Lesbian Student Shut Out of Tradition

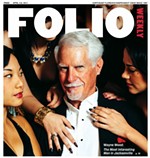

Courtesy Cady & Cady Studios © 2004

After she chose to wear a tuxedo instead of a drape, lesbian Kelli Davis had her photo banned from the yearbook.

Kelli Davis is an 18-year-old senior at Fleming Island High School. She’s an obedient daughter in an upper-middle class family. She’s intelligent (her senior grade point average is 4.0), responsible (she’s held a part-time job since she was 15) and attractive.

But to Kyle, a boy in several of her classes, she’s a "dumb f*cking dyke."

For the past two years, since Kelli came to grips with her sexuality, she has been forced to deal with the strange dichotomy between the person she knows herself to be and the identity foisted on her by others. Though her family has been unusually supportive of both her sexuality and her decision to live openly as a lesbian, the reception at her school has been less charitable. In fact, Kelli’s sexuality is the source of a dramatic rift, one that has dominated her senior year and which threatens to exclude her from that most fundamental record of high school life: the yearbook.

The source of the tension isn’t student intolerance. Though boys like Kyle have made Kelli’s life difficult and sometimes miserable, the real problem comes from higher up the high school food chain. The strongest opposition to Kelli Davis is led by Fleming Island High School Principal Sam Ward.

Fleming Island High School is a product of Clay County’s new affluence. Necessitated by the rapid suburban development on the west side of the St. Johns River, the high school was conceived in the late ’90s and opened in August 2003 to meet the needs of Fleming Island, one of the fastest-growing communities in Northeast Florida.

What began as just another high school quickly became a showplace. Clay County Superintendent David Owens approved pouring millions of extra dollars into the school, whose sprawling campus and innovative architecture more closely resemble a college campus than a public high school. Though other parts of the county desperately need new schools and repairs to existing ones, the expense was justified by making the school the new headquarters for School Board meetings.

More surprising than the cost of the new high school was the choice of the new principal, Sam Ward. A coach, teacher and principal at Orange Park High School for 18 years, Ward was not popular. Both parents and teachers found Ward’s uncompromising "my way or the highway" management style off-putting and rude. But he was and remains close friends with Superintendent Owens.

"The best thing that ever happened to Orange Park High School was Sam Ward’s leaving," one faculty member says. Indeed, some teachers who had an opportunity to transfer to the spiffy new Fleming Island school chose not to when they learned Ward would be in charge.

Reviews of his current performance are mixed. Several teachers criticize his lack of leadership, saying that in just two years, Ward has allowed FIHS to be taken over by a group of athletes who call themselves the "E Town Gang." Named for the upper middle class Eagle Harbor neighborhood where many of them live, the gang’s "colors" are pink polo shirts, worn with collars up. Parents and teachers say the E Towners terrorize and take money from kids who are weaker and hang in smaller numbers. Although the school has a zero tolerance policy toward alcohol and tobacco, teachers and students contend that E Town members routinely smoke and drink at school.

"Frankly, there are third graders in tougher schools who could beat up those kids," says one teacher. "But Ward turns his head and allows them to rule." More to the point, teachers say, punishment at FIHS depends on which child is committing the offense and how much money and prestige their parents have.

Despite problems at Fleming Island High, Kelli Davis excelled. "Kelli is a phenomenal student," says honors history teacher Jacqueline Daniels. "She’s extremely intelligent, respectful, she always comes to class and she gives 150 percent to everything she does."

Most teachers and students have a similar view of Kelli. She never got in trouble, never had any reason to go to the principal’s office. She was considered a good girl.

At least until this year.

Kelli Davis came out to her close friends and family two years ago, but she didn’t feel a need to advertise her sexuality. At school, she hung out with the same straight friends she’d had since childhood. ("Of course I had to assure them I was never attracted to one of them," she laughs.) Her older sister, Lindsey, accepted the news with ease. Her divorced parents were initially shocked, but they adjusted. And though her beloved grandmother often quizzes her about being a lesbian, she remains fiercely protective of her grandchild.

"I didn’t and still don’t understand what she’s going through," says Cindi Davis, a registered nurse. "But my job as Kelli’s mother is simply to love and support my child unconditionally, and I do." For her part, Kelli says her announcement wasn’t about advertising her status or seeking a relationship. It was about coming to terms with her identity. "I didn’t just choose one day to be a lesbian," she says. "That’s how I was born. My mom taught me my entire life to be honest and true to myself. I just couldn’t keep living the lie."

Kelli’s appearance, always modest, changed little. Like most teenagers, she dresses in jeans and T-shirts — though not the midriff-baring kind. Unlike most, she wears no makeup. This, coupled with her refusal to renounce her sexual identity, made her a target of some Fleming Island students. Starting several months into her junior year, she found herself a target of vicious namecalling and sexual slurs.

She pretended to ignore the abuse, but inside she ached. Sometimes, in the safety of her home, she sobbed uncontrollably, wondering how her schoolmates learned such cruelty. Mercifully, by the end of last school year, the slurs began to decrease. But in the fall, they would start again.

In September, accompanied by her mom, Kelli showed up at Cady & Cady studios in Mandarin to have her senior picture taken. The choice of outfit (provided by the studio) was either a black drape or a tuxedo top. As she stood watching the process, Kelli began to get an uncomfortable feeling. She watched as a girl with orange spiked hair and ear- and lip-piercings adjusted the drape low between her breasts, barely covering her nipples.

"I knew right then I couldn’t wear that drape. Even as a kid, I would never expose my chest," Kelli says with a slight smile. "So I choose the tuxedo. Hey, if it’s good enough for Sharon Stone and Sigourney Weaver, it was good enough for me."

When Kelli’s turn came, she donned the tuxedo top and bowtie, and posed for a series of photographs. The resulting shots are cute in a Mary Lou Retton-kind of way, but otherwise unremarkable.

Kelli herself forgot about them until October, when she began hearing rumors that her picture wasn’t going to appear in the yearbook.

Just how the story of the "tuxedo pictures" reached Principal Ward isn’t entirely clear. But accounts of his reaction are uniform. He was not happy. And he declared Kelli Davis’ picture would never be a part of his yearbook. Like everyone else, Kelli heard the news through the school gossip grapevine. She was shocked by the news, but her mother was furious. Cindi Davis, who calls her daughter "a good and caring person," says Ward’s reaction was preposterous. Her fiancé, Jacksonville neurosurgeon Scott Boggs, says Ward impugned "the dignity of one of his greatest students. I felt the tuxedo issue was benign ... a minor matter. He choose to escalate it to a major problem."

Boggs made an appointment in late October to speak with Ward and showed up with Kelli’s yearbook pictures in hand. Amazingly, Ward said he hadn’t seen the offending photographs. Boggs showed them to Ward, then asked the principal why he felt Kelli should not be part of the yearbook.

According to Boggs, Ward was congenial. He said that although he couldn’t talk with Boggs about the issue since he wasn’t Kelli’s legal guardian, he would "get back to" Cindi Davis with a solution, "possibly within the day."

A month passed with no word from Ward. In the meantime, the issue became a prime topic of conversation among teachers and students. Gossip spread throughout the classrooms, prompting some to offer Kelli words of support and others to launch fresh attacks. Girls stared at her meanly in the halls. Boys would mutter "dyke" as they passed. One senior boy stated loudly in class, "I hate queers."

As the abuse started anew, Kelli again entered that hellish place in high school where cruelty is the only currency and oblivion the only escape. Only this time, she had her own principal to thank for it.

Senior Kari Sewell is an adult in a teenager’s body. A bright, capable, no-nonsense young woman, her dream is to be a journalist and eventually publish her own magazine. Kari has been on the yearbook staff each year since she was in sixth grade, and last year was named editor of the FIHS yearbook for the second year in a row.

Kari began to visualize the 2005 yearbook more than a year ago. Since the Class of 2005 will be the first to graduate from Fleming Island High, she wanted the issue to be special — the best yearbook of her six-year career.

First-year teacher Sarah Kaneer, 21, is the faculty advisor to the yearbook. Since she’d never worked on one before, and had no knowledge of how it was produced, Kari, the resident expert, took charge of most production aspects.

"Several other girls worked very hard on the yearbook with me, but this was my baby," says Kari. "I conceived it, produced it and brought it to life."

Kari, a straight friend of Kelli’s, says when she first heard about the tuxedo ordeal, she was shocked and a little amused. "I thought it was quite comical that you can see a young lady’s derrière and cleavage around school, yet a tuxedo is not acceptable," she muses, noting the revealing fashions of her classmates. "In the real world, who would get the most attention?"

Kari’s sense of injustice was piqued. Being excluded from a high school yearbook for something so trifling seemed at best a lopsided response — and at worst a hysterical reaction. "[I] couldn’t understand what the big deal was."

Kari approached Sarah Kaneer and told her she disagreed with Principal Ward’s decision. She added she believed Kelli deserved a place in the yearbook and didn’t think the tuxedo flap should ruin her chances to appear in the publication.

But shortly before the mid-December Christmas vacation, Kaneer called Kari aside and told her the decision had been made that Kelli’s picture would not be in the yearbook. Having no say over the final production, Kari accepted the decision.

"I thought it was a done deal — over," says Kari. But when she returned from Christmas holidays on Jan. 3, Kari discovered it was not over. For nearly two weeks she was called to a series of meetings with the school guidance counselor, the assistant principal and Principal Sam Ward. The general consensus was that Kari somehow planned to put Kelli’s picture in the yearbook despite being told not to do so. Kari vehemently denied this, but neither her disavowals nor her track record were enough to save her job. Ward finally told her she was being removed from the yearbook staff because Kaneer "wanted [her] out of the class." Kaneer denies saying this, but Kari was removed. The Fleming Island Talon will be published without her, and despite the fact that she gave two years to the project, all traces of Kari Sewell as creator and editor will be stripped from its pages.

Kari says she was devastated by the news. "This is my future," she says. "It’s what I want to do with the rest of my life."

Kari insists she had no intention of undermining Ward’s decision. It would have been impossible to do so anyway. By the time Kari was yanked from the yearbook staff, the high school had already instructed Cady & Cady, Inc., the company that photographed the students and published the yearbook, not to permit Kelli Davis’ picture to appear.

Though Ward made his decision clear at school, he did not call Cindi Davis until late November. When he did call, he explained Kelli’s picture would not appear in the yearbook because it was not "uniform." Cindi Davis questioned Ward’s reasoning, but he was intractable. "He totally refused to consider anything else I had to say," she says.Cindi Davis responded that if he wouldn’t allow Kelli’s picture to appear with her class, she’d buy a full-page advertisement in the yearbook and run Kelli’s picture anyway. Ward implied he’d prevent the picture from running, even in a paid ad. Coincidentally, the deadline for yearbook ads fell on the day Ward called. But Davis hustled, bringing a check and Kelli’s picture to the school immediately.

She also called Clay County School Superintendent David Owens and asked him to intervene. A tall, thin man, seemingly uneasy in his own skin, Owens can often be seen with arms crossed or hands in his pockets, while he examines undetected particles in the air. Where Sam Ward has a reputation for being abrupt and unyielding, David Owens’ is the mirror opposite. Teachers, School Board employees and some parents of Clay County students call him "non-confrontational" and "conciliatory" to a fault.

"Whenever the buck can be passed," says one employee, "David Owens is up for the handoff."

The superintendent told Cindi Davis he had not seen Kelli’s picture, but declined to get involved. "Mr. Ward thinks the picture is not uniform," parroted Owens. "He has the final decision." Cindi Davis told Owens that she felt it was important for Kelli’s picture to be in the annual, so she was buying an advertisement in the back of the book. She said that since there would be paid advertisements for everything from car dealerships to tattoo parlors, they had better accept Kelli’s picture, too.

"Only if Mr. Ward OKs it," Owens stipulated.

When contacted by Folio Weekly in late November, Owens continued to back Ward. "I’m leaving it up the principal," he said. "I’m very much supportive of him."

"But," he quickly added, "you know why she wore that tuxedo, don’t you?"

Asked what he meant, Owens replied, "I can’t say." But he volunteered that Ward told him Kelli also wanted to wear the same color cap and gown as the boys at graduation. "You know why?" he asked breathlessly.

"Why?"

"I can’t say," he caged.

"What can’t you say?"

"I’m not saying!"

Owens’ hints about Kelli’s sexuality were frequent but closeted. Each time he was questioned about the insinuations, he declined to specify what he meant.

He couldn’t seem to bring himself to say the "L" word.

Asked about Owens’ suggestion that she intends to "disrupt" the graduation ceremony with a different-colored robe, Kelli says that’s a canard. "I have already ordered my robe," she assures, "and it’s the same color as the girls’."

The principal of Fleming Island High School is a king-sized man who sits behind a king-sized desk. He answers questions from somewhere inside this sense of regal purpose — long, windy responses that seem to measure the sound of his own voice more than audience response. Though he repeatedly yields to the incessant ring of a weather radio warning system (despite the clear November sky), he chides an interviewer for interrupting him.

"My father said it is rude to ask a question and not wait for the answer," he scolds.

Asked about the Kelli Davis controversy, Ward vacillates. Initially he explains that females in tuxedos are not in keeping with Fleming Island High School senior tradition. Reminded there is no such tradition since there has never before been a senior class, Ward is silent for a moment. Then he explains that senior class members voted to wear tuxedos and drapes, and their wishes should be respected. Pressed, he acknowledges that the entire class did not vote, only a few "representatives." He also admits the outfits were not identified as gender-specific.

"But female students wear drapes, and male students wear tuxedoes," he pronounces firmly.

Asked what he finds so objectionable about Kelli Davis’ photo, Ward insists he’s never seen it — a statement that contradicts the claims of Cindi Davis, Scott Boggs and several students and teachers. Even having not seen it, however, Ward says he is certain "it is not uniform."

Asked if he considers piercing, tattoos or orange hair uniform, he declines to answer. Asked what he would do if a student had religious objections to wearing a drape, Ward says the drape "could be adjusted" for religious purposes. Advised that there didn’t appear to be any school regulation that would allow him to declare Kelli’s photo unsuitable for the yearbook, Ward agrees. But he adds flatly that he makes the rules at Fleming Island High School. Then, although he’s spent most of the 40 minutes listening to the sound of his own voice and the squawk of the weather radio, Ward announces he has tired of questions. The interview is over.

After similar conversations with Ward, Scott Boggs and Cindi Davis decided to seek a more satisfactory form of communication with the Clay County school system. They hired Jacksonville civil rights attorney Bill Sheppard, who researched case law and the possibility of filing a lawsuit.

Unfortunately, though anti-discrimination laws have become tougher in the last few years, Sheppard felt that both the process and the outcome would be unsatisfactory to his clients. In a Dec. 15 letter to Boggs, Sheppard cited a 2002 decision, Youngblood v. School Board of Hillsborough County, Florida, in which a Florida high school girl objected to wearing a drape in her high school photo. Sheppard noted the case resulted in an opinion "unfavorable to our position." He also said that litigation would be long and arduous — and ultimately fruitless. Even if they won a lawsuit, it wouldn’t be resolved until long after Kelli’s senior year, and the goal of getting her picture placed with her class would no longer be obtainable. Sheppard was able to negotiate an agreement with the School Board’s attorney, however, that will allow Kelli’s senior picture to appear as part of a $350 ad in the back of the book.

Davis and Boggs have one last hope. With Kelli’s blessing, they plan to petition the Clay County School Board at its February 24 meeting to allow her picture to be placed in the FIHS yearbook.

Without support from the community, however, their plea may be moot. School Board member Carol Valencourt says that it’s David Owens’ policy "not to micromanage" the schools. He allows principals to make their own choices and decisions, regardless of their justifications.

"Unfortunately," offers Valencourt, "the First Amendment rights stop at the school gate."

Kelli Davis sits comfortably in an overstuffed floral chair, gazing into the distance. She talks about how hard she worked throughout her school career to make her dreams come true. Her face takes on a childlike sadness when she talks about her "senior quote," which is traditionally placed beneath the senior picture. She searched for just the right quotation for years and finally found one. It’s by German Nobel Prize-winning writer Hermann Hesse, who died in 1962: "If you hate a person, you hate something in him that is part of yourself. What isn’t part of ourselves doesn’t disturb us."

It’s a message for her classmates, and an expression of her belief that the abuse she suffered isn’t about her personally. But it is also an obvious dig at Principal Ward and the intolerance he represents.

"I’m willing to accept the negative aspects of this story if it helps others, because I’m not doing this for me," Kelli says. "I believe Mr. Ward is homophobic. He allows a lot of bad things to go on at the school, but he won’t let my picture be in the yearbook because he’s afraid of how other people will perceive his school." It’s this, as much as her own sense of outrage, that prompted Kelli to make her story public. "This is not the last time something like this is going to happen," she says. "Sooner or later Mr. Ward will have to realize that he can’t just manipulate students into denying their true identity to satisfy his own homophobia."