and officers’ testimony. In the end, she decided to rely on the officers. She began her sentencing statement saying, “… law enforcement officers, SWAT team members and hostage negotiators were sent scrambling for their lives as an angry woman began spraying them with shotgun blasts from her driver’s-side window as she tried to run them down in her truck.”

The officers who testified at the hearing continued to insist that Larae had shot at them. All except Officer Kenny Brown thought she should be sentenced to at least seven years. Brown felt she had suffered enough.

Judge Buttner appeared torn. “Regardless of all other evidence, it is a felony to fire a weapon near an officer,” he said when asked about the case recently. He finally sentenced Larae to three years in prison, followed by 10 years’ probation.

For Richard Hopson, the sentence was just another unnecessary punishment. “The thing that hurt me the most is they could have put an end to this when she was in her yard,” he says. “They could have shot her with one of those rubber bullets and taken her down. Then the things that happened to her would never have happened.”

Larae was initially sent to the Lowell Correctional Institute in Ocala, which was close enough for Larae’s children and family to visit her. But during her first month, Larae was attacked by another inmate. Department of Corrections officials say that since she was in a fight, she was labeled a “dangerous” inmate and sent to the Homestead Correctional Facility in South Florida, which houses some of the most hardened criminals in the prison system.

Larae’s mother has had to take another job to support Larae’s two children, who have seen their mother only twice since she was moved to South Florida. Larae’s father is terminally ill and is unable to travel to see her. (Paul Huff divorced her several months after she was arrested. He was never charged with any domestic offense.) Kelly Pappa and Judge Buttner have both appealed to the Department of Corrections to move Larae back to Lowell, but both appeals have been ignored.

Since her arrest, Larae has been taking antidepressants and has undergone extensive psychological counseling. Friends and family say she is a different person: positive, brave and, while still very remorseful, ready to start a new life.

Public Defender Pappa believes things will be difficult for Larae when she is released in February 2006. But she wonders how she will meet the financial demands, and notes she will have to repay court costs and the accrued interest, as well as $45 a month for probation cost.

“She has nothing,” worries Pappa. “No belongings, no place to live, no job, no money, and two kids. Such a long probation with so many financial demands almost guarantees failure.” If Larae fails to pay, Pappa explains, she will have to return to prison to serve out her probation.

The Hopsons say Larae’s children, who stay with them regularly, are doing well and eagerly talk about the day their momma will come home. Larae still walks with a limp, and has a difficult time in prison, but she writes letters full of hope to her children, her family and Kelly Pappa. God meant for her to live that fateful day in Keystone, she says. And she is not going to disappoint him.