Less Than Zero: Terry Gilliam Slips On a Virtual Banana Peel

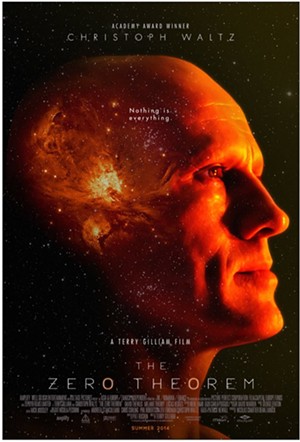

Terry Gilliam’s further slide down the stairs of filmic entropy is best summed up in an oft-repeated phrase by his latest film’s hypochondriac protagonist Qohen Leth, “Q” for short. “We are dying.” The editorial expression of Q’s imminent doom, as spoken by a bald-headed Christoph Waltz, takes on little meaning as the film’s wafer-thin dystopian story moves from point A to point B, if barely even that. Indeed, “We are dying, us, ourselves,” while watching this movie.

Q is a frail scientist working in stay-at-home conditions for an emblematic “management” (played by Matt Damon wearing a receding white hair piece) of a corporation known as Mancom. Q’s hyper stressful assignment involves “crunching entities” to prove whether or not human existence holds any meaning. Gilliam’s use of near 3D graphics to represent the computer program that Q uses to maneuver around bricks of formula into gigantic walls containing billions of other such bricks is about as visually compelling as counting cracks in a sidewalk.

Waltz’s hairless “worker-bee” character holds up in a converted church within a future version of London town where crossing busy streets filled with tiny eco-cars presents a dangerous proposition for pedestrians. Electronic advertising taunts the public at every step. “Everyone’s getting rich except you.” A giant billboard entreats the public to join the church of “Batman the Redeemer.” Think “1984” or “Starship Troopers.”

The offices for Mancom Corp. resemble a gaudy, smaller, steampunk version of the bureaucratic maze that Gilliam created for “Brazil,” via Michael Radford’s “1984.” Much like the NSA, Mancom sees and records all human activity. Day-Glo colors plastered on cheap set designs do little to distract from the film’s all too obvious budgetary limitations.

Management’s “Zero Theorem” posits what our collective subconscious already knows, that humanity’s precarious place in the universe is predicated on an unstable quantum chaos that can and will come crashing down at any moment, just as surly as it sprang into being. “Zero must equal 100%.” “All is for nothing.” It’s a thematic punch line that arrives like a big wet fart.

Some people — like American politicians and CEOs for its Industrial Military Complex, for example — have figured out how to make vast quantities of cash from instilling fear and causing chaos on nearly every spot of land on the planet. Q isn’t one of these people. He is afraid of everything, but he fears “nothing” most of all. Q has waited all of his life for a phone call informing him of his life’s calling. The closest he comes to receiving such a message occurs when he meets Bainsley (Melanie Thierry), a sexy little trollop sent by management to seduce him into wanting her before committing a clever act of bait and switch. Not one to be penetrated, Bainsley gives Q an all-body tantric sex suit with which he can sensuously interact with her through her website. Q’s liberation of spirit and body lies only in his imagination. The movie seems to posit that the end of humanity, as part and parcel to the intrinsic nature of our chaotic universe, can best be achieved by technologically produced illusions.

Management sends over its teenage son Bob (Lucas Hedges) to order pizzas and give youthful pep talks to the old man in case Bainsley’s naughty provocations aren’t enough to speed up Q’s formula solving. Management needs an answer, chop chop.

Newbie screenwriter Pat Rushin doesn’t know a plot point from a plot twist. Why Terry Gilliam chose to direct Rushin’s bogus script is a mystery more puzzling than the zero theorem itself. Perhaps the director of such cinematic milestones as “Brazil,” and “12 Monkeys” thought he could elevate “The Zero Theorem” into some kind of resolution to his “Orwellian” trilogy. There is no comparison between “Zero Theorem” and those other two far more convincing films. Gilliam completionists will need to see for themselves what we already know. The gifted genius that made “Time Bandits” and “The Fisher King” hasn’t made a good film since 1998 when he adapted Hunter S. Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” It might not be too soon to announce that “we” are finished.

Rated R. 107 mins. (C-) (One Star — out of five / no halves)

-30-